Ajmer: A gangrape survivor’s anger tore through the old, yellowing POCSO courtroom in Rajasthan’s Ajmer last December. “Why are you still calling me to court again and again? It has been 30 years,” she shouted at the judge, lawyers, and the accused present in the court. “I am now a grandmother, leave me alone.”

The court was stunned into silence.

“We have families. What do we tell them?” she raged.

Her words made headlines in the local edition of Dainik Bhaskar. The infamous gangrape case of Rajasthan from 1992, referred to as the “Ajmer blackmail kaand (scandal)”, is an open wound even today, resisting cure or closure for the survivors.

Long before the Delhi Public School (DPS) ‘MMS scandal’ in 2004, this was a case of multiple young women being gangraped and blackmailed into submission and silence with video recordings and photos. The Ajmer gangrape case was born out of a toxic mix of political patronage, religious reach, impunity and small-town glamour — and had it not been for an intrepid city crime reporter, it may never have reached the courts.

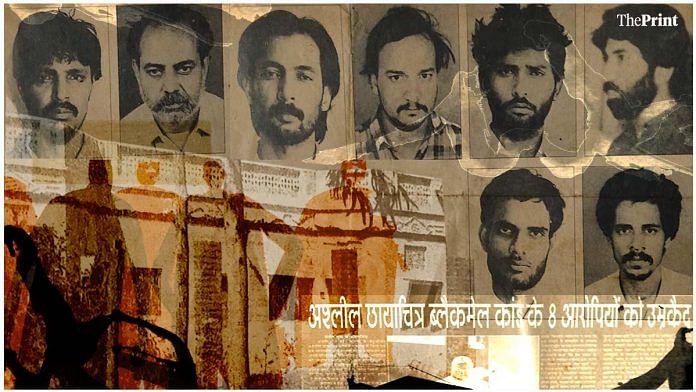

Everyone in Ajmer knew who the accused were — the famous Chishty duo, Farooq and Nafis, who belonged to the extended family associated with the Ajmer Sharif Dargah, and their gang of pals. These men had trapped scores of young school-going girls with threats and blackmail for months and gangraped them. A photo colour lab printed the nude photographs of the women and helped circulate them.

When the story broke, religious tensions rose in Ajmer and the city even shut down. But, not many knew who the women were and where they disappeared after their cases exploded in public debate.

The local media called the women “IAS-IPS ki betiyan (daughters of IAS and IPS officers)” but they were no elites. Many came from modest, middle-class families of government employees, among whom several left Ajmer in the wake of the uproar.

Also Read: Sex traps, secret videos, squabbling IPS officers – inside story of MP blackmail racket

‘Every time they see a policeman, they get terrified’

The police records mention the rape survivors’ first names and vague government colony addresses from which they moved out long ago. School students back then, the gangrape survivors have since moved to different cities with their partners and children and grandchildren, making it nearly impossible for the police to keep track.

Over the decades, the courts summoned the survivors every time an accused surrendered or was arrested. Every time a trial started, policemen landed at the women’s houses in different parts of the state to deliver the summons.

Lawyers say that under Section 273 of the Criminal Procedure Code, the court has to record the survivor’s testimony in the presence of the accused — a process that ends up re-traumatising the women.

Even the police are frustrated. “How many times will we drag them to court? On phone calls, they abuse us. Every time they see a policeman at their doors, they get terrified,” Dalbeer Singh, the station house office (SHO) of Dargah Police Station, said.

For about a year, Singh has been assigned the job of delivering the summons and bringing the survivors to court. He described it as “one hell of a task”.

“One family said that their daughter died. Another family sent a lawyer to threaten me. At least three victims tried to kill themselves after recording their statements in court,” Singh added.

Since the trial began in September 1992, the police have filed six chargesheets, naming 18 accused (up from eight initially) and more than 145 witnesses. The case has spanned 12 public prosecutors, over 30 SHOs, dozens of SPs, DIGs, DGPs, and five changes of government in Rajasthan. The Ajmer police always suspected that more than 100 teens were exploited but only 16 victims recorded their statements during the primary investigation. Most of them eventually turned hostile.

The case has moved from the district court to the Rajasthan High Court, Supreme Court, Fast Track Court, Women Atrocities Court, and is currently in Ajmer’s POCSO court.

Also read: This 12-year-old was abducted, married to 52-yr-old. Her rescue exposed ‘child bride’ racket

The men who lorded over Ajmer

Ajmer today bustles with lake-view restaurants, budget hotels, and markets. But in the early 1990s, the holy city had only two go-to restaurants, Elite and Honey Dew, for the young students of Sophia School and Savitri School.

