Kochi: He has been captured twice, translocated twice, and tranquilised multiple times — all in less than two months. He has been playing truant between Kerala and Tamil Nadu. And somewhere along his journey, he became a symbol of state pride for Malayalis. He has fan clubs on social media. There’s talk of making a movie about his life. And every video of him — whether napping, eating, or lolling in grasslands — goes viral.

This is the 36-year-old elephant Arikomban’s curious, chaotic and charismatic story so far.

What started as innocent rice raids in local villages turned into rumour-mongering when stories began to spread of his alleged violence, setting forest officials on his tail. His subsequent journey crisscrossed between Kerala and Tamil Nadu, with both states’ forest departments hot on his heels.

Arikomban’s story has struck a chord with hundreds of people, inspiring fear and fame in equal measure. While the hapless residents of villages like Tamil Nadu’s Cumbum might have been too afraid to venture out of their homes, Arikomban’s fans in Idukki have erected statues in his honour. Impassioned petitions are being signed, addressed to the central government asking for the elephant to be saved.

“Arikomban has captured national attention — it’s actually good because it brings the conversation [around human-wildlife conflict] to the mainstream, but unfortunate because it becomes a fight for this one elephant,” said Sumanth Bindumadhav, director of Wildlife Protection at the Humane Society International India. “They get more attention when they’re anthropomorphised.”

But the jury is still out on how human-wildlife conflicts like Arikomban’s case should be handled. And the question of whom he belongs to, or whose “problem” he is — Kerala, Tamil Nadu, or the forests between the two states — still looms large.

“Arikomban is a typical example of how human-animal conflicts arise,” said Jayachandran, secretary of the Idukki Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (SPCA).

Idukki is Arikomban’s old stomping ground and was his home until his translocation. But, significantly, Arikomban’s story has also prompted a change in mindset, according to Jayachandran. “Earlier, the response to Arikomban was to capture him and put him in captivity. Now, after following his story, more people think that he should live in his own habitat.”

Also read: Elephant or wild pig, none should die in blast. Cuteness quotient must not guide conservation

Arikomban’s story

Arikomban was well-known in Idukki’s Chinnakanal even before he made headlines in March 2023.

The elephant was orphaned at one-and-a-half years old in the cardamom estates of Idukki. His mother had an injured leg and was being taken care of by the tribal community and forest officials for three months until she died. He was separated from the herd and grew up in relative isolation — thus developing his habit of raiding villages for rice. His name is portmanteau of the Malayalam words for rice (Ari) and tusker (komban). Arikomban regularly visited the site of his mother’s cremation, according to local residents.

But over the last few months, the elephant has earned a more insidious reputation as a “troublemaker,” something that the local communities refute.

The roots of this reputation stem from 2002, according to Jayachandran. The AK Antony-led Kerala government handed out land deeds to 301 landless tribal families in Chinnakanal, forming the 301 Colony — despite a report from the Divisional Forest Office of Munnar stating that the land was not suitable for human settlement because it’s an elephant habitat.

The informal settlements and huts were far and few beyond, which allowed elephants like Arikomban to roam freely without damaging homes. The 301 concrete houses were densely packed in the elephant corridor which meant that the movement of elephants led to some of these houses breaking.

Most families eventually left the 301 Colony, and only around thirty individuals still live there, according to Jayachandran. A committee constituted by the Kerala government in 2009 suggested that the Chinnakanal region should be declared an elephant park and that residents should be resettled to avoid human-wildlife conflict.

This process was never completed.

Jayachandran alleges that the rumours of Arikomban becoming violent and killing Chinnakanal residents — of which there is no proof — were started by the land-grabbing and resort mafia. Earlier this year, the clamour for Arikomban’s capture reached a crescendo, and the forest department announced its plan to keep the elephant in captivity.

Animal rights activists and wildlife conservationists filed pleas in court, saying that there was no proof, up until then, that Arikomban had physically harmed anybody, especially since local tribal communities had been living in harmony with him for decades. In April, a court-appointed committee decided that translocation would be a better way forward.

