New Delhi: The evidence was damning, according to a bench of the Madhya Pradesh High Court — not against the accused in the rape and murder case of a 7-year-old girl, but against the investigators.

A video produced as evidence in the case was nothing but a “story” scripted and filmed by the investigating officer, except that he was “not a good director” and “committed material mistakes”, the court said in a September 2021 judgment.

The allegedly dubious police video and other shortcomings in the investigation led the HC to acquit accused Ravi Toli, who had been sentenced to death in 2019 by a sessions court in Vidisha.

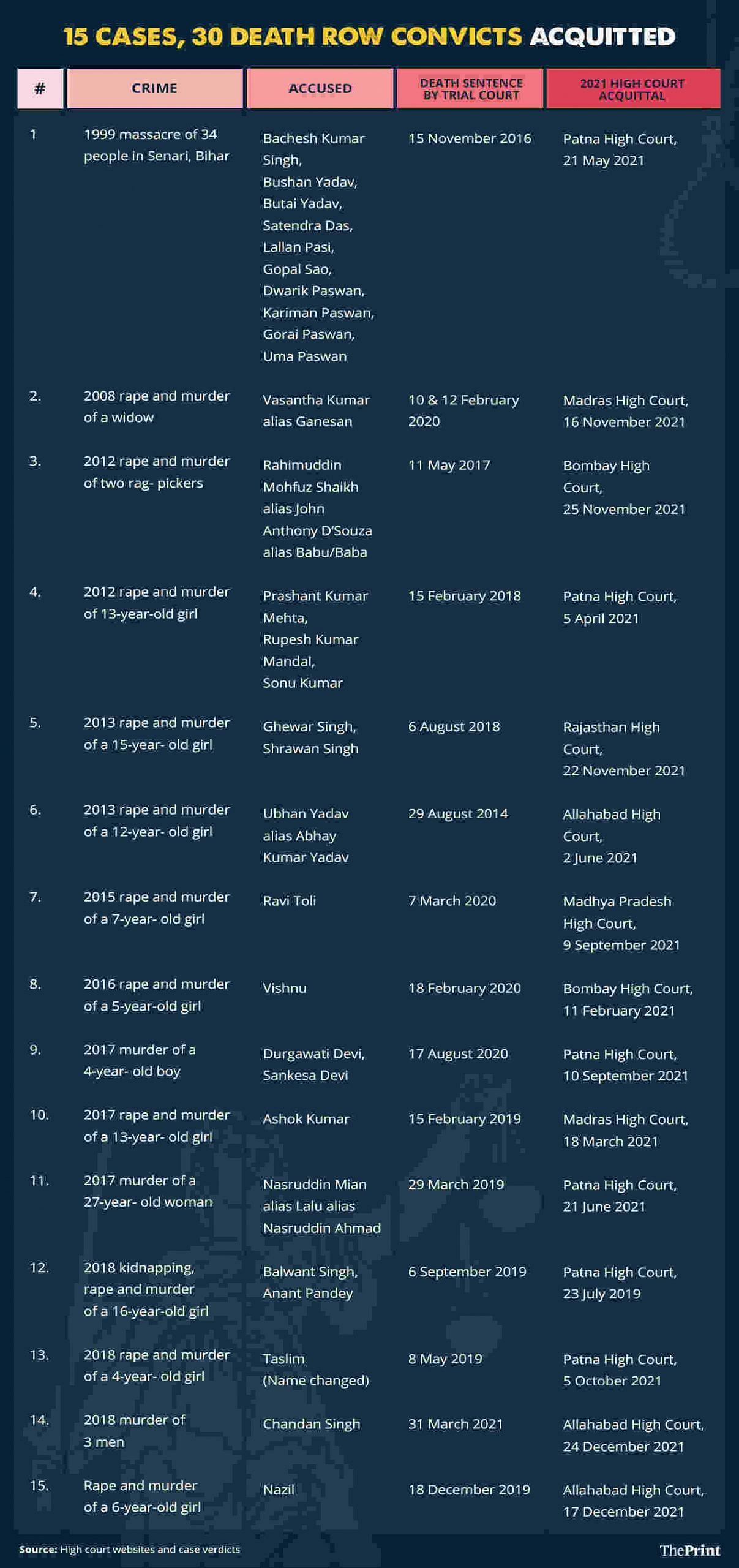

This was just one among 15 judgments that six high courts passed last year, acquitting a total of 30 convicts who had been sentenced to death earlier by lower courts.

