Delhi/Morigaon: In the little-known village of Chikabori in Assam’s Morigaon district, around 80 teenage boys and girls are practising their spikes, blocks, and serves. They do not have proper shoes or knee and elbow pads, but they don’t mind the occasional bruise. Their focus is on the ball. It’s not cricket, football, or basketball that’s captured their attention—but volleyball.

The sport has taken over Chikabori and other villages and towns across Assam thanks to a homegrown initiative called the Brahmaputra Volleyball League (BVL). And it’s all because of 44-year-old Abhijit Bhattacharya, a former Indian volleyball captain from Assam who represented the country between 1995-2005 in over a hundred matches.

Bhattacharya is channelling Assam’s love for the game through BVL and turning the league into a vehicle for a quiet revolution in Assam. Since he launched the initiative in 2019, the ‘movement’ has gathered force, rallying thousands of children across 160 BVL training centres, along with coaches, instructors, and volunteers.

“We said, come out of your house to play a sport. And let that sport be volleyball. But at least come out of your house,” said Bhattacharya who juggles his 9-5 job with ONGC at its New Delhi office along with spearheading the biggest homegrown sporting movement in Assam.

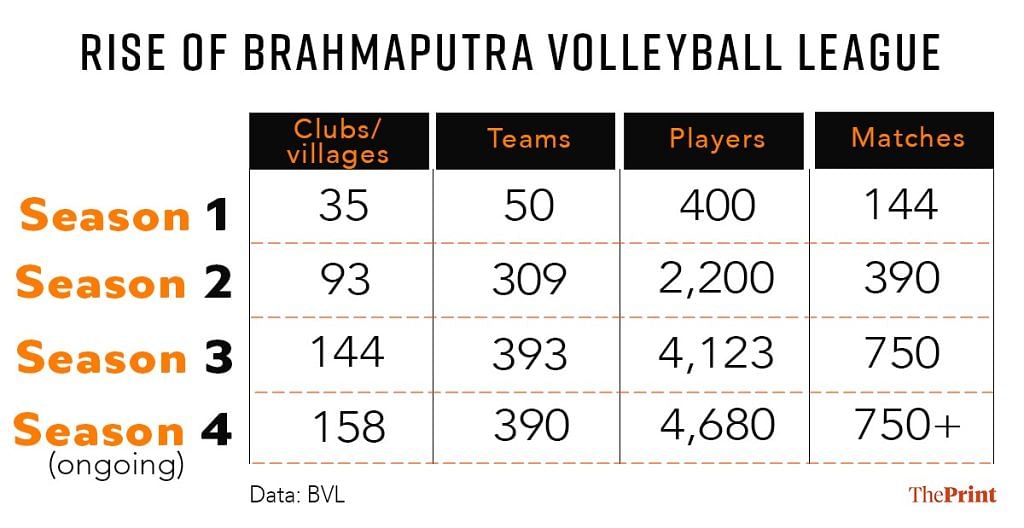

When the fourth season of BVL kicked off this year in October, there were 390 teams from 158 villages. The number had ballooned from 50 teams from 35 villages that participated in the first edition of the league. Yet, these figures are just a fraction, representing only the league players. Outside the tournament, more than 10,000 kids sweat it out every day at the BVL centres.

There are no fancy indoor stadiums with synthetic courts and bright lights as seen in televised volleyball games. The BVL training centres are makeshift courts carved out on a community field or someone’s backyard or farmland. But the intensity with which the sport is played matches professional tournaments.

“Volleyball is popular in our village. But we remained deprived of facilities. Only when BVL approached us, we could start this centre,” said Ranjit Das, 34, a resident of Chikabori.

He’s in charge of the Pragati Volleyball Coaching Centre, which has two rectangular courts next to a naamghar (prayer house) and is supported by BVL. This year, 36 of Pragati’s players are part of the Brahmaputra Volleyball League-4 and are now in the finals in the state sporting event, Khel Maharan, representing Morigaon district.

All of this is unfolding organically, untouched by corporate management and devoid of flashy marketing. Volleyball in Assam is not merely a sport—it’s instigating profound social and cultural change across the state’s rural landscape.

For just a nominal amount of Rs 14,000, anyone can own a team, with the sum contributing to player kits, travel, and miscellaneous expenses.

Also Read: Neeraj Chopra is sharpening his javelin for Paris. He has to prove Tokyo was no lucky toss

100 balls, 100 players, 100 training centres

More than 150 kilometres from Morigaon, another village in Darrang district, Hazaripaka, kicked off December with a bang. This unassuming village received a visit from none other than Brazil’s Giba, an Olympic gold medallist and a living legend in the volleyball world.

Instead of flashing cameras and suited dignitaries, the occasion hummed with a different kind of energy—the presence of three volleyball greats. Apart from Giba, two other Olympic gold medallists, Cuba’s Mireya Luis and Serbia’s Vladimir Grbic, headlined the event as part of a knowledge-transfer programme between the Federation Internationale de Volleyball (FIVB) and BVL, all organised by Bhattacharya.

