The busiest place in Bihar’s Saharsa district is the roadside tea and sattu shop outside the collectorate. Hundreds gather here every day and wait for the district magistrate’s car with their heavy paper folders of grievances. Their files would snake through the corridors, pile up on the dusty office shelves and languish for weeks and months, forming the Great Indian Red Tape. But that tape is being snipped away now since Saharsa district magistrate’s office went paperless.

It’s a mini-environment drive that also has massive efficiency spin-offs.

Now, the complaints reach the DM’s office not as a document file, but through online mode. What took three weeks of waiting time is now down to one day, say officials.

“This is an environmentally sustainable initiative and needs to be adopted in all offices,” said IAS officer Anand Sharma, the DM of Saharsa. In just six months, he brought an impressive makeover and transformed the dusty, dilapidated webbed walls of the collectorate.

Saharsa is the first district in Bihar to be declared paperless. But it was not a one-day magic event, Sharma said. The process takes time, training, brainstorming, and changing mindsets and behaviour.

The e-office initiative goes back to 2009, under the UPA government, but the towering piles of paperwork were–and still are–a hurdle too high to cross. A few district collectorates, though, made the transition before Saharsa. Idukki in Kerala became paperless in 2012 and Hyderabad in 2016. The Covid pandemic gave an impetus to the initiative with many district collectorates taking the digital route in 2020 and 2021 including Palakkad in Kerala, Jagatsinghpur in Odisha, Gwalior in Madhya Pradesh and Raigarh in Maharashtra.

The steel frame of Indian bureaucracy typically stands on top of a mountain of paper files. In Saharsa, a huge bundle of critical files from the collectorate would be ferried every day on scooty to the gopniye (secret) room at the DM’s residence. The whole process weighed down decision-making time.

Raj Kumar Sada and Umesh Chaudhary from Kachaut village in Salkhua Block had to travel 40 km with a darkhwast (complaint) to meet DM Sharma about their land dispute cases.

“Unlike before, this time we saw that our files were scanned, which boosted our confidence that it won’t get lost anywhere,” Chaudhary said, referring to people’s fears about files getting misplaced in the dense bureaucratic maze.

Also read: Rule of law and rural tradition – how women judges are walking the tightrope in Rajasthan

Policies in departments, implementation in hinterlands

Anand Sharma, a 2013-batch IAS officer and Faculty of Management Studies graduate, quit his marketing job at Hindustan Petroleum to join the services. Going by his past record, it is apparent that he is a passionate advocate of paperless efficiency.

He turned the Cooperative Department in Patna paperless. It was Bihar’s first government department to make the digital transition in 2020.

“That experience stayed with me,” Sharma said. There was no stopping him now. With the zeal of an evangelist, he brought the concept of an e-office to the Patna Metro Rail Corporation and then to the Urban Development and Housing Department.

Sharma took charge as the DM of Saharsa in January this year. This was the real test. He said it was easier to introduce reforms in the capital city Patna than in the hinterland. But it was also more important. “Policies are made in departments but implementation happens in districts,” he said. “But it’s not an easy task to overhaul the system that has been in place for decades. All the staff were used to it.”

The pandemic forced officers to change the old ways of working. It was also a lean period for the administration and Sharma took advantage of it. He zeroed in on younger, tech-savvy employees in every section and made them the master trainers of his project. After several brainstorming sessions, everybody was trained to work online.

Initially, the officers of the collectorate were hesitant. It was too big a change and quite unimaginable for many. “When Sir [Anand Sharma] was new, we were all very scared of him, he was bringing such a big change. Few here have technical knowledge of computers,” an officer at the collectorate said on condition of anonymity.

But 10 February was the turning point. The first e-file was processed. After that, there was no going back for Saharsa.

“Sir changed the entire system. Now, everyone from staff to officers is working on computers or laptops,” said Manoj Jha, a staff member at the collectorate, which has as many as 200 staff and officers on its payroll. None of them imagined a day when their desks would be clear of case files and paperwork. “He brought a change that nobody thought of,” Jha added.

Changing mindsets, bringing efficiency

From past experience, Sharma knew that the toughest hurdle would be to change people’s attitudes and mental dispositions.

“We can give resources, computers, printers. But until people are willing to change their minds, change will not be possible,” said Sharma, who had to draw deep from his well of patience.

During one training session, a clerk, at the far end of his retirement, said, “It is not possible for us to use a computer at this age.” The IAS officer did not lose his temper but instead encouraged him to “just start.” He promised the clerk that he would not be alone and that Sharma would be there to help him should “he get stuck”.

“I was not angry because his concern was genuine,” said Sharma.

Now that they have bridged the digital divide, staff members of the collectorate are not missing the reams and reams of documents and piles of case files. “Everything is on track and we are happy to get rid of the papers,” said Parshuram Pawan, a staff member who trained other co-workers and officers.

But the ghosts of past documents continue to haunt the collectorate. Staff members have to figure out a way to store hard copies of case files that are already digitised. They are needed for either legal or audit-related purposes. The collectorate has asked the state government for document compactors to help them.