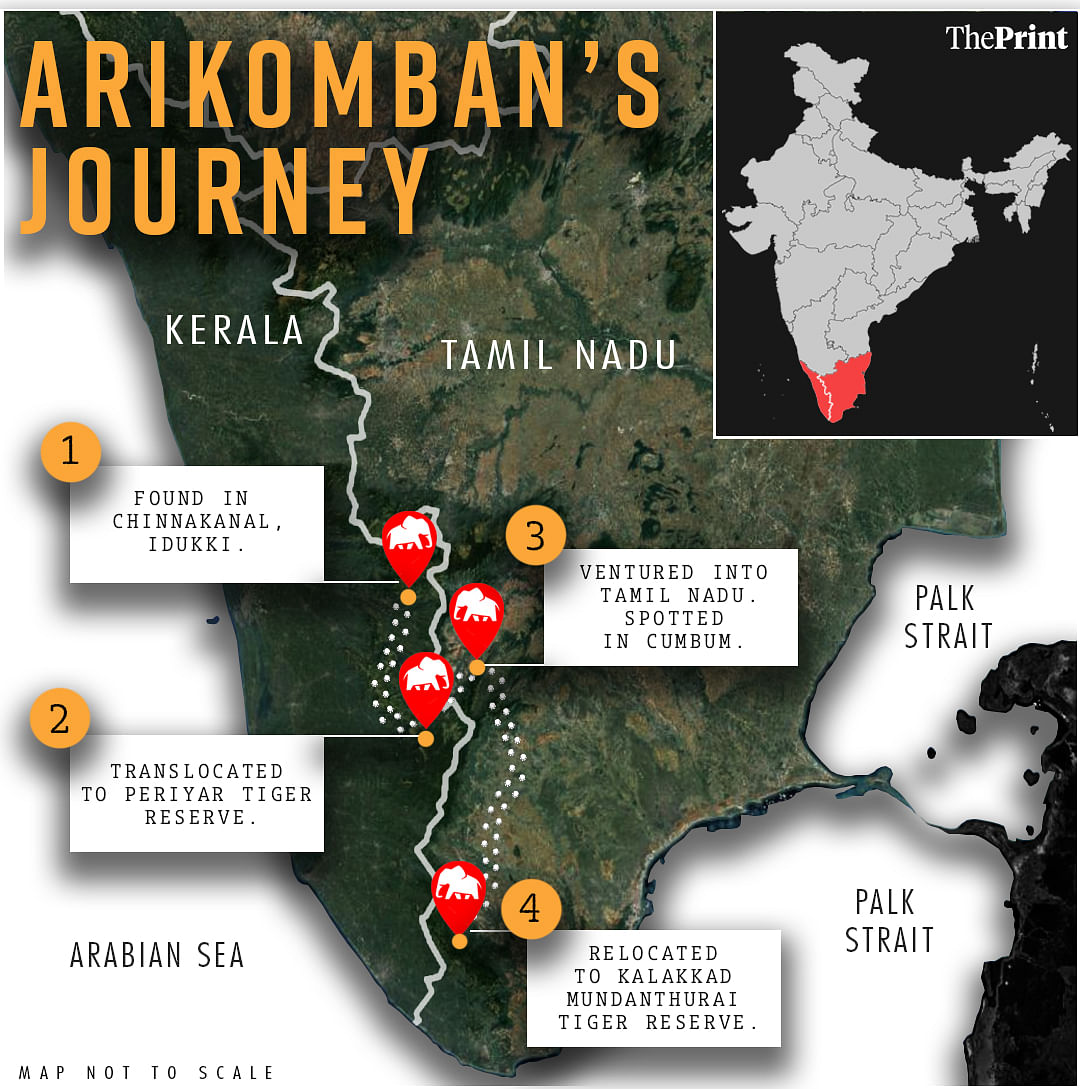

A two-day operation with 150 officials commenced. On 29 April, Arikomban was translocated to the Periyar Tiger Reserve, 80km away from where he grew up.

