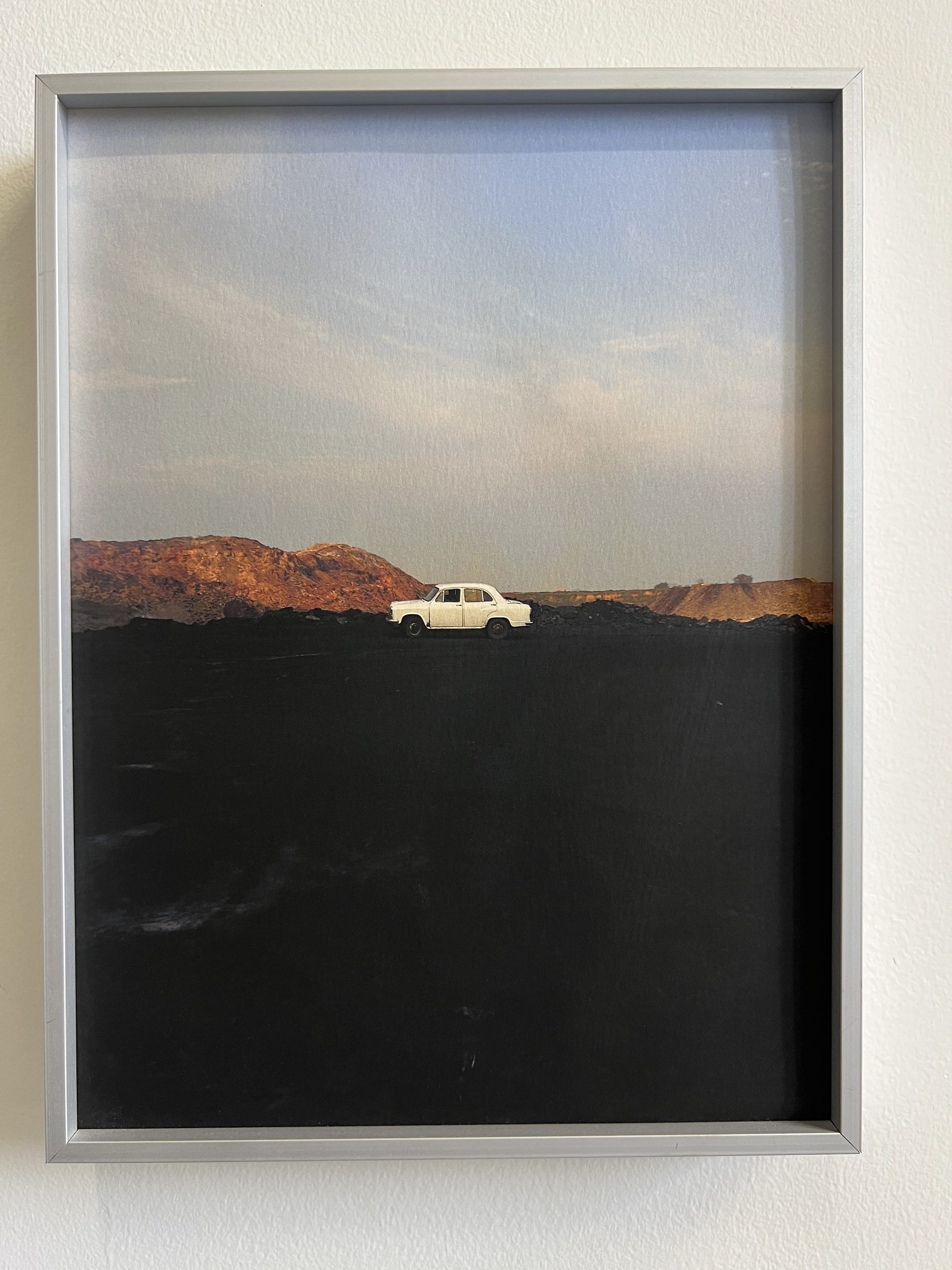

Bengaluru: For weeks now, students of environmental studies have been frequenting the Science Gallery in Bengaluru, where they gaze in wonder and awe at an exhibit on lithium mining. The exhibit explains the process of lithium mining in South America and its connection to electric vehicles.

