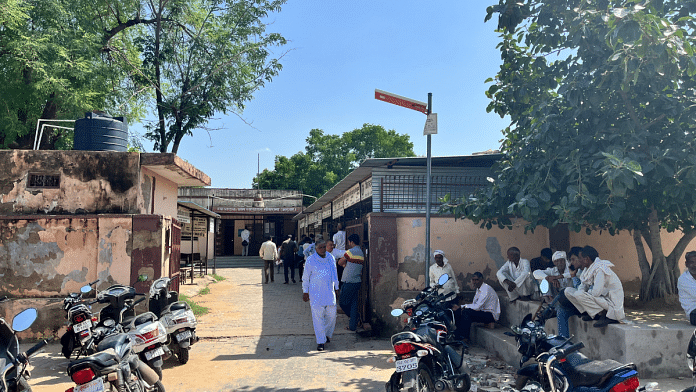

Tijara/Neemrana: In a sea of nearly a hundred men—cops, litigants, villagers, and stenographers—stands a lone veiled woman. Beena Rajput has travelled seven kilometres from a neighbouring village with the strong belief that “ladies understand ladies”. The men are alert. ‘Madam Judge’ is about to arrive.

Mandhan village in Rajasthan’s Alwar district hums with anticipation; orderlies, stenographers and clerks have transformed the Panchayat Bhawan into a busy courtroom. They’ve converted a table into a dais, and even the sarpanch has bestirred himself to ensure that the tumblers are filled with water. A banner across the hall–Gram Nyayalaya Neemrana–explains the activity.

In one corner, Beena stands clutching her file on a two-year-old physical assault case, her face completely covered by her green saree. She is an outsider. And the only thing that has brought her to this village court is the knowledge that her statement will be heard by a lady judge.

This is not just another courtroom, but a mobile court, a gram nyayalaya, within the Indian judicial system–an alternative forum to provide doorstep justice. Over 70 per cent of the judges in Rajasthan’s Gram Nyayalayas are women, negotiating the tricky but fragile space between rule of law, social traditions and hierarchies, and the rural practice of rough-and-ready justice. It’s empowering for the judges as well. The absence of a man telling them how to run their courts is particularly freeing.

“There is always this paternal figure in the district headquarters telling you how to run the courtroom. But as a Nyayadhikari, you get to run the whole show. From independently running the administration to fulfilling your duty as a judge. You learn a lot,” said a woman judge who has served in the Gram Nyayalaya.

Around 12 pm, the magistrate, Saroj Choudhary, enters the room. She’s holding a book on ‘Criminal Major Acts’ in one hand, and a tiffin box in the other. Soon, it’s Beena’s turn to come up to the front of the makeshift courtroom and state her case. The court records her statement.

“I was beaten up thrice by my brother-in-law for attending a neighbour’s

wedding,” said Beena, clutching a copy of the FIR. Now, she is under

pressure from her husband to patch up with his brother and withdraw the case. “There’s a focus on compromise in cases brought in by women. There is no awareness about women’s rights at all.” Chaudhary remarked.

Rajasthan has 45 such Gram Nyayalayas, and more than a dozen women judges like Chaudhary are delivering justice with a deft touch–careful not to upset the apple cart of caste and gender unless

absolutely necessary. “Justice in rural India is a very delicate matter. Your legality clashes with their morality. You negotiate justice with them. It does not require a hard-hitting hammer, but a surgeon’s scissor,” said a serving woman judge.

Also read: Eight out of 10 Rajasthan judicial exam toppers were women. Get ready for army of female judges

The still evolving concept of a rural court

Thirty-five-year-old Saroj Chaudhary, a magistrate from the 2016 RJS batch, is no novice. She’s held at least a hundred mobile courts since March 2020 when she was posted as Nyayadhikari in Alwar’s Neemrana tehsil. She routinely walks this tightrope between patriarchy and the law. And residents of Mandhan, too, have come to accept a woman judge.

Chaudhary is their fourth female magistrate. “Madam understands our

language and it becomes easy for litigants to communicate with her,” said Surender Yadav, sarpanch of Mandhan village. The Gram Nyayalaya Act, which awards states the responsibility to establish these courts, came into existence in 2008. It was one of the answers to India’s case pendency problem. There are currently around 4.5 crore pending cases, of which 87.6 per cent are in the lower courts.

Despite the Act in place, the concept of a rural court is still evolving. Currently, there are only 258 functional rural courts in 10 states. One of them is the Neemrana Gram Nyayalaya, which was established in 2011.

The Union government has issued notices to set up 476 Gram Nyayalayas, and has allocated Rs 50 crore for it.

These rural courts rule on both civil and criminal matters but are limited to cases where the offence is punishable by less than two years in jail. Land disputes, family feuds and assault are the more common cases in Indian villages. The rural court’s intervention in both civil and criminal matters is in sync with the practical reality of society.

G Mohan Gopal, former director of National Judicial Academy and former VC of the National Law School of India (Bengaluru) said, “Undoubtedly, access to justice of common people in India is abysmal.”

He added that the ratio of new cases filed in a year per 1,000 population is useful for determining the access to justice gap. This ratio is about 5 new cases per 1,000 population in Bihar; 8 in Tamil Nadu; 16 in Uttar Pradesh; some 18 new cases in India as a whole. While some 20 new cases are in Delhi and around 22 new cases in Kerala.

“In contrast, there are about 52 new cases in Singapore (2019), 62 new cases in the UK (2019) and some 300 new cases per 1,000 population in the US. It is not as if there is less violation of rights in Bihar than in Kerala — it is just that there is less access to justice,” Gopal explained.