But the tusker had other plans.

He was on the move and ended up crossing the border to Tamil Nadu. Almost exactly a month later, on 27 May, the residents of Cumbum were in for a shock: Arikomban went on a rampage through the town, damaging structures. A curfew was declared when three people were injured, and a 65-year-old man died of his wounds on 29 May.

Now, it was Tamil Nadu’s turn to translocate the elephant. On 5 June, Tamil Nadu’s forest department tranquillised and captured the elephant, moving it over 200km from Cumbum to the Kalakkad Mundanthurai Tiger Reserve — Arikomban’s new home.

The forest departments of both Kerala and Tamil Nadu did their best when it came to Arikomban, said Supriya Sahu, Additional Chief Secretary to Government, Department of Environment, Climate Change and Forests. His new home, said Sahu, is pristine forests with rolling grasslands, plenty of water, and minimal human interference.

“It’s only been about two weeks since Arikomban was translocated, so it’s too short a time to say he’s settled. But we can definitely say that we are monitoring him, and that he’s doing well and that he’s comfortable,” she said.

Also read: When it comes to monkeys, Ayodhya model will succeed where Delhi failed

The issues with translocation

Along the way, Arikomban has found himself embroiled in legal battles and in larger conversations on the ethics of translocation.

The elephant’s time in Cumbum raised alarms for several — a businessman filed a petition in the Kerala High Court alleging neglect by the Tamil Nadu state authorities and asking for Arikomban to be brought back to the state, another petition filed in the Madras High Court also asked for his relocation to Kerala.

Translocation is often seen as a cruel practice forcing an animal to unfamiliar territory — much of the conversation around Arikomban is about how he was simply trying to make his way back to Kerala from Tamil Nadu when the incident happened in Cumbum. But the flipside to this argument is that Arikomban himself ventured across state borders when he was translocated the first time, according to Jayachandran.

Kerala’s forest minister AK Saseendran took the opportunity to lambast “elephant lovers” and animal activists for the panic over how to handle Arikomban. He said petitions by these activists are the reason he was moved to the tiger reserve near the border and not the Kodanad elephant sanctuary in central Kerala.

“This issue is a huge pandora’s box,” said researcher-conservationist Tarsh Thekaekara, trustee at the Shola Trust, a nonprofit involved in conservation in the Nilgiris. “There are no laws on the governing of animals outside protected areas, and so there’s a huge blackhole and lack of policy when it comes to this.”

Thekaekara said that at a recent meeting of 14 experts on the issues of translocation organised by the Coexistence Consortium, there was a near consensus that translocation is the best way to deal with cases of animals becoming violent or destructive towards humans particularly in urban spaces. But ultimately, if an animal doesn’t settle down in natural habitat and returns to urban areas, captivity may be the only solution. Continuously sedating and translocating animals could in some cases be more traumatic than the process of training for captivity in forest camps, especially if the human death toll continues to rise, making people less tolerant of elephants everywhere.

“You don’t need to capture every elephant because it’s out of place — every elephant has different behaviours and needs. There are elephants who become so habituated that they don’t attack humans, and live in coexistence.”

– Tarsh Thekaekara, conservationist

Thekaekara said that keeping elephants in captivity is a huge expenditure for state governments, so translocating them and keeping them in the wild is a preferred option. While elephant numbers are arguably going up, according to him, the real issue is maintaining a healthy habitat while planting non palatable crops along forest edges. Forest habitats are being degraded, forcing elephants to venture out in pursuit of food.

He pointed to the optimal foraging theory, a model of behavioural ecology that helps predict animals’ feeding patterns. The theory suggests that instead of spending long hours a day feeding on crops that are not suited to them, elephants would rather travel a longer distance to crop-raid and feed for fewer hours on better, nutritious food.

This is how Arikomban earned his moniker as a lover of rice: he preferred helping himself to rice from villages than feeding on plants like eucalyptus and acacia found in the forests.

