New Delhi: At a time when the name ‘Tipu Sultan’ can split any room into two sides, butting heads in favour and against the polarising historical figure, DAG’s new exhibition, ‘Tipu Sultan: Image & Distance’, brings to India art that offers a new lens — that of the East India Company artists.

Curated by Giles Tillotson, and now housed permanently as part of their collection at DAG, The Claridges, New Delhi, the exhibition gives a unique perspective on a controversial ruler. It showcases over 90 artworks, depicting war scenes and landscapes, among others, as well as three newspapers from 1799-1800. Many of these paintings were previously owned by private parties and museums like the Victoria and Albert Museum in Britain.

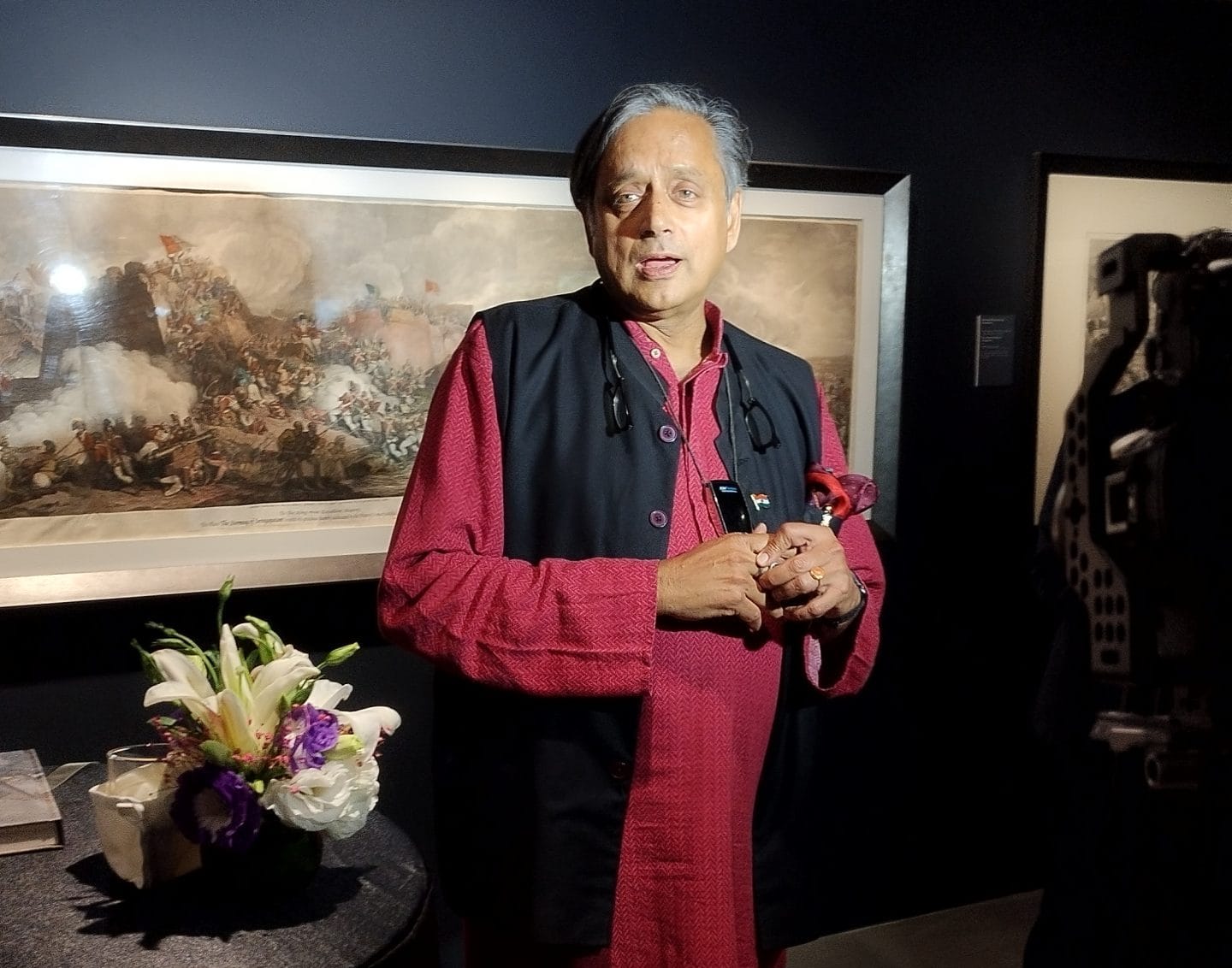

Inaugurated by Member of Parliament Shashi Tharoor on 25 July, ‘Tipu Sultan: Image & Distance’ showcases a visual history of the Mysore Wars between the EIC and the Muslim ruler. It also examines how the public narrative in both India and the UK was influenced by art and has coloured perceptions 222 years since the siege of Seringapatam.

While DAG and Tillotson are well aware of the contemporary socio-political flavour, they do not want to add to the current politics around Tipu Sultan. They just want to contribute to Indian historiography. Tillotson says, “We don’t want to step into the contemporary conversation surrounding Tipu Sultan but rather allow people to see a different perspective of him and provoke thoughts and questions.”

The EIC medal, known as the Seringapatam Medal, or Sri Ranga Pattana, was awarded to all British and Indian soldiers by the Governor-General of India for their victory in the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War of 1799. The medal highlights the defeat of Tipu Sultan, displaying the British lion trampling a tiger, the emblem of Tipu’s reign, along with the Urdu caption ‘Asad Allah al-Ghalib’ or ‘The Victorious Lion of God’.

Apart from paintings, the exhibition also displays historical objects like maps, ceramic and wood sculptures, and more.

Shashi Tharoor, while inaugurating the exhibit and the book delved into his own ambiguous family history associated with Tipu Sultan. Allegedly, Tharoor’s family fortune was hidden when the ruler was about to invade Malabar. It was never recovered. The Congress MP also recalled an incident when he was attacked by the Hindu Right for speaking in favour of Tipu Sultan during one of the many controversies surrounding the ruler in the South. However, he also emphasised on the significance of these works, saying, “We have seen that these British depictions of Tipu are, of course, unflattering. But it’s important to note what the perspective is.”

