There is something that a tailor from Delhi shares with a labourer from Deoria and a used car salesman from Jalgaon—a deafening void around the matter of death penalty.

Sunita Nagpal and her husband Mahender were forced to change six houses in three years. Munilal Gaud had to sell his ancestral land to pay their lawyers. And 18-year-old Nusaiba’s only memories of her father are from hurried meetings in court corridors and letters he wrote from prison.

A common factor unites all these families–they have a loved one currently on death row.

India has a strong provision to award death penalty only in the ‘rarest of rare’ cases, but increasingly, there is concern that the number of convicts on death row is on the rise, and that the lower courts are less reluctant to give capital punishment.

In India’s jurisprudence, the term “collective conscience” of the society first appeared in the landmark 1983 Machhi Singh judgment. It has since been used by courts to confirm death penalties for Afzal Guru, Ajmal Kasab and Delhi gang rape convicts in the past decade.

But India’s movement to end capital punishment has been thin and patchy, and has largely revolved around the morality of sending someone to the gallows. This is now changing with a new focus on the courts’ role and readiness.

Prison reform advocates often say that incarcerating one person also means incarcerating their entire family. It is worse for families with a convict on death row — their lives are stuck in a liminal space.

“Life has stopped completely. We don’t know if our son will come back or not,” said Sunita Nagpal. Her son Jeevak was convicted in September 2020 for the kidnapping and murder of his 12-year old neighbour, and awarded death penalty the following month. For Sunita, any thought of the future is marked by conflicting emotions of hope and despair.

“Our life will start again only when he comes back…or goes away forever.”

Also read: 65% death sentences by trial courts in 2020 involved sexual offences, study reveals

‘Khooni ki maa’

In the 12 years since Jeevak Nagpal’s arrest on 19 March 2009, Delhi’s Rohini district court had an almost permanent visitor–his mother. Sunita would sit on the steel benches of the court, knitting.

Jeevak’s appeal against the verdict is currently pending in the Delhi High Court.

Since his arrest, the clicking-clacking of the knitting needles have become a constant in Sunita’s life, marking the passing of time.

She and her husband Mahender had to spend a night at the New Delhi Railway Station in March 2009, when the keys to their house were taken over for investigation. After Jeevak’s arrest, they had to move houses six times in three years. Every time property dealers learnt about the case, they were asked to vacate.

When they moved to Pitampura a month after their son’s arrest, a visit by the police gave them away.

“I left the house an hour later, and people were staring. They started calling me ‘khooni ki maa’ (murderer’s mother) wherever I went… I have often walked out of the house with a ghoonghat covering my face, crying the whole way,” Sunita said.

The family moved to another house in Pitampura within a few months, before relocating to Rohini. In 2012, they were asked to vacate the house within two days, but they shut themselves in the house for two days. “All three of us [Sunita, her husband and her youngest son] didn’t step out at all. Finally I went to the property dealer and told him, ‘If my son has done this, he is suffering for it. We haven’t done anything’.” It didn’t help their cause. The family had to vacate the house in a month and half.

Also read: Seven other countries where the punishment for rape is death

Entirely a judge’s call

In India, more than 55 sections of the Indian Penal Code (IPC) allow for death penalty for offences considered grave and heinous. These include murder and rape of a child below 12 years of age, as well as terrorism-related acts under special laws like the Maharashtra Control of Organised Crime Act 1999.

Of late, the conversation around death penalty has taken a more nuanced approach, with many arguing that it is arbitrary and judge-specific. The movement for a deeper scrutiny of such cases reached the Supreme Court of India in April this year.

The court decided to put in place a mechanism by which crucial information — to decide whether a person should be condemned to death or not — can be gathered and submitted before trial judges. The Supreme Court also pondered on whether courts are opting for death penalty too soon without making an effort to unearth or understand the circumstances that led the person to commit the crime.

Last year, 30 convicts on death row were acquitted by six high courts across the country through 15 judgments, which pulled up investigators for manufactured FIRs, coached witnesses, and lack of proper legal aid. Trial courts were pulled up for their assessment of evidence, or rather the lack of it.

In short, trial judges often don’t know who they are sending to the gallows.