At the time, these hangout spots were still quite a novelty. Both were located near the railway station, which was better connected than ever before to the rest of the country thanks to a network of new trains, and it was the start of the heady Manmohan Singh era of economic boom and hope in India.

The new rich were those who could flaunt their cars, dish TV connection, along with their old money trappings like Royal Enfield, Yezdi, and Java bikes. And the influential Khadims — the extended family of caretakers of the Ajmer Sharif Dargah back then — had it all.

The young men of the family were like local celebrities. They drove around in their open jeep, Ambassador and Fiat cars. They visited the sole gym in the city and styled themselves after Sanjay Dutt, then all the craze in small-town India, with long hair and chains around their neck.

Along with swagger, these men had money, social influence, and political power. Both Farooq and Nafis were top leaders of the Youth Congress in Ajmer and believed to have friends in high places.

“All this clout helped them. I remember one incident where the two of them, on their jeep, went to Elite where some schoolgirls were sitting. One of them called the (restaurant) manager and asked him to distribute ice cream to everyone as it was the birthday of one of their friends. It may seem filmy, but during that time, it could leave anyone spellbound,” Santosh Gupta, a crime reporter at that time for Dainik Navajyoti, recalled.

He added: “Every crime reporter closely followed the gang because with great power comes great crime stories.”

Grooming, gangrape, blackmail

Whether it was a “great crime story” or not, court documents and the statements of those associated with the case paint a sordid picture of the baiting, sexual exploitation, and blackmail that unfolded behind the gates of an Ajmer bungalow, a farmhouse, and a poultry farm in the early ’90s.

Many women withdrew their testimonies and it is likely that some never came forward, but the known timeline of events starts in 1990.

At some point that year, an ambitious young girl called Gita*, a Class 12 student of Savitri School, decided she wanted to join the Congress party. Luck seemed to be on her side when an acquaintance called Ajay* told her he knew just the people she should talk to: Nafis and Farooq Chishty.

“In those days, gas connections used to be a big deal. Gita would tell Ajay about wanting a gas connection and also about her wish to join the Congress, and he took advantage of that. He introduced her to Nafis and Farooq Chishty, telling her they were good people,” Virender Singh Rathod, currently the prosecution’s lawyer, said.

A 2003 Supreme Court judgment in the case details Gita’s testimony about how she was groomed, sexually assaulted, and then blackmailed into bringing more young women to the Chishty duo and their friends.

According to Gita, Nafis and Farooq met her a few times when she was with Ajay, once rolling up in their Maruti van as she walked to the bus stand. They assured her they would set her up with an assignment in the Congress.

Their associate Sayed Anwar Chishty later gave her forms to fill and told her she needed to submit a passport-sized photograph.

Everything seemed above board, so she was not worried when one day Nafis and Farooq intercepted her in their van while she was on her way to school and offered her a lift. She accepted, but instead of taking her to school, the men brought her to a farmhouse.

In her testimony, Gita said she believed that the purpose of the detour was to discuss her entry into the Congress, but the moment she was alone with Nafis, he pounced on her and sexually assaulted her, threatening to kill her if she did not do as he said. A few days later, Gita testified, he accosted her again and repeated that she would regret it if she told anyone about the assault.

This was only the beginning. The men coerced Gita into introducing them to other girls, sometimes as her “brothers”, and to build their trust so that they would willingly attend “parties” at the farmhouse or Farooq’s bungalow on Foy Sagar Road. Many of these women were sexually assaulted by one or several men. The rapists usually took photos of the rapes since shame and blackmail were the most reliable guarantees of the survivors’ silence.

“The media sensationalised the case by saying these were the daughters of IAS-IPS officers. One was the daughter of a Rajasthan civil service officer and another of an agriculture officer,” Dalbeer Singh said.

Disturbingly, Gita testified that in the early days of the gang-rape spree, she and another victim, Krishnabala* did approach a police constable who also introduced them to an officer working in the special branch of the Ajmer police. They promised to help retrieve the blackmail photos, but the women soon got threatening calls asking them why they had contacted the police. Gita claimed that the constable once asked her and Krishnabala to accompany him to recover the photos from the Dargah area. While the policeman stood at a distance, one of the gang members, Moijullah aka Puttan Allahabadi, sauntered up, and said, cryptically, that “the game which they were playing was a game they had played long back”. The photos were not returned.

