In the three years since Supreme Court scrapped draconian Section 66A of the IT Act, Section 67, pertaining to the ‘publication or transmission of obscene material’, has emerged as an alternative.

Mumbai: In the three years since the Supreme Court scrapped the draconian Section 66A of the IT Act, Section 67, pertaining to the “publication or transmission of obscene material”, has emerged as an alternative to crack down on social media criticism of politicians.

Pavan Duggal, a cyber law expert, explains how this is possible.

“Section 67 is now invariably being used to fill up the vacuum created by the striking down of Section 66(A). The section has three ingredients and if any one of them is fulfilled, it becomes an offence,” he said.

“While the first two are clear, the third has a massive ability to be interpreted in a wide variety of circumstances. It refers to anyone publishing or transmitting material in an electronic form that tends to deprave and corrupt minds of the people. This is clearly not related to pornography and can be interpreted in any way,” said Duggal.

A conviction under Section 67 may earn a first-time offender a jail term of up to three years and a fine of up to Rs 5 lakh, while a subsequent conviction may mean imprisonment for up to five years and a fine of up to Rs 10 lakh. The punishment under Section 66A, introduced in 2009, was a maximum of three years in prison and fine.

A country-wide problem

As the use of social media exploded in India, with many using it to criticise politicians and their policies, leaders — across the spectrum — found in Section 66A a tool to check that criticism.

The first high-profile instance of its misuse took place in November 2012, when two girls questioned on Facebook the shutdown in Mumbai in the wake of Shiv Sena founder Bal Thackeray’s death. Two Air India cabin crew members were booked for sharing lewd jokes on politicians and making derogatory remarks about the then Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, while a Jadavpur University professor was arrested for a cartoon lampooning West Bengal CM Mamata Banerjee.

As a movement strengthened against Section 66A, dubbed a state weapon to curb dissent, a bunch of PILs led the Supreme Court to strike it down. The court said Section 66A “invades the right to free speech and upsets the balance between such a right and the reasonable restrictions that may be imposed on it”.

The two Mumbai men, who don’t know each other, have also been booked under the IPC sections relating to promoting enmity, defamation, criminal intimidation and making statements conducive to public mischief. Their case is the latest among a series where police have invoked Section 67 along with other sections of the IPC to punish social media comments and photographs deemed derogatory towards the government or certain politicians.