But the people who know the guilty are their families—their mothers and fathers, brothers and sisters, daughters and sons. Their stories read like remakes of the same script written in different languages, each telling the same tale. The common narrative spine is their entanglement with a maze-like judicial system, especially for those who do not have the financial and social capital to navigate that system.

These families are left behind to bear the collective outrage and condemnation of society. Guilty by association, they face unparalleled stigma as soon as their kin is arrested in a death penalty crime. They are marginalised and ostracised. They are forced out of jobs, deemed unhirable, and often fall into debt.

“As a society, we conveniently ignore this suffering and sometimes even think of it as justified collateral damage,” said Dr Anup Surendranath, executive director of Project 39A at the National Law University, Delhi. He calls the families of death row prisoners “secondary victims”.

“It can’t be a justification to say that we can inflict suffering on a death row prisoner’s family because suffering was inflicted on the victim’s family,” he said.

Also read: UP woman who axed family to death likely to become India’s first female to be executed

‘Never going back’

More often than not, the marginalisation and ostracisation begins within the family. Relatives start distancing themselves, and it doesn’t take long before the stigma spills over to other parts of their lives.

Thirty-year-old Ramkirat’s father Munilal Gaud, and his brother Shyamkirat, also became “secondary victims” more than seven years ago. In October 2013, Ramkirat was arrested from a watchmen’s chawl in Thane, for raping and killing a three-year-old girl.

Soon after the arrest, Manilal and Shyamkirat—who also worked as watchmen in nearby societies—were asked to leave the chawl and their jobs.

They returned to their hometown in Deoria, Uttar Pradesh.

Munilal then sold five biswa (about 6,750 sq ft) of ancestral land in his village to pay lawyers at the trial court and the Bombay High Court. The duo now work as daily labourers tending to other people’s rice and wheat fields.

Shyamkirat also sworn off Mumbai. “He hasn’t gone back since then. He says he won’t ever go back there now,” Munilal said of his son’s resolve.

Ramkirat was convicted in March 2019 and awarded the death penalty. An appeal against this judgment is pending in the Supreme Court. He is currently lodged in Pune’s Yerawada Central Jail.

Ramkirat has three children, but none of them attend school.

“Everything is gone now…What is the income here? You just earn and eat. But how many days will someone live eating chutney roti, salt roti?” Munilal asks.

When Asif Khan, now 42 years old, was arrested on 3 October 2006 from Belgaum for the 2006 Mumbai train bombings, his younger brother Aziz suffered the consequences. His company distanced itself from him for about half a year, asking him to not come to office. Aziz was able to find a job, while Asif remained on death row for seven years.

The family has confined itself to the Muslim-majority basti of Shirsoli naka in Jalgaon where neighbours are supportive and the family feels comfortable. But in the next gali (lane), no one knows about the case or the family.

Asif was convicted by a Mumbai court in September 2015, and put on death row along with four others. He remains incarcerated at Pune’s Yerawada jail. For the past seven years, the appeals have been pending in the Bombay High Court that is too ‘overburdened’ to take them up.

Also read: Slain family, woman & lover on death row, boy born in jail — this Amroha home has a gory story

‘Wish him a bright future’

After the arrest and even after conviction, there are three ways in which family members of prisoners can get in touch with them—through mulaqaat (meeting), telephone call and letter.

Before Covid, these meetings were usually in a room crowded with other prisoners.

Now, virtually, they are allowed to talk to their families through a glass window over the phone–often for barely 10 minutes. These visits provide a few families a brief window to share their lives, but many are hesitant to burden each other with their troubles. Each person on either side of the glass believes their stories are smaller, less significant than the other’s.

For Jeevak and his parents, these meetings are often a well rehearsed dance of pleasantries.