They crane their necks to read the accompanying text, snap photos, and observe the miners depicted. Nearby, a full-screen animation illustrates the formation of carbon atom chains. It’s an all-you-need-to-know exhibit minus the ponderous classroom lecture.

The Science Gallery Bengaluru melds the history of science with art, making science accessible and buzz-worthy. Its presence befits a city synonymous with legacy scientific institutions and tech boom.

“We want to bring science back into the culture, as it is cultural. Science and society are not independent,” said Jahnavi Phalkey, the museum’s founding director. “We are trying to create a two-way bridge between research and the public by taking cutting-edge research, creating research festivals, building labs, and bringing in the public to witness and experience all of this,” she said.

The efforts are paying off. The museum has become a must-visit destination for families and students in the city.

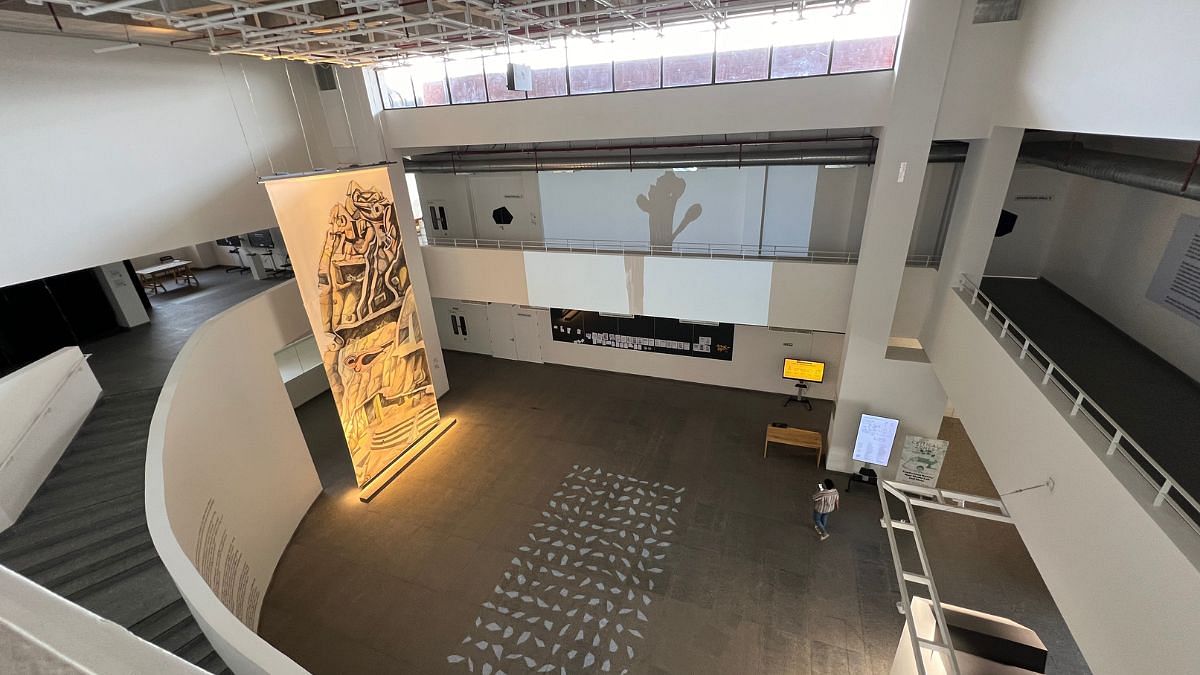

With its striking black and brick facade, inspired by the YSL Museum in Marrakesh, the Science Gallery Bengaluru boasts a sprawling white interior and steampunk ceilings, unlike anything seen in India.