While these British artworks contribute significantly to the prevailing negative public history of Tipu Sultan, they also highlight an essential characteristic of art and its influence. Art cannot always be seen as an honest chronicler of the past. It often carries the prejudices of its maker, and, in the case of these British artworks, it highlights the agenda of the EIC, which aimed to vilify this historical figure. Revolutionary, despot, bigot — all three of Tipu’s histories are part of his complexities and the times he lived in. The EIC paintings at the exhibition are just one piece of the stained glass window.

Also read: Campaign for Kannada pride puts Immadi Pulakeshi over Shivaji, takes insider-vs-outsider twist

Art as propaganda

Showcasing primarily British artists’ works, one of the unique features of ‘Tipu Sultan: Image & Distance’ is that most of the scenes and landscapes are fictional, created to support the goals of the colonial empire. Based on the accounts of soldiers and other British officials, they focus on the demonisation and ‘dwarfication’ of Tipu Sultan.

“These works of art were not made for the Indian audience. They’re propagandist works made for a British audience to persuade them that the war was needed. I’ve deliberately taken them out of their context, both in time and space, to show them to a modern Indian audience,” says Tillotson while talking about the impact he hopes this exhibition will have on the contemporary political conversation surrounding Tipu Sultan in India.

Works such as Henry Singleton’s The Last Effort and Fall of Tippoo Sultaun (1809), Robert Ker Porter’s The Storming of Seringapatam (1802) and Singleton’s Tippoo Sultaun delivering to Gullum Alli Beg the Vakeel his two Sons (1793), among others, are all entirely fictional, created to influence British public opinion of the Mysore Wars and spread propaganda. Since many of these artists never actually visited India and mainly depended on officers’ accounts of the wars and conditions in the country, their works showcase the British officers as valiant and triumphant while vilifying Tipu Sultan as a tyrant torturing and killing his prisoners.