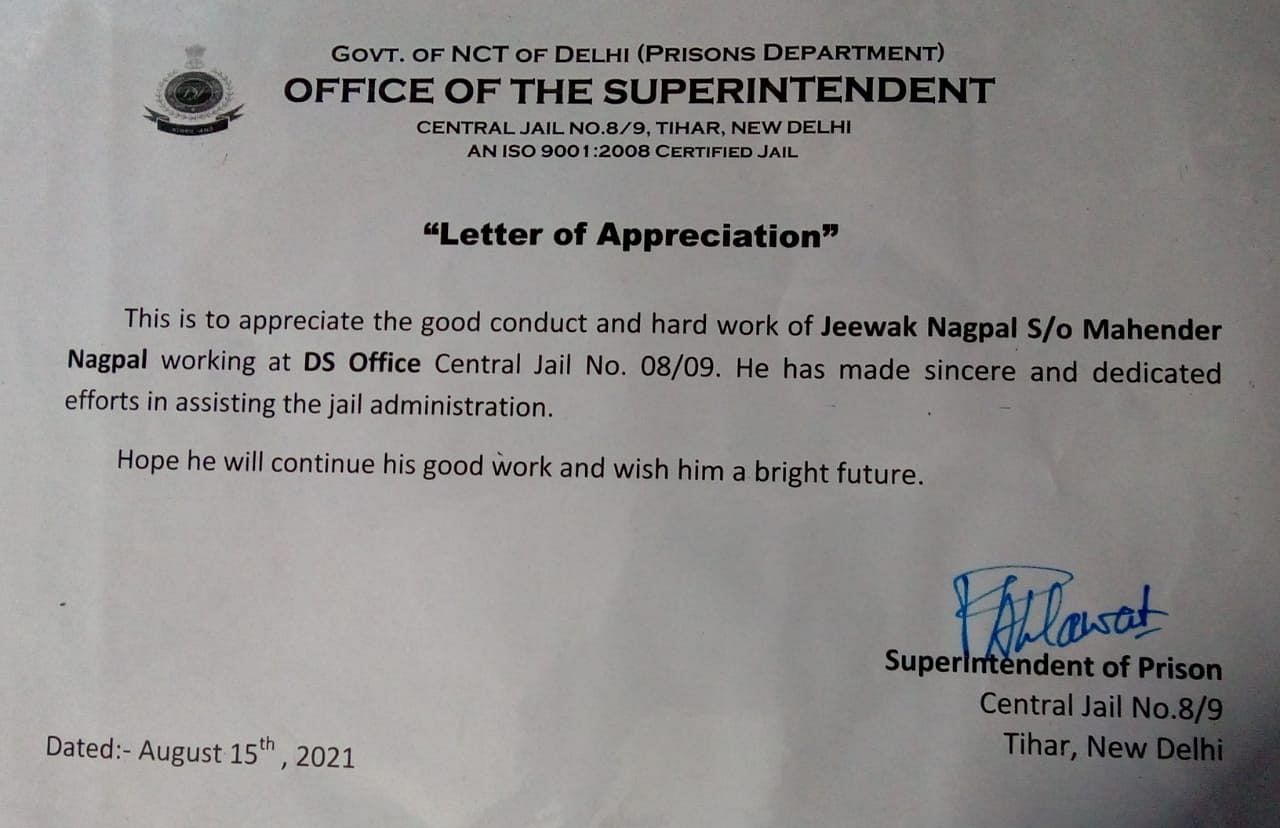

“We don’t have much to talk about anymore. We ask how his health is, he asks how everything is at home,” his mother said. They use the prison guards to exchange physical manifestations of these assurances–Jeevak’s mother passes on clothes and other essentials to him that she carefully picks out for him before every visit, while Jeevak gives her the trophies and certificates that he wins inside the jail.

One of the trophies says he won the first prize in a badminton tournament in Jail no. 8. Another is a second prize in a chess tournament. A certificate issued by the office of jail superintendent appreciated his “good conduct and hard work” in jail.

Ironically, the certificate issued ten months after he was awarded the death sentence, said, “Hope he will continue his good work and wish him a bright future.”

Surendranath explains that these mulaqaats hold tremendous significance for prisoners and their families. “The suffering and horror of being on death row, fearing death and the constant oscillation between hope and despair is torture. Coping with that is a challenge we can’t really comprehend. In that situation, support systems are crucial for survival.”

However, mulaqaats aren’t always possible—sometimes because of the costs involved in the travel, or due to ill health, and at other times due to social prohibition on maintaining contact with the death row prisoner.

Ramkirat’s wife Savitridevi has met her husband only once in the nine years that he has been in prison. His father Munilal goes to meet him two to three times a year. “Where do I get the money for his wife and kids to go see him? Every time it is about Rs 400-500 for a ticket,” he said.