“The intersection between art and science really stands out, and the archival and documentation is very detailed,” says Swathi Shivanand, a historian and faculty member at Manipal Academy of Higher Education (MAHE). “I wanted to introduce to students the various forms that climate communication can take, and the way artists come together to tell a climate story.”

Originally a mobile museum, the Science Gallery Bengaluru has now found a permanent home in Sanjay Nagar, welcoming visitors since January. With its striking black and brick facade, inspired by the YSL Museum in Marrakesh, it boasts a sprawling white interior and steampunk ceilings, unlike anything seen in India. As a government of Karnataka initiative, the SGB collaborates with top institutions such as the Indian Institute of Science (IISc), Bengaluru, the National Centre for Biological Sciences, and the Srishti Institute of Art, Design and Technology.

Even before its completion, the museum has attracted large numbers of enthusiastic students and curious passersby, drawn by its free entry; they walk out with a newfound appreciation for the wonders of the natural world, humanity’s past, and the earth’s precarious future.

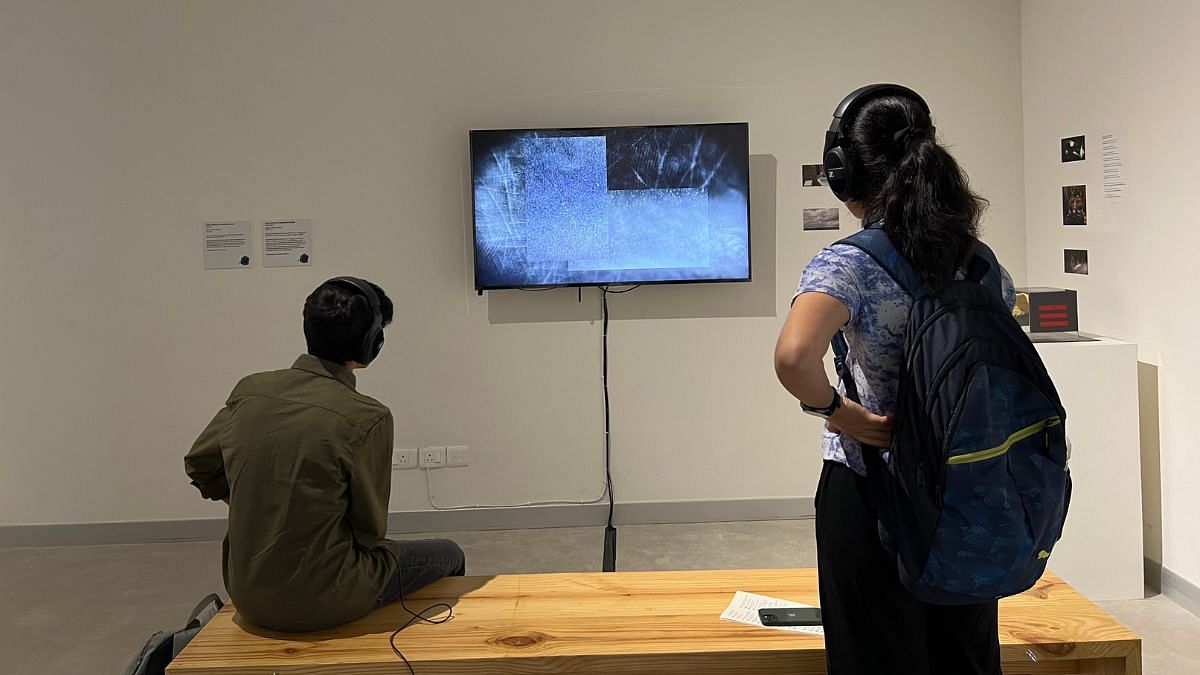

A floor above the lithium mining exhibit is a screen depicting what appears to be a dynamic video of an impressionist forest. With the accompanying VR headset, the scene transforms into a 360-degree view of millions of trackable floating dots —volatile organic compounds released by trees.