But the problem truly began when rumours of him disrupting human homes and causing casualties overtook his frequent raids for rice.

A possible solution to elephants venturing out of their habitats is zonation — to create non-edible buffer crops that keep elephants from coming out. But that’s a conversation for the long-term solution — the current debate amongst wildlife conservationists, animal rights activists and the forest department is about the ethics of capturing an elephant that is being destructive towards humans.

“The idea that elephants are always victims is incorrect, these elephants are coming out intentionally to eat nutritious food. But then again, you have to look at the needs and basic human rights of local people as well,” said Thekaekara. He explained how translocation is a stop gap emergency measure, the deeper drivers — the push of forests and pull into agricultural lands also needs to be addresses, or we will have a continuous stream of Arikomban-type situations.

“We need to be proactive instead of reactive, and plan much ahead. You don’t need to capture every elephant because it’s out of place — every elephant has different behaviours and needs. There are elephants who become so habituated that they don’t attack humans, and live in coexistence.”

Padayappa in Munnar, Rivaldo in Masinagudi and Ganesh in Gudalur are some examples of elephants that regularly venture out of the forest into nearby villages, and live in relative harmony with local communities. Padayappa is a local icon and is proudly flaunted by Munnar natives. Rivaldo has become an unofficial mascot of Masinagudi.

While wildlife conservationists, animal rights activists, and the forest department all have different perspectives when it comes to translocation, they all agree that a case-by-case approach is necessary to deal with the animals.

“What might work in Tamil Nadu might not work in Odisha,” said Bindumadhav. “India is a big, biodiverse country. Solutions need to be tailored to that particular instance, and there has to be community involvement. If a community isn’t involved, there won’t be ownership or responsibility,” he said.

He added that when we see an animal in conflict — whether it’s a leopard, an elephant, or even a snake — the impulse is to remove it from that area. But in doing so, they end up in worse instances of conflict than when they were captured. And often, if the Forest Department is willing to shift an animal due to conflict, it becomes the go-to ask.

“When we talk about promoting coexistence, depending on parameters of the situation, compromises may have to be made on either ends of this intersection. However, it can not be in the form of relocation of conflict animals,” added Bindumadhav.

Also read: Kerala temple robot-elephant huge in God’s own country. Revolutionary Raman must win hearts

Elephants without borders

Now, several Malayalis are demanding Arikomban’s return to Kerala’s Chinnakanal.

Somewhere along his journey, the elephant became a symbol of state pride: his strength, his spirit, and (not least) his affinity for rice resonated with Malayalis.

He has fan clubs on social media, and Sahu’s Twitter feed is full of requests for updates on the tusker.

Here is an update about wild elephant "Arikomban' as provided by the Field Director Mundanthurai Kalakkad Wildlife Tiger Reserve. Arikomban is feeding well and is settling well in his beautiful habitat of grasslands and pristine water bodies. Photo taken today by Team field team… pic.twitter.com/ZNcNMK9SIV

— Supriya Sahu IAS (@supriyasahuias) June 20, 2023

Many hope that this conversation sustains, and makes people think about viable solutions to man-animal conflicts without sidelining the needs of local tribal communities, who often bear the brunt of these conflicts.

Earlier, according to Jayachandran, people tended to side against animals in every case of conflict. Those who talked about protecting wildlife were called anti-development. Now, with heightened awareness around animal rights, those tables have turned — and protecting wildlife has taken a priority.

“We’re trying to do what’s best for local communities, and what’s best for the animals. It’s a delicate balance that the forest department has to maintain,” said Sahu, referring to the government’s role in negotiating these conflicts.

The question of whom the elephant belongs to is moot, according to Sahu. “Elephants don’t recognise man-made borders,” she added. “Governments can only do what they think is best. But ultimately, elephants like Arikomban are elephants without borders.”

On the ground in Idukki, Jayachandran agrees. “Arikomban belongs to nature,” he says with finality. “Not to an individual or a state.”

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)