Also read: ‘Rarest of rare’ — history of death penalty in India and crimes that call for hanging

The green almirah

Asif often begins his letters to his daughter with ‘Pyaari pyaari Nusaiba beti’. Nusaiba was three years old and Ayesha was five when he was arrested after the train blasts. Nusaiba’s earliest memory of her father is sharing a meal with him during the lunch break outside a courtroom in Mumbai, surrounded by policemen.

Now, Asif’s presence in their house has been replaced with a cardboard box on top of a green, rusted aluminium almirah. It contains all the legal documents as well as the letters that he writes to them from jail.

In one letter, Asif assumes the role of a teacher and tells Nusaiba how to write her name in Urdu. In another, he expresses pride over her board exam results. “Prepare for NEET, inshallah you’ll get a good rank. But still, we shouldn’t get too stressed, or take it to heart. There are many options for further studies,” he tells his daughter.

Among the 12 convicted for the 2006 local train blasts were two brothers—Muzammil and Faizal. Muzammil is currently on life term and Faizal is on death row. Their mother, Parveen, last met her sons in April 2019, four months after her husband, Ataur Rahman, passed away.

“He (Ataur Rahman) met both of them and had a heart attack three days later. He used to worry about them a lot,” Parveen said.

With age, contact with her sons is now reduced to the occasional phone call and letters. Parveen suffered a stroke last year and experiences momentary memory losses through the day. She confuses the names of her sons. Muzammil often becomes Faizal and Faizal becomes Muzammil, until she fumbles and corrects herself.

She can’t walk too much anymore, so she is usually confined to the plastic chair in her drawing room all day, looking at passersby through the grilled balcony, and waiting for her sons’ calls and letters. However, while Faizal writes at least one letter a month, Muzammil writes to her once or twice in a year.

“Muzammil is lazy,” Parveen adds with a laugh.

Also read: ‘False evidence, tainted cops’: Why 15 HC verdicts freed 30 death row convicts last year

A complete picture

In May 1980, a five-judge bench of the Supreme Court upheld the constitutional validity of capital punishment. The court, however, clarified that judges need to take into account aggravating and mitigating factors about the crime and the accused.

But since then, experts say “it appears this judicial framework has collapsed.”

They attribute this failure to several factors, including the sole focus of judges on aggravating factors like the gravity of the crime, and insufficient emphasis on mitigating factors.

Mitigating factors are not meant to justify the offence. Instead, they provide a complete picture of the convict: their formative years, developmental history, education, occupational history, trauma, access to nutrition, shelter, family history of physical and mental health, conduct in jail, emotional and psychological state, and their appreciation of the wrongfulness of the act.

Legal experts have also highlighted the inequality in the system. A 2016 study showed that 74.1 per cent of prisoners sentenced to death in India were economically vulnerable, and 76 per cent belonged to backward/deprived classes and religious minorities.

Article 39A of the Indian Constitution guarantees free legal aid. However, Surendranath argues that families hire private lawyers due to “an immense lack of faith and even fear of state-provided legal representation”. According to him, this attitude towards legal aid is driven by “concerns of collusion of legal aid lawyers with the other side, corruption, and ineffectiveness”.

With this understanding of a collapsing system, the Supreme Court initiated a petition in April this year to develop guidelines to be followed by all courts while considering matters that involve death penalty. In May this year, another bench of the apex court also issued guidelines and made psychological evaluation of the condemned prisoner mandatory.

However, critics argue that legal jurisprudence cannot translate into effective changes on the ground, unless it is backed by a criminal justice system and an administration that can implement it with fairness.

Also read: Convicts of gruesome crimes deserve punishment, not death

The invisibility cloak

When the possibility of a death penalty becomes a reality, convicts and their families find their own ways to cope.