Further within, a quiet space enclosed by black walls offers respite from the bustling museum. Monitors display live streams of animals around the world, from penguins to snow leopards to endangered species. Throughout, young guides dressed in black lead visitors and student groups through these captivating displays and experiences.

At a time when humanity is facing several existential crises—pandemic, climate catastrophe, growing aspirations of millions—it becomes apparent that society and science are deeply intertwined

Rohini Nilekani, philanthropist and investor

“At a time when humanity is facing several existential crises—pandemic, climate catastrophe, growing aspirations of millions—it becomes apparent that society and science are deeply intertwined,” said philanthropist and investor Rohini Nilekani.

“There is a greater need to ensure that the ‘doing of science’ is not confined to institutions, public or private. Science should steadily become an inclusive pursuit. As an all-important bridge between science and society, Science Gallery Bengaluru is a pursuit in this direction,” she added.

Carbon meets art

The Science Gallery’s latest exhibit has everything to do with the theme of ‘Carbon’. Unlike traditional and even some modern museums, which are designed to encourage reading information while walking by the displays, the Gallery defies convention.

Architecturally, exhibits are not arranged linearly but dispersed throughout the building, clustered thematically rather than arranged in a linear fashion. Most exhibits are interactive, inviting visitors to engage through touch, action, or contemplation. For instance, ornate and colourful seating and wall cushions embroidered with the total number of each element’s atoms in our bodies offer a unique tactile experience.

Next to these, shelves display glass containers labelled after body parts, each containing ash to denote the amount of carbon present in our organs.

Behind them, Pranshi, nearly four years old, is engrossed in an arcade game called X-Carbon Universe, where she plays theoretical physicist S Chandrasekhar, capturing excess carbon from a star.

“These days, there is hardly any exposure to science, and I wanted to trigger some curiosity and fun in her,” says Shweta, her 38-year-old mother and a clinical medical advisor to a pharmaceutical company.

Wandering through the exhibition halls, visitors stumble onto various nooks and enclosed, thematically lit spaces housing diverse displays. These exhibits combine physical objects, touchable screens, videos, interactive experiments, drawings, books, and projector displays of colourful diatoms or algae. Notable displays include petri dishes containing microbial growth cultures from India’s mangroves and live silkworms munching away at carbon nanotube-reinforced mulberry leaves to produce nanotube-reinforced silk. A week later, they were all in cocoons.

One exhibit that captivates Vaishali Upadhyay (24), a fellow at the India Institute of Human Settlements, features black and white artwork made from carbon black particles. They were collected from masks worn by French visual artist Anaïs Tondeur during her travels across Bengaluru. These particles became the ink that drew Bengaluru’s skies, with black particles corresponding to actual particles that were tracked by her camera and captured by her mask. Mapping the data to atmospheric emission data from scientists, she creates charcoal-like artwork of the skies of the city, with darker shades corresponding to higher emissions.

“I never thought carbon and art could come together this way. I thought it was an inspiring and extremely powerful way to depict carbon footprint,” said Upadhyay.

The atrium, walkable areas, and stairways of the building are adorned with unconventional art pieces. A large surrealist artwork by Pune-based artist Prabhakar Pachupate welcomes visitors at the entrance. It’s a cross-section of a mine alongside its tragic human cost and work opportunities, in layers of earthy tones.

At another part of the museum, Yooti Bhansali (39) from Mumbai is intrigued by the ‘Mycoblock Chair’. It’s a chimaera of a chair, made from plastic and Reishi mycelium fungus, multiplying on a ragi straw. A reminder to visitors of the wasteful nature of plastic consumption, the chair looks like it stopped metamorphosing midway.

“It makes the familiar and mundane look like something out of a movie shoot. It immediately prompts people to investigate. Most exhibits in most museums need guides or explanatory text, but this one is just there. It’s the pièce de résistance of the exhibit,” Bhansali says.

One particularly striking exhibit near a winding staircase casts shadows resembling wilting stamen. In reality, it’s a projection of high-exposure silhouettes of burning matchsticks, illustrating the hidden dangers of carbon fumes in our homes, explained Jahnavi Phalkey, the founding director of SGB.