Gram Nyayalayas can play an important role in bridging this yawning access to justice gap. They can bring justice to the doorstep of the poor, he added.

“The challenge is that these Nyayalayas should not degenerate into Khap panchayats legitimised by the presence of judicial officers. They should not become a counter-constitutional institution, upholding the existing social order. They must be the frontline force of the Constitution. They must be grass roots guardians of fundamental rights to equality, liberty, dignity and fraternity and of democracy and the rule of law, protecting the powerless against the powerful. They must safeguard secularism, proactively challenge caste, gender and class inequality, They must protect the environment,” Gopal said.

He added that Gram Nyayalayas must be provided with all the tools and resources necessary to play this role.

Villagers prefer this to the more formal district courts or court kachaharis. “Disputes in villages were earlier settled within the panchayat. Court kachahari was dreaded,” said Ankit Yadav, the village secretary.

Yadav told ThePrint that at first everyone knew how witnesses are manipulated in courts. “People believed that the village elders are more familiar with everything that goes around in the locality, they would deliver a balanced judgment. Also, ladies would not go to the courts because it was a matter of sharam-lihaz (shame). Even if a matter reached the police station, the focus was on dropping women’s names.” he added.

If the villagers were to put aside their reservations, the Gram Nyayalaya judges, particularly the women, would have to learn on the job.

It’s a work in progress.

“We didn’t really get to know much about how to run a Gram Nyayalaya in our judicial training,” said a woman judge who had served as a Nyayadhikari. Law courses and universities barely cover the subject. “And if you Google keywords such as Gram Nyayalaya, you would not find research papers. In the absence of information, we rely on our personal experiences,” she added.

Fund constraints, infrastructure such as where to set up the mobile court, accommodation, transport arrangements, and lack of human resources are some of the other challenges that judges and magistrates face.

But when infrastructure is lacking, it becomes difficult for women to run the Gram Nyayalayas. According to a notice of the Allahabad High Court in July, Uttar Pradesh recalled 24 female judicial officers from rural courts to the district headquarters due to a lack of resources.

The Neemrana Gram Nyayalaya has two practising female lawyers, and women like Beena are not stopped from pleading their cases. But there are Gram Nyayalayas where women are non-existent.

Also read: Stalkers, creepy 1 am emails, flowers – What two women judges in small towns battled

Lack of proper infrastructure

Sakshi Chaudhary, another magistrate from Alwar district, is preparing to hold a Gram Nyayalaya in Tijara, 65 kilometres from Neemrana, where Saroj Chaudhary works.

Both Chaudhary women graduated from the same batch six years ago and began their professional careers as the first female officers in their respective tehsils—Sakshi in Neem-ka-thana in Sikar district and Saroj in Nagaur district’s Degana.

But now, they face different challenges even though they are posted in the same district. While Neemrana is largely an industrial and aspiring belt, Tijara battles widespread illiteracy and a lack of proper infrastructure.

There are no women in Sakshi’s courtroom. Village elders actively discourage women litigants and plaintiffs who are not even allowed in the Gram Nyayalaya.

“It becomes difficult for Madam [Sakshi] to conduct regular camps in some villages for security reasons. They don’t allow women to join the camps, even when they are the witnesses in some cases,” a senior courtroom staffer at the Tijara Gram Nyayalaya said.

In comparison, the situation is marginally better in Mandhan village. “If we request them to come to the panchayat, at least some of the female ward members appear, with their veil intact,” Surender Chaudhary, the village head said.

Also read: Bangs, lipstick, low neckline—for Indian woman lawyers, merit evaluation steeped in misogyny

Disposing cases, instilling behavioural changes

Every second Friday, proceedings at a Gram Nyayalaya can last up to five hours, if not longer. Saroj has hundreds of cases, and the proceedings don’t seem to make a dent in the pile of cases on her table.

After Beena’s case, a family dispute is next on the agenda. She asks the litigants to step forward. Virender Yadav, a farmer from nearby Kanhawas village who was allegedly attacked by his younger brothers in a row over a tube well, gets up. But his wife, who is also named, is not in the court.

“Where is the woman?” Saroj asked the constable whose job was to deliver the summons. Someone is dispatched to bring the woman to court. Meanwhile, the family feud begins unfolding as the agitated Yadav brothers start hurling accusations at each other.

“Look at the injury, it is not healed yet,” Virender shouted above the din while removing his pagadi. His brothers leap into the fray and begin unfolding various items of clothing to show the magistrate their injuries. Chaudhary quickly intervenes to establish order.

“This is a courtroom. Please maintain decorum,” she commands. With emotions running high she chooses to appeal to their fraternal bonds.

“He is much older and ready to forgive you. You must show a large heart and not indulge in such petty crime,” she told the men. The Yadav brothers grudgingly make up with each other and shuffle out of the court. Virender’s wife appears at the end of the proceedings and gives her statement.

Chaudhary calls out another name. A Scheduled Caste man has been accused of playing loud music in his truck, disrupting the peace of the village. “Where do you live? How much do you earn? “Will you do it again?” Chaudhary asked him. “I will never do it again madam,” he pleads. She imposes a penalty of Rs 200 and lets him go with a warning.

Saroj goes through the files, occasionally instructing the stenographer sitting next to her to make some changes. It’s evening, and the room smells of smoke from hookahs and bidi as farmers come and go. It is the mustard-sowing season and everyone is busy.

“Next,” says Saroj.

This is part of a series on women judges in India’s lower judiciary. Read all the articles here.

(Edited by Tarannum Khan)