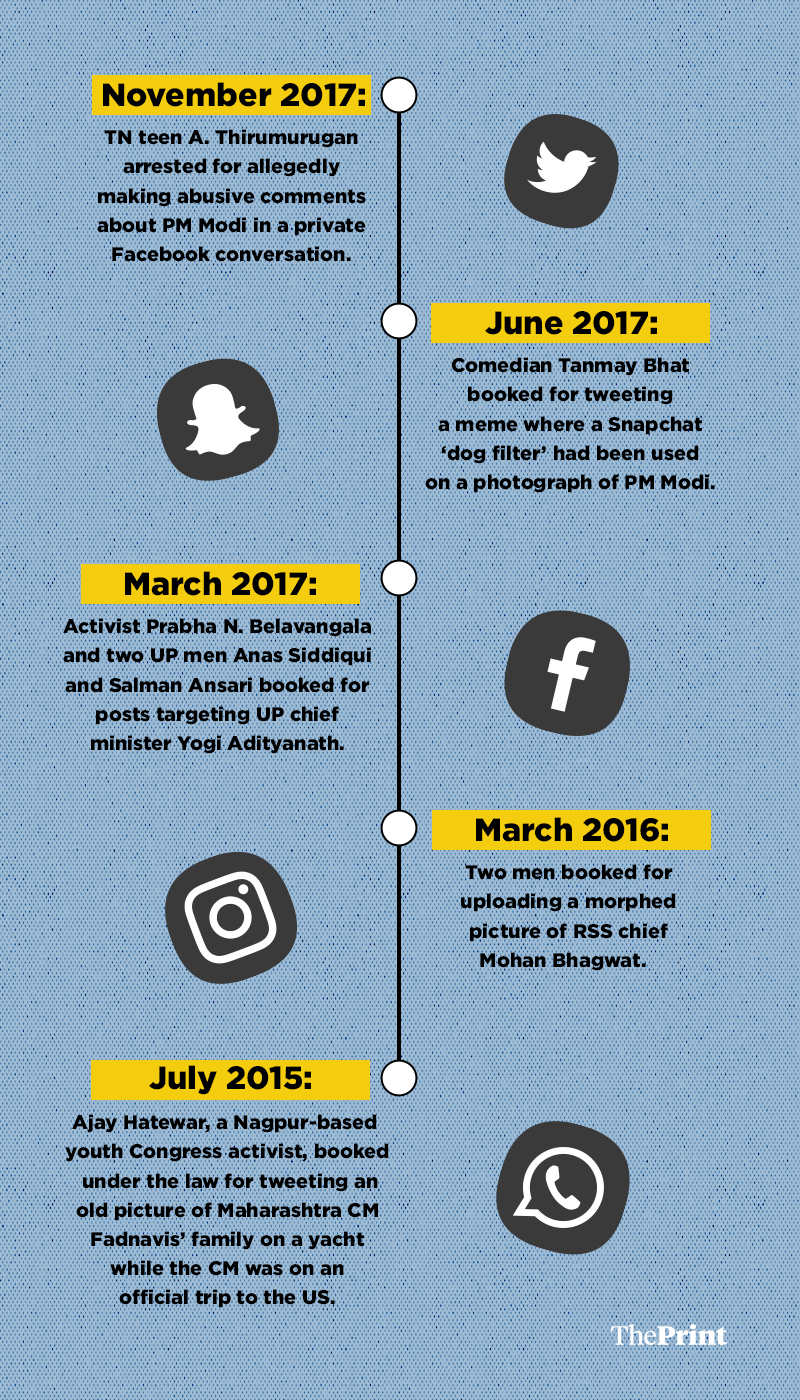

In November last year, A. Thirumurugan, a 19-year-old from Tamil Nadu, was arrested for allegedly making abusive comments about PM Modi in a private Facebook conversation. The teenager reportedly made the comments while responding to a meme about dialogues critical of GST in Tamil movie Mersal.

Last June, the cyber cell of the Mumbai police booked comedian Tanmay Bhat for tweeting a meme where a Snapchat ‘dog filter’ had been used on a photograph of PM Modi.

Then, in March 2017, Bengaluru-based activist Prabha N. Belavangala and two people from Uttar Pradesh, Anas Siddiqui of Amethi and Salman Ansari of Bareilly, found themselves under the scanner for posts targeting UP chief minister Yogi Adityanath. While Belavangala was accused of Facebook posts that depicted Adityanath in a poor light, Siddiqui and Ansari were arrested for posting “objectionable photographs” of him.

In March 2016, police in Madhya Pradesh invoked Section 67 against two men for uploading a morphed picture of Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh chief Mohan Bhagwat.

The year before, Ajay Hatewar, a Nagpur-based youth Congress activist, was booked under the IT Act for tweeting an old picture of Maharashtra CM Fadnavis’ family on a yacht while the CM was in the US on an official trip. The complainant claimed Hatewar had “defamed the CM” by linking the two trips.

Conviction by proxy?

Apar Gupta, lawyer and co-founder of the advocacy group Internet Freedom Foundation, said, “Going by anecdotal instances, press reports as well as data from the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB), there is a huge spike in the registration of cases under Section 67 of the IT Act (since 66A was scrapped). Police departments are using Section 67 as a proxy…”

Pointing out that the apex court had declared Section 66(A) unconstitutional for being vague and broad, he added, “It is ironic that police are using another section of obscenity that is just as vague and just as broad.”

According to NCRB data, a total of 957 cases were registered under Section 67 in 2016. Not all of these, however, necessarily related to a clampdown on speech on social media.

Priti Gandhi, a national executive member of the BJP Mahila Morcha and the complainant in the case against Patil and Subramanian, defended the action against the duo, saying there was a very thin line between dissent and abuse.