Building a community space

Phalke’s office faces the largest tree among a smattering of plants on the newly constructed premises. Like the art on display inside, it’s not decorative but ecologically appropriate and consistent with the region. The main goal of the landscape is to offset the heat from the concrete and enable drainage with rain trees.

Phalkey wants to explore open courseware, publish activity handbooks, and collaborate with educational and scientific centres in Karnataka to create content in English and Kannada. But first, she must find the suitable rain trees for the SGB campus, which is bearing the brunt of Bengaluru’s new upper-30s heat beneath its black-and-brick exterior.

We have a near-equal distribution of experimental and exhibition spaces. It’s a pioneering idea we’re trying out here. None of our sister galleries abroad have a lab complex like this, neither do traditional science centres and museums

—Jahnavi Phalkey, founding director of Science Gallery Bengaluru

Phalkey has yet to process the success of the permanent gallery. She is fresh off winning the Infosys Science Award and is currently overseeing the next phase of the SGB building construction.

When finished, the entire gallery will become a community space. The building will be lost within the greenery with plenty of space for activities, workshops, brainstorming, co-working, and in Phalkey’s words, just “hanging out”. It will embody the words inscribed on the exterior wall: Science, Culture, Experiment.

And that is the motto the gallery wants to live by, explained Phalkey. The result? Only temporary exhibits.

“We also have a near-equal distribution of experimental and exhibition spaces. It’s a pioneering idea we’re trying out here. None of our sister galleries abroad have a lab complex like this, neither do traditional science centres and museums,” said Phalkey.

The spaces might be fixed but there are no permanent exhibits. It is conceived as a fluid space that encourages visitors to embrace change. Once the current exhibition ‘Carbon’ concludes and the next one takes its place, the building’s appearance will drastically change. Same interiors, but not a single familiar space. Both the exterior and the interior are purposefully designed to be fluid, diverging from traditional museums.

The building contains multiple developing lab complexes, which will be experimental spaces for research. The nature lab currently hosts a tissue culture room and a microscopy room. The materials lab has a workshop attached to it. There are labs for new media, humanities, theory and study, and a dark room in various stages of completion. By the end of this year, there will also be a food lab that is attached to an indoor-outdoor cafe.

The SGB has three exhibition halls — an open studio, a reading room, and an activity hall. There are also open spaces for lectures, movie screenings, workshops, and other kinds of group activities aimed at connecting the public with scientific research. Some spaces are just for reading, working, or even playing board games.

The gallery has done a very good job of bringing together science and art. Students have typically studied several of these basic topics in class, and here, they get a nuanced understanding of how science could be subjective depending on perception

—Venkat Ramanujam, environmental anthropology postdoctoral

A central attraction and a third space will be the upcoming cafe. A part of the food lab complex, the area designated for the cafe will include large transplanted and existing trees under whose shade people of various culinary tastes will consume experimental food or regular snacks, while maybe performing their own food chemistry experiments.

“The gallery has done a very good job of bringing together science and art. Students have typically studied several of these basic topics in class, and here, they get a nuanced understanding of how science could be subjective depending on perception,” said environmental anthropology postdoctoral Venkat Ramanujam from Bengaluru’s Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment, talking about students’ interest in science, mining, human rights issues, and their intersection with artistic depictions. As visiting faculty at MAHE, he has brought 80 college students to SGB.

Many of the exhibits demand the viewer’s attention and concentration to make sense of the underlying message. Architect Sneha Chhabria (33) who visited the SGB recently found some of the displays slightly hard to understand, especially for those without a science background.

“But the visuals help. The Aerocene was easy to understand and will also be something I will be looking up when I go home,” she says, referring to an exhibit titled Aerocene Pacha from the MIT Earth Sciences department. There are images and clippings of a fuel-free hot air balloon that flies using energy from the sun as the heat radiating from the ground.