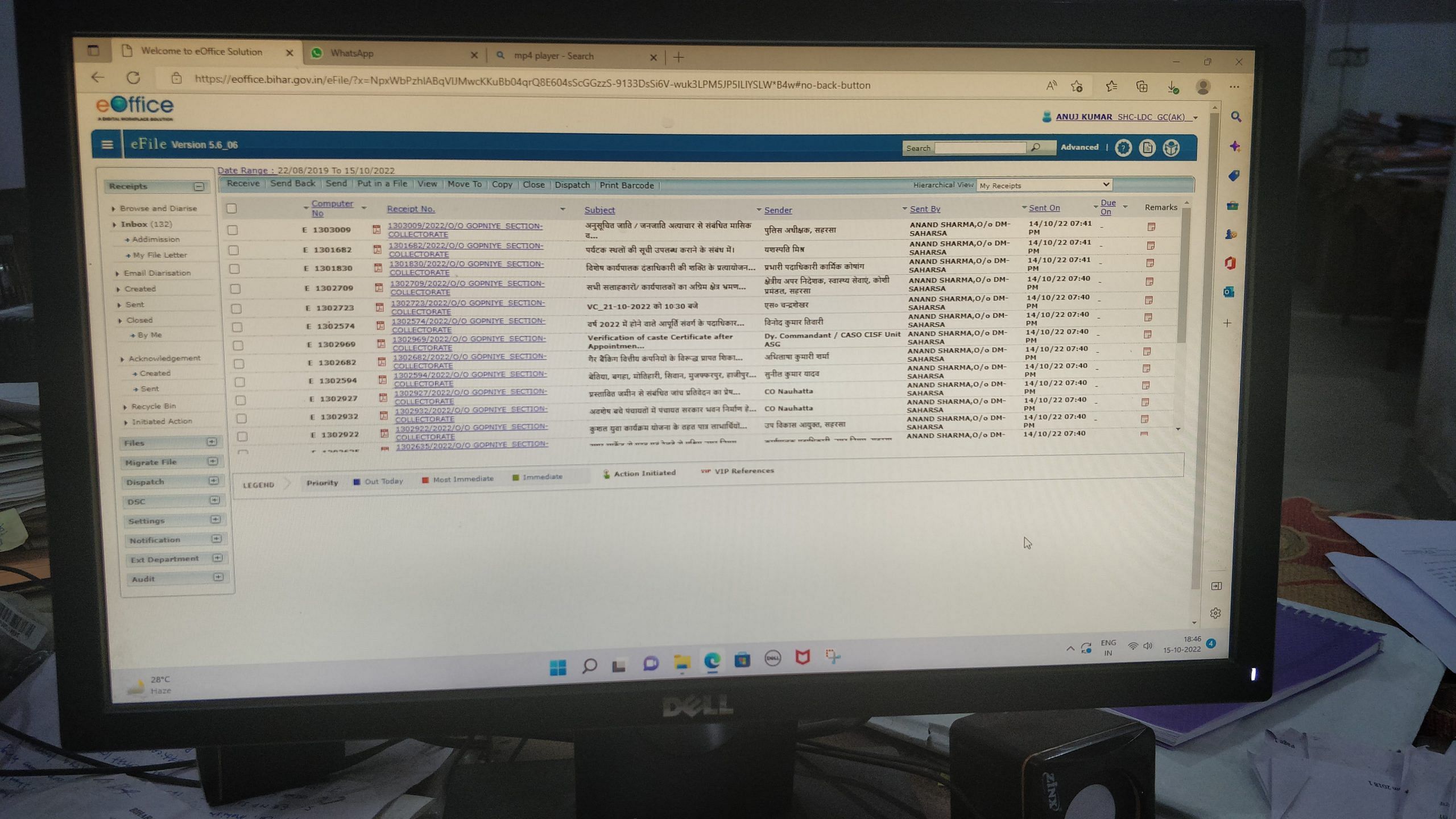

So far, about four lakh pages—mostly from active files—have been scanned at the cost of 34 paise a page. And 6,103 files have been created on the e-office platform.

A high-speed scanner whirs and beeps in the background as it converts hard copies into digital images. Even letters that the collectorate receives are fed to the machine after which the soft copies are uploaded on the e-office platform before being carefully labelled and tagged.

Now, on average, 27 files are disposed of every day. In the ‘paper era,’ one file would take as long as three to four days to process. It’s not just saving the government’s time and money, but slowly instilling faith in the public. “We transfer files to departments with the click of a button,” said a staffer.

Between 1 March and 31 August, as many as 4,106 files were disposed of. It is a huge improvement compared to the same period in 2021 when only 1,158 files were cleared.

Also read: ‘Modi diluting Yogi’s anti-incumbency’ and other trends from Uttar Pradesh’s hinterland

A step towards good governance

Digitisation has helped Sharma bring about efficiency, transparency and accountability. From his laptop, he can track the movement of each and every file, and see where it is getting held up. There are no cracks in the system.

Since files are processed within a day, it has increased employee productivity. And the number of people required to process a single file has reduced. “In the government system, it is said that the faster a file moves, the faster a policy will be implemented,” said Sharma. Already, welfare programmes and government-led initiatives are being approved faster.

The online system has also brought in more accountability. Staff members cannot sit on files for days on end. And Sharma sets the pace. “If I can dispose of a file within a day, then so should my team. Everyone is under the scanner, and monitoring is quite easy,” he added.

Sharma is not stopping at the collectorate. After the district-level reform, he now wants to move it down to the two subdivisions—Saharsa Sadar and Simri Bakhtiyarpur.

Technology is his first step towards good governance and a corruption-free system. “This will happen only when we go to the district, then to the subdivision and then to the block. The more technology we implement, the easier our service delivery will be to the public.”

The unbearable lightness of paperlessness is an idea whose time has come for Saharsa.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)