These 15 judgments included 11 rape cases (among which nine involved minor girls), a 2018 triple murder in Mathura, and the 1999 Senari massacre allegedly perpetrated by Maoist cadres in central Bihar. In at least three of these cases, the high court also directed action to be initiated against erring investigating officers.

So far, at least four of these high court verdicts have been challenged in the Supreme Court.

ThePrint delved into each of these high court verdicts, which together paint an indicting picture of the criminal justice system in India. The 15 judgments, comprising more than 900 pages together, are rife with allegations of doctored evidence, manufactured FIRs, coached witnesses, missing forensic samples that could have cemented a conviction, prosecution malpractices, lack of proper legal aid, and failures to use appropriate technology.

Also Read: 65% death sentences by trial courts in 2020 involved sexual offences, study reveals

‘Film story directed by the investigating officer’

On 24 October 2015, a 7-year-old girl was kidnapped from a temple outside Bhopal railway station. A day later, her body was found 60 kilometres away in a well in the city of Vidisha in Madhya Pradesh. A month later, the police arrested Ravi Toli for the crime and a sessions court sentenced him to death in March 2020.

But, what seemed to be an open-and-shut case masked some murky details, according to the MP High Court.

Various video recordings were part of the evidence, including of Toli ostensibly confessing to the crime and pointing to the site of the rape. Another recording showed the recovery of Toli’s pants, shirt, and underwear from his house — it is this video that the MP High Court described as a film scripted by investigating officer Sanjeev Chouksey.

The court further alleged that the police tried to “create false evidence” and presented witnesses who were “tutored, unreliable and untrustworthy”. Another witness was found to have given “parrot-like details of the incident”.

In its verdict on 9 September 2021, the MP High Court not only acquitted Toli but also called for the prosecution of two policemen, Chouksey and S.N.S. Solanki, as well as seven witnesses, for giving false evidence.

In this case, the Madhya Pradesh government as well as Chouksey challenged the MP High Court verdict in the Supreme Court which stayed the prosecution of the police officer and witnesses in October last year. Nevertheless, the Madhya Pradesh HC had raised questions that exposed glaring loopholes in the prosecution’s case.

Former Supreme Court judge, Justice MB Lokur, told ThePrint that the prosecution “must be penalised” for producing tutored witnesses.

“It is not enough for the courts to pass what are referred to as scathing observations. They don’t seem to have any effect at all. It is also not enough to say that action should be taken against the investigating officer. The courts must ensure that punitive action is taken, and not merely a transfer from one police station to another, which serves absolutely no purpose,” Justice Lokur added.

Senior advocate Rebecca John, who is a leading criminal lawyer, also told ThePrint that prosecuting agencies are “rarely held accountable for fabricating evidence and putting innocent persons on trial”.

While the recent acquittals by high courts were the outcome of close scrutiny of cases, John said that the accused had already paid a heavy price.

“These cases ended in acquittal but not before the accused suffered long periods of incarceration, with the trial court imposing the death penalty despite the shoddiness of the investigation and unreliability of the prosecution case,” she said, adding that the “sword of the death penalty” hanging over them often had serious mental health, social, and financial repercussions on convicts.

‘Encounter’ arrest, media pressure, ‘manufactured’ FIR

In June 2019, a 6-year-old’s “mummified body”, with her organs missing, was found in a semi-built house in Rampur, Uttar Pradesh, a month-and-a-half after she went missing. Just an hour later, the police arrested a suspect called Mohammed Nazil, but not before shooting him in both knees during an “encounter”. The accused claimed that the police had shot him at close range to get a confession.