“To justify annihilating him, they have to turn him into a villain, which is exactly what they (the EIC) did,” says Tillotson.

The paintings also illustrate British ignorance of colonial India through their mislabelled temples as mosques, empty streets, neatly manicured landscapes, and more. An astonishing fact that the curator illustrates during his walkthrough of the exhibition was the misidentification of a Hindu temple in James Hunter’s A Moorish Mosque by publisher Orme, who never visited India.

Empty streets in Francis Swain Ward’s Fort Square, from the South side of the Parade, Fort St George (1805) and untouched landscapes in Thomas Daniell’s A View of Ossoore (1804), among others, stand out starkly for representations of a war-ravaged region.

The exhibition is accompanied by a book with the same title, Tipu Sultan: Image & Distance, with chapters by leading specialists on Tipu Sultan such as Janaki Nair, Jennifer Howes, and Savita Kumari. These essays explore numerous themes surrounding the ruler’s legacy.

Also read: Want to preserve secularism in India? Well, preserve the Hindu ethos first

Moving away from binaries

The contemporary conversation around Tipu Sultan continues to revolve around religion in India, turning him into a hot-button issue in cultural politics. Ever since the Karnataka Congress government in 2015 decided to celebrate ‘Hazrat Tipu Sultan Jayanti’ on 10 November, causing protests and heated debates with the BJP, Tipu Sultan’s legacy has been surrounded by disputes. While the Congress views him as a freedom fighter, the BJP sees him as a despotic, bigoted tyrant who killed innumerable Hindus.

Janki Nair, in her essay The Lives and Afterlives of Tipu Sultan of Mysore, probably says it best: “The large and sophisticated body of professional historical work on Tipu Sultan opens up an opportunity to leave binaries behind and strive for nonsectarian histories of conquest and conflict in India. This is no longer an option but an imperative.”

Where are the women?

You may ask this exact question while observing the various works at ‘Tipu Sultan: Image & Distance’. Most of the paintings focus on scenes of war or the lives of Tipu Sultan’s heirs. But none illustrate the fates of the hundreds of female courtiers living in his palace in Srirangapatna.

Exploring why women’s representation is neglected in the artworks, Jennifer Howes, in her essay The Women of Tipu Sultan’s Court, writes, “It is unsurprising that Tipu Sultan’s female courtiers went largely unnoticed in nineteenth-century accounts of Mysore, and that when they were portrayed in art, they were shown as voiceless victims to support imperialist attitudes about Tipu Sultan’s despotic character. What is surprising is how long it has taken to revise this simplistic understanding of Tipu’s court.”

Through her essay, she highlights the various historical scenes where women were entirely forgotten. Referring to Thomas Marriott’s recorded information, she concludes that there were, in fact, more than 600 women in Tipu’s court, belonging to various designations and trained in several languages and other skill sets.

Still, all these artworks cannot be brushed aside as simply depicting propagandist scenes. Certain ambiguities in these paintings can also lend opposing interpretations, moving away from the intentions and motives of their artists as well as those who commission them.

Henry Singleton’s The Last Effort and Fall of Tippoo Sultaun (1809), the painting that began the curation of this exhibition, is perhaps the most remarkable work representing Tipu Sultan’s fight against the EIC during the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War. Through this scene, Singleton aimed to showcase the British soldiers as brave and heroic, successfully defeating a demonic tyrant.

But talking about the imagined scene in Singleton’s work, Tillotson reveals an interesting observation, and he says: “One is to imagine that the unseen right hand of this fierce soldier is plunging a dagger into the side of Tipu. But I’m gonna add a note which none of us have dared to say. This is not the whole story. You can’t see the dagger at all. So is that what he’s really doing?”

Noting the piece’s ambiguity, Tillotson adds, “One version of the story from the English side suggests that the man who killed Tipu was, in fact, in the process of trying to steal his jewels. To me, Singleton is saying that the man who killed Tipu is not a heroic soldier or a valiant assassin, he’s a thief.”

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)