For those who still need help, there is a team of ‘mediators’ who act as guides, and are trained intensively for a month in public engagement, science communication, the science of the exhibits, and understanding of the art.

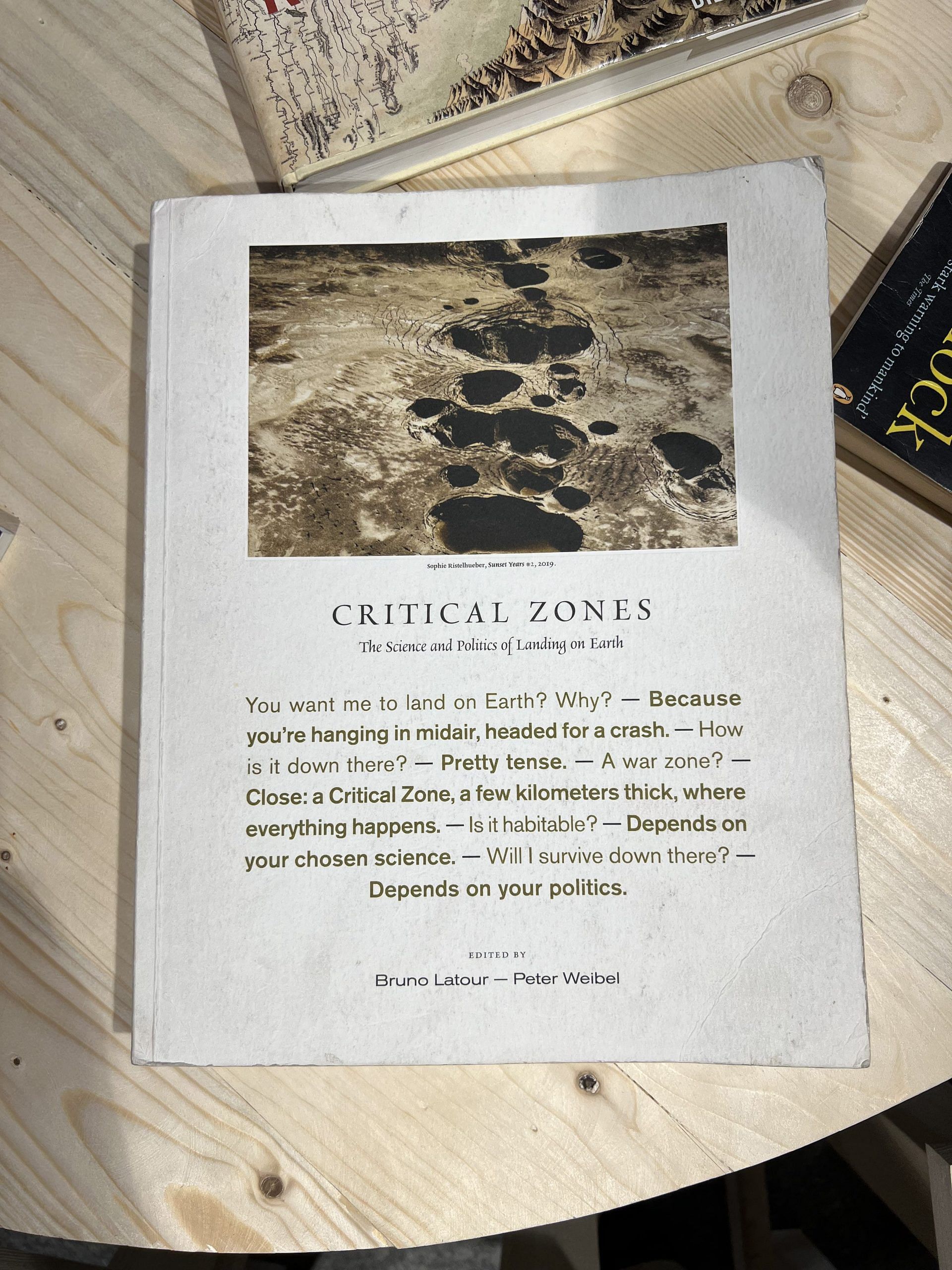

Critical zones and future

A white badge in her all black uniform—a shirt and a pair of trousers—identifies Teresa Fernandez (23) as a mediator. A biotechnology graduate, Fernandez is steeped in the world of science, but the gallery is a revelation.