“Dargah par aane wale log unke hath choomte the (People coming to the Dargah used to kiss the hands of the Chishty family). They used this religious power to get political influence. SPs to SHOs would call them to negotiate over FIRs or issue appeals. No one could say no to them,” journalist Santosh Gupta recalled.

Meanwhile, the women’s worst fears came true. Some employees of the photo lab where the sexual assault images were printed circulated the pictures, further perpetuating the abuse. If there was any upside at all, it was that this is what led to the case coming into public consciousness.

According to Santosh Gupta, a reel developer called Purshottam bragged about the sexual exploitation photos when he saw his neighbour Devendra Jain looking at a pornographic magazine. Purshottam had apparently scoffed: “This is nothing. I’ll show you the real stuff.”

The “real stuff” alarmed Devendra who made copies of the pictures and sent them out to the Dainik Navajyoti and the local Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP) group. The VHP workers passed on the pictures to the police, which began an inquiry.

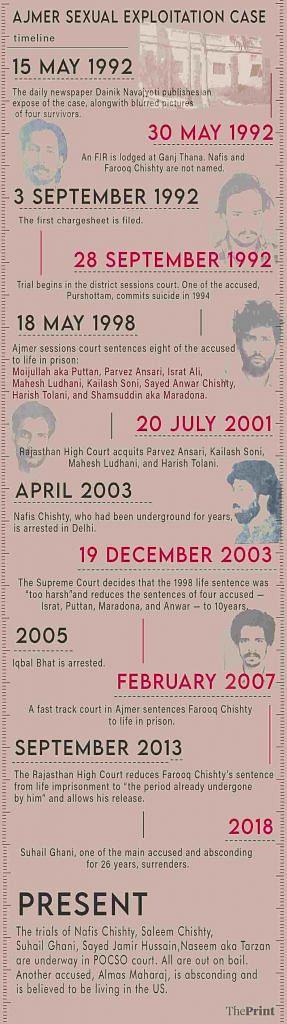

Meanwhile, on 21 April 1992, Gupta wrote his first Dainik Navajyoti report about the sexual exploitation. However, it did not make much of a stir until the paper published its second report, this time with blurred pictures of the unclothed survivors. This story came out on 15 May 1992 and caused an uproar almost immediately. All of Ajmer shut down on 18 May because of public anger over the case.

On 27 May, the police issued National Security Act (NSA) warrants against some of the accused, and three days later, then-North Ajmer deputy superintendent of police (DSP) Hari Prasad Sharma lodged an FIR at Ganj Police Station. Then-SP CID-Crime Branch, N.K. Patni was sent from Jaipur to Ajmer, to investigate.

Speaking to ThePrint, Patni, who is retired now, said that this high-profile case came at a time when communal tensions were rising in India. L.K. Advani’s rath yatra had taken place a couple of years earlier and it was just months before the Babri Masjid’s demolition.

“This was a big concern back then — how to not communalise the matter as the main accused were Muslims and the majority of the victims were Hindus. The lab technicians and a few other accused were Hindus,” Patni said.

He recalled recording the statements of seven witnesses during the investigation, including an eyewitness who went on to testify in court. “I went to her house in civils. I had to convince her that she did not do anything wrong. After a lot of counselling, she recorded her statements,” Patni said.

In September 1992, Patni filed the first chargesheet, which ran into 250 pages, listing 128 eyewitnesses and 63 pieces of evidence. The district sessions court started the trial on 28 September.

Trials, and then more trials

Since 1992, the Ajmer rape case has followed a convoluted and lengthy legal trajectory, with several different trials, appeals, and some acquittals.

Eighteen people were named as the accused overall, out of which one, Purshottam, died by suicide in 1994. The first eight suspects to go to trial were sentenced to life in prison by the district sessions court in 1998, but the Rajasthan High Court acquitted four in 2001 and the Supreme Court reduced the sentences of the rest to ten years in 2003.

The rest of the suspects were arrested and sent to trial at different points in time over the next few decades.

Farooq Chishty claimed he was mentally incompetent to stand trial but in 2007, a fast-track court sentenced him to life. In 2013, the Rajasthan High Court deemed he had served enough time and released him.

Nafis Chishty, a history-sheeter who was also wanted in connection with drug peddling cases, was absconding until 2003, when the Delhi Police found him wearing a burqa to escape detection. Another suspect, Iqbal Bhat, evaded arrest until 2005, while Suhail Ghani Chishty surrendered in 2018.

With every such development, the survivors who were still willing or able to testify were dragged back to court.