A few months later, Nazil was sentenced to death by a fast-track POCSO court in Rampur, but the Allahabad High Court overturned his conviction last year.

The HC declined to comment on the “genuineness of the encounter” and said it was a matter for another trial, but acquitted Nazil, observing that “the police might have been under pressure to show good work because media persons had arrived at the spot when the body was recovered”.

In another judgment about the alleged “sacrificial killing” of a 4-year-old boy, in which two women had been awarded capital punishment in 2020, the Patna High Court concluded that the convictions did not hold good since the FIR had been “manufactured… after due deliberation and consultation”. The HC also noted that the prosecution’s evidence was “beset with contradictions, embellishments and insufficiencies”.

Similarly, the Rajasthan High Court acquitted two death convicts in the 2018 murder and alleged rape of a 15-year-old girl, noting that the prosecuting officer Najeem Ali was “highly tainted” in the way he had conducted the investigation and that the prosecution witnesses were “speaking blatant lies”.

Also Read: Do you have a ‘right to be forgotten’? Here’s what it means and how Indian courts view it

Missing evidence, scene of crime not inspected

Most of the 15 HC judgments highlighted grave lapses in investigation.

In the case of the 2016 murder and rape of a 5-year-old girl, whose body was found in a well four days after she went missing, the Aurangabad bench of the Bombay High Court found that a vital piece of evidence — a nylon rope that was used to strangulate the victim — had gone missing.

The rope found around the child’s neck was sent to a forensic science laboratory to match it with the rope found at the house of the suspect Vishnu Gore. However, on enquiry, the HC was told that the neither the rope nor the forensic report on it could now be traced.

“We are indeed disturbed by the manner in which the prosecution has investigated the crime, collected evidence and conducted the trial in a most insensitive manner,” the verdict said.

The court also rued that “an order of acquittal at our unfortunate hands” was necessary “only because the prosecution has not collected evidence” and “not even taken efforts to get a result from the Forensic Science Laboratory…” The court then directed action against those responsible for the lack of this forensic report.

The Patna High Court expressed similar disgust over the “casual” investigation of a 2018 murder and alleged rape of a 16-year-old girl. Noting that the police had not even inspected the scene of crime — a marriage hall — the court said the prosecution had “miserably failed” to prove its case against the two convicts.

The HC further observed that the accused’s confession was formally recorded 12 days after the body was recovered and that there were “glaring inconsistencies in the evidence of witnesses examined during trial”.

In the case of rape and murder of a 13-year-old girl in July 2017, the Madras High Court found that “an important piece of evidence which exonerates the appellant lock, stock and barrel, has been concealed by the prosecution”. This evidence was blood found on the floor at the place of the incident. DNA profiling of this blood swab found that while it belonged to a male, it did not match with the accused person’s DNA.

The two reports were placed before the HC by the additional public prosecutor, but weren’t presented to the trial court. Observing that it was “saddened” by the fact that the probe was conducted “shabbily”, the court directed the state government to conduct an inquiry into “the lapses in the investigation of the case”.

Justice Lokur told ThePrint that “doctoring evidence or not disclosing exculpatory evidence impacts the right to liberty of an accused person, in clear violation of article 21 of the Constitution.”

“Should such a violation be accepted by the courts?” he asked.

No DNA test, investigations by tractor light

Several high court verdicts hinted at frustration over the lack of a scientific approach to investigations.

The Allahabad High Court, in its judgment overturning the conviction for the 2013 rape and murder of a 12-year-old girl, said the investigating officer “committed a blunder” by not requesting a DNA test of physical evidence even though samples were sent for a pathological examination.

The HC criticised the “casual” manner in which the investigation was conducted too. According to court records, the victim’s body was found under a jamun tree in a grove. The police were informed at around 9 pm, and the station house officer and his team reached the spot about an hour later. They apparently conducted their inspections at the site until nearly midnight, but only in the “light of seven Petromax and head light of one tractor”.

In another June 2018 case of three dead bodies found at three different places in a village called Nagla Bharau in Mathura, the Allahabad High Court lamented the lack of technology employed in the investigation.