As a mediator, she is trained intensively to initiate interesting discussions and questions, for deep public engagement, and has workshopped with artists and scientists to understand the work she is to explain and get people to think about.

“Occasionally, I will see a previous visitor come again with their friends and family, and explain the same concept to them. It feels great to see that the exhibition had an impact in stoking scientific curiosity,” says Fernandez, who has been assigned to the Critical Zones exhibit that the SGB was hosting until last week.

At its entrance is an eye-catching 1845 illustration of biogeology by German cartographer Heinrich Berghaus showing organisms and geological features in horizontal chronological order.

The temporary travelling exhibition ‘Critical Zones’ was a collaboration between the Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe, Germany, and Goethe Institut, Mumbai. It explored the miniscule kilometres-thick layer of the planet’s crust and atmosphere within which life resides.

To transform this sensitive biosphere, climate science is becoming increasingly interdisciplinary, and the combining of plants, rocks, weather, microorganisms, marine life, and more, is depicted here in a form of exposition art and interactive displays.

For mediator Tushar Sharma (22) who has a bachelor’s degree in Physics and minored in climate science, this is a learning experience as well. He’s on a month-long internship, and especially enjoys explaining what he studied with interactive experiences to curious children.

Even the naysayers are drawn to the gallery.

“I have had never-ending conversations with climate change deniers, who have come with notes full of conspiracy theories,” he laughs. In another corner, his colleague helps fit and tighten a virtual reality headset on a young girl aged 11 or 12, and later her grandfather, while explaining the science to them. It takes her on the path to discovery of volatile organic compounds emitted by trees in a forest.

A cosmos of network to take science beyond

It’s fitting that the SGB is in Bengaluru—where some of the best research and science institutes in the world rub shoulders with ISRO, multinational IT companies, startups and philanthropic foundations.

The Gallery, which is not-for-profit, is a part of a worldwide network of Science Galleries located in eight cities around the world including Dublin, Atlanta, Melbourne, Berlin, and more. The first in Asia, it is also markedly different from the international ones, which are all affiliated with universities. Instead, Bengaluru’s independent project and building is funded by the Government of Karnataka, who is the founding partner, and India’s familiar science and tech investors who sit on its board, led by Kiran Mazumdar Shaw.

“The mission of the Science Gallery is to take science beyond their hallowed gates and out onto the streets, mingling with the citizens, instilling in them pride for the city and curiosity about scientific research and experimentation, and its importance in our lives,” says Nilekani. The aim is to demystify science, strip it off its power to intimidate. “The museum will grow into a hub where individuals from all walks of life come together to have cultural conversations around science.”

As executive director, Phalkey works with a team of multicultural and interdisciplinary experts who decide the topics and themes for upcoming exhibits. The curation process takes at least a year, and the outcome will be hosted by her team of roughly 25 staff and 30 mediators.

Previous exhibitions have included the pre-pandemic ‘Elements’ and ‘Submerge’, and the hybrid Phytopia, Contagion, and Psyche, which were held at various locations around Bengaluru before the new building was inaugurated with ‘Carbon’.

SGB has put out a call out already for experiments, art, and displays that can be a part of the upcoming exhibit, ‘Quantum’, about the world of small things, set to go live June of next year. Mediators and apprentices will be trained once again, and with the purpose to think beyond disciplines, said Phalkey.

The transient and experimental nature of the gallery is incredibly important for Phalkey and her team. It’s a reflection of how science and technology is rapidly evolving.

“And we need that agility to maintain the institution. The minute we settle, we fossilise and become irrelevant,” says Phalkey.

(Edited by Prashant)