Although he was away from Assam for 10-12 years while playing for India’s national team, Bhattacharya never lost touch with his home state.

“When I retired from active sports, I went there (Assam) in 2008-09. That’s how my association with the community and volleyball promotion started,” he said.

Even before retirement, during a casual visit to his home in Tezpur, he heard about the popularity of volleyball in a village in his district. He was so moved by the passion for the game among youngsters that he extended his leave to organise a grassroots-level tournament with eight participating teams.

This league is a platform where, if you have talent, you can bring a team and showcase it

Abhijit Bhattacharya, BVL founder

“In the evening, when one of the teams started winning, the people of that village started gathering around the players to cheer them on. They found something to do. That was the beginning,” said Bhattacharya.

He realised the situation was “the same everywhere”. Soon, he, along with a few former players, started an academy and scouted for quality players. However, for a decade, their efforts remained confined to Sonitpur district.

The seeds for BVL were sown in 2018 when Bhattacharya, together with former Assam players, launched a project called Assam Volleyball Mission 100.

The goal was startlingly simple: give a hundred balls to children. From there, it expanded to finding 100 new volleyball players and then to establishing 100 training centres.

In the initial days, they lacked funds and a clear direction. Bhattacharya recalls his friends asking him to join the state’s volleyball association and take over as its secretary or president to initiate change. But he stuck to his guns.

“I was never comfortable taking those positions. I said, if you want to support volleyball, let’s start from something very basic and small—the ball,” he recounted.

This approach, coupled with the sport’s affordability and popularity, gave a jump-start to the movement’s organic growth.

Bhattacharya’s vision for BVL extends beyond the court. He’s also using the platform to drive positive social change. He tackles sensitive topics head-on, including menstrual hygiene.

Wide network, deep bonds

Bhattacharya isn’t just passionate about volleyball, he’s a master storyteller. His inspiring narratives on Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, LinkedIn, and even during personal presentations have helped gather both supporters and sponsors.

Stories like villagers crafting bamboo tripods to broadcast matches, women entrepreneurs opening BVL centres after marriage, and his personal tale of teaching volleyball to kids through Zoom during the pandemic— these are what bring in sponsorships and keep the league running.

A single LinkedIn post landed Signify (formerly Philips Lighting) as BVL’s light sponsor. And in March, a 15-minute meeting slot with FIVB officials turned into a 1.5-hour discussion, eventually leading to the visit of the three Olympic legends to Assam.

When you visit villages, when you see the small kids play with so much perfection, it is heartwarming. It’s such a great movement

-Shailesh Sharma, owner of a BVL team

Over the years, he’s rallied an impressive band of contributors to the cause, from badminton icon Aparna Popat and Prime Volleyball League CEO Joy Bhattacharjya, to Assamese communities in Singapore, the US, and the Middle East. For just a nominal amount of Rs 14,000, anyone can own a team, with the sum contributing to player kits, travel, and miscellaneous expenses.

There’s even a BVL website, although Bhattacharya says it isn’t operational currently—lack of time, he sighs.

That’s because the father-of-two and office worker does everything himself. “There is no social media team, no digital team. I designed the banner and made the videos. I do everything on my mobile,” he said with a smile.

When the three Olympians visited three villages and trained coaches, Bhattacharya handled all the logistical details.

His whirlwind schedule continues. Back in Delhi, at the ONGC office cafeteria in early December, he was on a call with PhonePe CEO Sameer Nigam. One of the topics of discussion: getting a jersey for Nigam for a volleyball match the next day in Mumbai. This match featured the Mumbai Meteors—a Prime Volleyball League team acquired by PhonePe’s Nigam and Rahul Chari; Bhattacharya is the team’s mentor.

Bhattacharya’s connections run deep and wide and BVL is racking up admirers at a remarkable rate.

“When you visit villages, when you see the small kids play with so much perfection, it is heartwarming. It’s such a great movement,” said Shailesh Sharma, president of the All-Assam Private School Association and the owner of a BVL team.

Bhattacharya credits word-of-mouth and social media for BVL’s success. But this has come with its own challenges. He says that until season 2, he knew all the owners of the team personally. “Now it has gone so big, I have lost all control. I need a team to coordinate all this, which I don’t have!”

It takes a village

In Chikabori village, the Pragati Volleyball Coaching Centre got off the ground with only one coach, a ball, and a net two years ago. But it wasn’t a solo effort— the entire village banded together.

Volleyball always had a special place in the villagers’ hearts, so when coach Rahul Kumar Nath, 31, approached them on behalf of BVL, they immediately threw themselves into the task. The men fenced the court and the women created a 10-metre-long volleyball net overnight.