Currently, six of the accused — Nafis Chishty, Iqbal Bhat, Saleem Chishty, Sayed Jamir Hussain, Naseem aka Tarzan, and Suhail Ghani — are undergoing trial in POCSO court, but they are all out on bail. One more suspect, Almas Maharaj, was never caught and is believed to be living in the US. An arrest warrant and red corner notice have been issued against him.

“Some accused were given life sentences, but a few police officials and special prosecutors weakened the case over the years,” N.K. Patni, who filed the first chargesheet, said.

Also Read: 1-yr since Hathras ‘gang rape’: Caste divide is deeper, memories don’t fade, drama in court

‘People still kiss the duo’s hands’

Today, Nafis and Farooq Chishty are leading a privileged life in Ajmer and are frequent visitors to Dargah Sharif, where some of the faithful still ritualistically kiss their hands, Gupta said.

Nafis, according to Dalbeer Singh, is a “habitual criminal” but this has not affected his social standing. “In 2003, he was caught with smack worth Rs 24 crore. There are also cases of abduction, sexual harassment, illegal weapons, and gambling against him,” the SHO said.

Since his release, people in the city have frowned upon how Farooq is treated like a respected elder of the prestigious Khadim family.

When ThePrint tried to contact Farooq Chishty, one of his close family members said that the matter was over and there was no need to look back.

ThePrint also called Nafis Chishty, who said he had nothing to do with the case. “My name was wrongly framed. There are seven or eight people called Nafis in the city,” he said before disconnecting the line.

Away from the Dargah area, where members of the Chishty clan live in large, well-kept houses, leaving the past behind has been more difficult.

Savitri School, its outer walls featuring slightly dated paintings of women icons like Madhuri Dixit, Kalpana Chawla, and Indira Gandhi, is still functional but its hostel has been shut since 1992. Sophia School, too, no longer runs its boarding facility for girls. Neither school has quite recovered its reputation.

For years, the stigma of the “scandal”, at least in the eyes of Ajmer’s more conservative sections, tainted all young women in the city, whether or not they had crossed paths with the gang.

“No one wanted to marry girls from Ajmer. I used to get so many unwanted visitors in the ’90s. People would tell me about upcoming weddings and then show me a picture of the bride. They would ask me to tell them whether or not she was ‘one of them’,” Gupta recalled, adding that in the months after the story broke, if a girl died by suicide, she was assumed to have been a victim of the gang.

For the survivors, the aftermath was harrowing, especially for the few who decided to testify in court.

One such survivor was Krishnabala, whose statements contributed to several convictions. The Rajasthan High Court’s 2001 judgment says she identified Farooq, Israt Ali, Shamsuddin aka Maradona, and Puttan in court. It also details her testimony about how she was gangraped and blackmailed by these men as well as Suhail Ghani and Nafis. Then, in 2005, Krishnabala disappeared.

“I am bothered by the fact that Krishnabala is yet to be traced. She is the strongest among all the eyewitnesses and could bring closure to many,” Dalbeer said.

But, there is still hope. Sushma*, a victim who turned hostile in three trials, decided in 2020 that she would speak up in court after all. She still lives in Ajmer, in a small house facing a narrow alley where ThePrint met her.