The three murders were assumed to have been committed by the same person, even though the entry wounds of the bullet injuries were of different dimensions. A ballistics report by an expert also indicated that two bullets recovered from two of the victims could neither be connected with the weapon recovered from the accused nor ascertained to have been fired from a single gun.

Despite the lack of conclusive evidence, one Chandan Singh was linked to all three murders and sentenced to death in March last year. The HC set aside his conviction and rapped the police for its “shoddy” probe, including its failure to inspect call detail records.

‘Example of how to not write a judgment’

Some HC verdicts expressed their ire not just on investigators but also the trial courts for their assessment of evidence (or lack thereof) and even the language they used.

For instance, setting aside the conviction of a man who allegedly murdered his wife for dowry in 2017, the Patna High Court observed that the trial court’s verdict in that case was an “example of how not to write a judgment”.

One of the offending parts of the trial court judgment was its description of the accused as a “vaishi darinda (savage predator)”. The HC suggested that such language was problematic since “judges must make a dispassionate assessment of evidence and… not be swayed by the horror of crime and the character of the person”.

In the case of the murder and alleged rape of a 4-year-old girl in 2018, the Patna High Court found that the death row convict would have been 17 years old when the crime was committed. The trial court, however, had rejected the claim of juvenility, noting that the accused had first disclosed his age as being between 19 and 20 years, and that this seemed accurate on the basis of “physical appearance”.

The HC noted that the trial court’s approach towards ascertaining juvenility was “erroneous”, and opined that the order was passed in an “arbitrary and fanciful manner”. The accused was acquitted after the evidence against him was also found to be “circumstantial” and insufficient.

Lack of legal aid

A lack of effective legal aid provided to the accused contributed to the acquittals in at least two of the 15 judgments.

In a 53-page-long verdict, the Allahabad High Court acquitted a man accused of raping and murdering a 12-year-old girl in 2013,noting, among other things, that the “legal aid provided to the accused-appellant by the trial court was not real and effective”.

An amicus curiae (friend of the court/counsel) was appointed to represent the accused, but only on the same day that the charges were framed. This meant that the counsel had no time to place his submissions about the evidence under Section 227 of the CrPC, which allows the court to discharge an accused if it feels that there isn’t sufficient ground to proceed with a trial.

In a 2012 case of alleged sexual assault on two homeless ragpickers and the murder of one, the Bombay High Court overturned the death sentence on Rahimuddin Mohfuz Shaikh alias John Anthony D’Souza alias Babu alias Baba, asserting that “…the trial was conducted in a casual manner without ascertaining whether the legal aid provided to the accused was competent and whether the trial was just and fair in a capital punishment case”. The lawyer in the case had been changed several times.

A seeming mix-up in the test identification parade and other irregularities also led the court to speculate that there was some “doubt whether John Anthony D’Souza and Rahimuddin Shaikh are two different persons or one and the same person”.

‘A shocking state of affairs’

According to Justice Lokur, the recent death row acquittals reveal a “shocking state of affairs”, reinforcing the need for systematic changes.

“It seems that the police and the prosecution are only interested in getting a conviction so that the number of successes increases and improves their record. That can hardly be a reason for depriving anybody of liberty, and, in cases where death penalty is awarded, of their life,” he said.

Justice Lokur added that there was a dire need for “positive and concrete action and not cosmetic or ad hoc changes”.

Senior advocate Rebecca John also emphasised that acquittals do not usually solve the problems of convicts, who are let off without any compensation or even any assistance for their re-integration into society.

“The state takes no responsibility for the rehabilitation of these persons once they are released from jail. Although superior courts pass judgements of acquittal in these cases, they rarely hold the investigating agencies to account and almost never direct compensation to be paid to these persons,” John said.

However, what the acquittals do make clear, John said, is how flawed the death penalty is. “[The acquittals] substantiate the call for the abolition of capital punishment from our statute books.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

Also Read: Gangraped in teens, visiting courts as grandmothers: 1992 Ajmer horror is an open wound