“Rahul Sir got us the material and we knitted it,” said 28-year-old Udesna Das, field in-charge at the centre.

BVL recently provided ten floodlights, but setting up the center was a community affair—no special technicians were hired, and the villagers did everything themselves. Last month, they came together to raise bamboo poles to fix the floodlights. And when the children play, the village elders are designated as field in-charges, keeping track of time and cheering on the players.

“The support of villagers has been phenomenal. Now, we have three courts in Chikabori and adjoining villages. During the monsoon, it gets a little difficult— but it’s heartening to watch the children waiting for the sun to dry up the field,” said Nath, who lives 15 kilometres away in Nuagaon village.

After practising for a year, we have got the chance to play at the district level

-Biswajit Basumatary, Chikabori resident

Volleyball fever burns bright here. Each of the 150-odd households in the village has a child or two playing the sport. The centre trains not just school students, but young men and women who hope to make it to the district and national level.

“We have played volleyball since childhood. Since we met Rahul sir and started training under him, we have gained great insights into the game. After practising for a year, we have got the chance to play at the district level,” said 23-year-old Biswajit Basumatary. He and his friend Bishnu Ram Patar, 19, cycle more than 20 kilometres every day from adjoining Kustoli village to play volleyball at Chikabori.

“After college, we come here for practice. Before we start playing, we train the younger ones for a few hours,” says Jintu Das (20) who practises with friends for six hours from 2pm to 8pm.

In March this year, they got the opportunity to meet four players from the Netherlands who visited Chikabori with Bhattacharya.

“The children used to play volleyball even before the centre was set up, but took more interest since the BVL coaching centre was established. Our children are talented, but the government hasn’t paid as much interest as it should have,” said another resident, Mukuta Bordoloi, 42.

Not just a sporting revolution

Bhattacharya’s vision for BVL extends beyond the court. He’s also using the platform to drive positive social change. He tackles sensitive topics head-on, like menstrual hygiene, encouraging open dialogue and breaking down stigmas.

“Whenever we have funds, we try to give sanitary napkins to girls playing in the U-16 division,” he said. However, in the rural countryside of Assam, distributing sanitary pads at a sports centre, usually run by a male in-charge, is a multilayered issue.

“It’s a big challenge to talk about it (menstruation) in the open, to distribute sanitary pads,” he added. “People feel shy. I wanted them to speak up. Because these are girls coming to play, they should feel free to talk to their coach about it.”

BVL’s training centres are driven by passion, not paperwork. Bhattacharya doesn’t insist on a training certificate for the in-charge, who doubles up as the coach.

Bhattacharya recounted an incident where a centre in-charge complained when someone posted pictures on WhatsApp of sanitary pads being distributed. The in-charge groused that it wasn’t appropriate to do this in the open.

“I intervened, saying this is how you should do it. You should give openly, talk openly. Then, girls will open up. It’s not a taboo,” Bhattacharya said.

In another instance, someone raised concerns about updating players’ information online, claiming that some Muslim families didn’t have mobile phones. This bothered Bhattacharya. “I replied, ‘You might not have a mobile, that’s fine. But you don’t have to say that it’s not available to the Muslim community. Stop at that’.”

Also Read: Deogarh dreams of next hockey star. No turf, no shoes but ‘every house has a player & fan’

For the people, by the people

BVL’s training centres are driven by passion, not paperwork. Bhattacharya doesn’t insist on a training certificate for the in-charge, who doubles up as the coach. Anyone with a genuine love for volleyball and a commitment to seek out new talent can start a centre, fostering a sense of community ownership and responsibility. Children are not charged any fees.

“When they come, they talk about their centre with a sense of ownership,” Bhattacharya said. “This league is a platform where, if you have talent, you can bring a team and showcase it.”

Last season, 740 matches took place during six months. Bhattacharya made the game chart on a large Excel sheet sitting in Delhi. He doesn’t need to micromanage the tournament. Everything happens in auto-mode. “The community takes the ownership of deciding matches; we don’t decide the match day. It’s a decentralised way of doing things,” he said.

Satrajit Chutia from Dibrugarh district was so moved by his experience as a referee for a league tournament in Season 2 that he decided to start a centre in his village, Langerie.

“I always had a dream of taking the children of my village forward,” said the 33-year-old school teacher. The centre now nurtures more than 80 young players—36 girls and 47 boys. In their debut season, his three teams reached the prestigious Super League stage.

“Before BVL, we didn’t have a platform to take forward the sport. There would be two or three men’s volleyball matches but nothing was happening for women. Now, young kids are getting so much attention and a solid foundation for the future,” he said.

Last year, Bhattacharya visited the centre— which Chutia terms “an unforgettable day”.

“We were so encouraged that the former captain of the Indian team came to visit us,” he recalled.

The schoolteacher acknowledges that not every child at his centre, run on family land, will become a star player. But, for this homegrown volleyball team, victory is not merely measured by trophies.