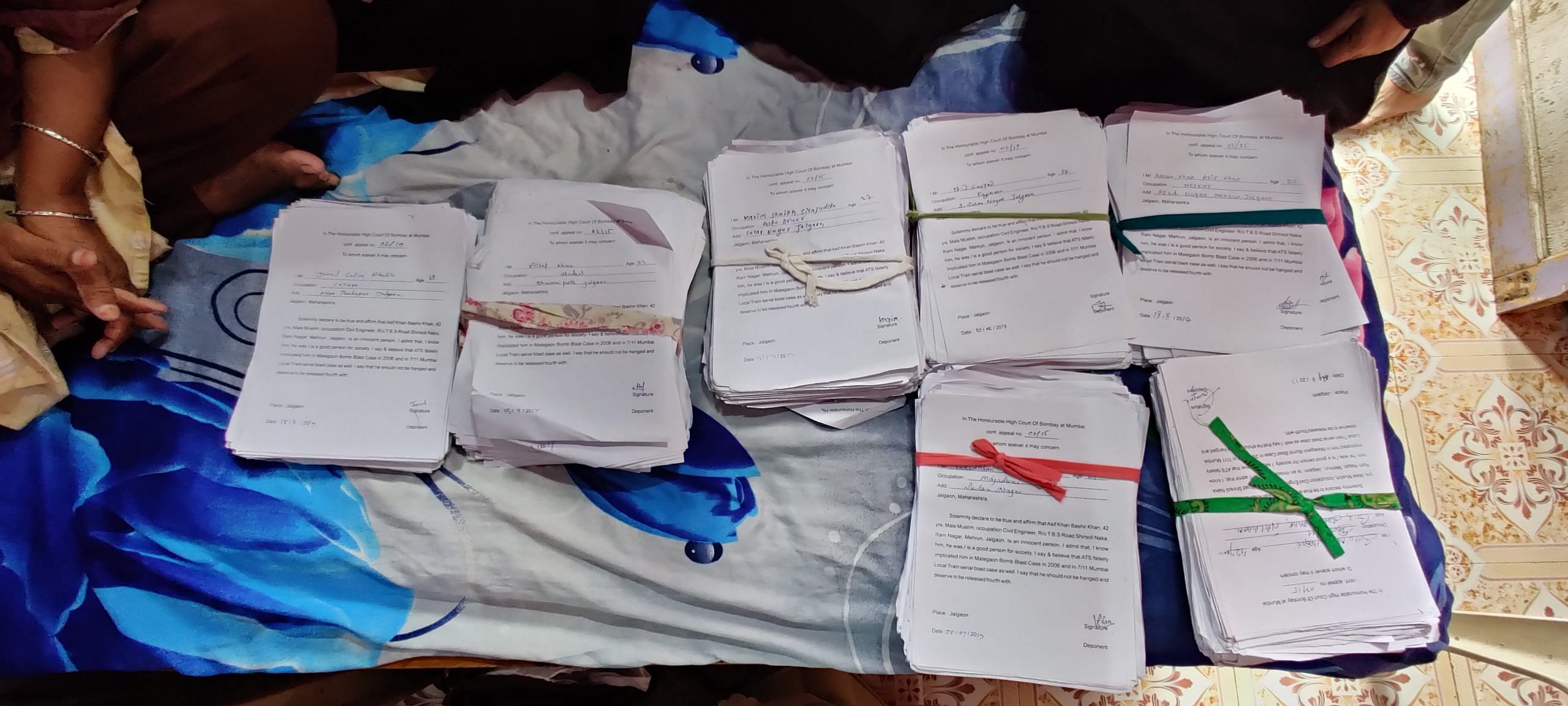

Asif’s cousin Anis Ahmed has amped up his efforts for his release, trying to drum up support within his basti in Jalgaon. He refuses to give up hope, and has collected over 5,000 signatures–all of them attesting to Asif being “a good person for society”, and pleading that he should not be hanged.

As for Jeevak, his younger brother Rahul has thrown an invisibility cloak on the ‘episode’. Rahul was studying in an engineering college when his brother was arrested. Neither his college friends nor his colleagues in his new job know about his brother. However, he was forced to come clean when he made a profile for himself on Shadi.com.

At 30, he started looking for a “life partner”, but the death penalty verdict has made his quest for a wife all the more difficult. Every time he tells one of his potential matches about his brother, he is rejected.

“He didn’t tell us everything, just told us that he won’t marry now. But he cried in front of his sister,” his mother said.

Last year, Rahul gave up on marriage and adopted a dog instead. “He introduces the dog as his son, and us as the dog’s grandparents,” she adds with a dry laugh.

(Edited by Prashant)