Rs 200 for lipstick and powder

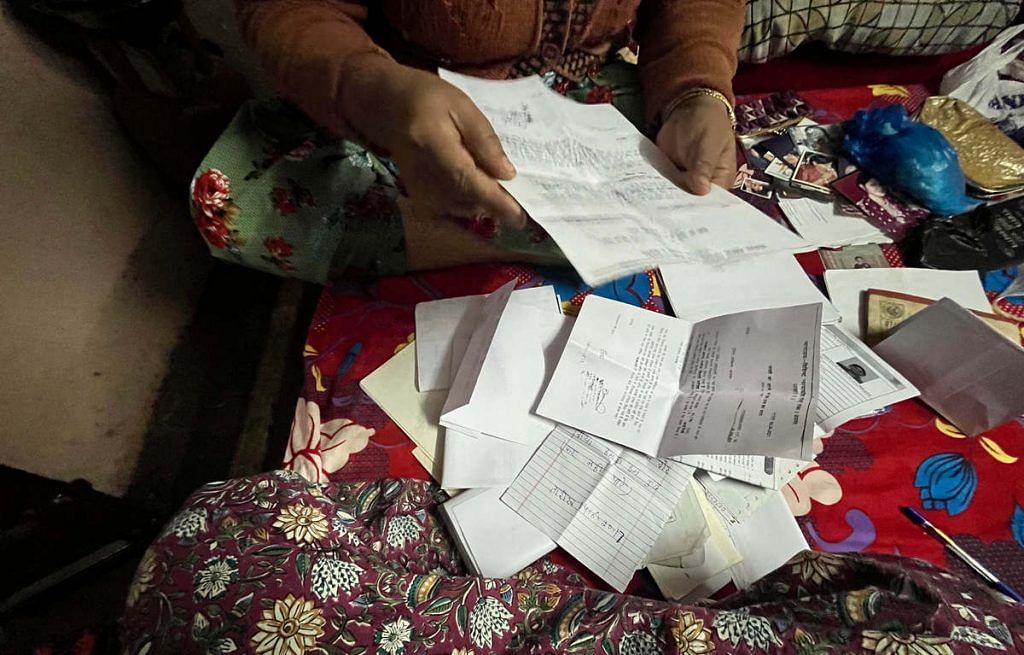

Sushma’s house is small but colourfully decorated with photographs and knick-knacks. Dressed in a green floral-printed salwar kameez and with her hair tied into a business-like bun, the 50-year-old said she was ready to talk after years of trying to suppress her trauma.

“No one from (the) media ever reached out to me. I tried to bury this incident in my memories,” Sushma said, bringing out a sheaf of photographs that show a tall, fair-skinned girl with shining eyes. “Look at my hair,” she said. “It used to be so thick.”

But, even before she fell into the clutches of the gang, Sushma was particularly vulnerable. The youngest child of six in a poor family, she suffered from mental health issues even as a child and dropped out of school when she was in Class 8.

According to Sushma, her link to the gang was an acquaintance called Kailash Soni. He lured her to a deserted building, raped her, and then invited seven or eight other men to also sexually assault her, she said. Sushma was only 18 years old at the time.

“I was too naive to understand what they did to me. They took turns to rape me. One would rape me, while another would click pictures as he waited for his turn,” she said.

Nude pictures of Sushma as well as the dilapidated building were part of the evidence produced in some of the trials.

“After doing all this to me, Nafis gave me Rs 200 and told me to buy some lipstick and powder,” Sushma said, anger finally breaking through her sanguine surface.

Thinking about the blackmail photos made her anxious, she said, and repeatedly asked for reassurance that a picture of her face would not be published. “I have two nieces. They still don’t know what happened to me,” Sushma explained.

Sushma was one of the few survivors who was medically examined in 1992, and was expected to testify, but her life was unravelling.

“I got pregnant. My mother tried everything [to induce a miscarriage] but wo kehte hain na ki haraam ka baccha kabhi girta nahin toh ye bhi nahin gira (as they say, a devil’s child can’t be miscarried, and so it was the case with this one). He was born dead, though,” she said.

A year later, Sushma said, a rickshaw-puller raped her and kept her captive in his house for 25 days. She got pregnant again and this time delivered a baby boy who was adopted by a distant relative. “They kept him for two or three months, and then he died too,” Sushma said.

By now, Sushma’s mental health was at breaking point and she spent hours wandering around and sitting at mosques and temples. Her family took her to faith-healers and even for electroconvulsive therapy, but nothing helped much. “My life has been hell,” she said simply.

When she was 22, her family got her married to a fruit seller in another city. On their wedding night, she confided in him about her ordeal. He did not react then, but four days later he dropped her at her parents’ home and never returned. “My husband abandoned me while I still had henna on my hands,” Sushma said.

Six years later, when she was 28, she met another man and later had a son with him. Her second husband divorced her in 2010, she said, but she never stopped loving him. He died three months ago, but she got two rings, inscribed with their initials, made in his honour. “He looked like Anil Kapoor and he knew all about my history,” she said. Her son, Sushma added, is not very close to her since his paternal grandmother always took care of him.

When Sushma was younger, her now-deceased uncle took her to court a few times, but she turned hostile. When asked why, she said: “Nafis and many of the gang live in the same area as my sisters’. I used to pass the same streets. They threatened me.”

However, when a policeman from Dargah station found Sushma in 2020 and handed her a court summons, she agreed to testify. She was nervous but felt reassured when the policeman accompanied her to the court. “In 2020, Nafis and the rest did not know about my hearing, fortunately.”

Also Read: ‘For fun, releasing frustration’: Clubhouse users who made rape threats, slurs against Muslims

A policeman’s chase

When Dalbeer Singh first heard about the Ajmer rape case, he was a young boy growing up in a small village in Bharatpur. “Everyone used to talk about it,” he said, and so it stuck in his memory. He joined the Rajasthan Police in 2005, but it wasn’t until he got a call in 2020 to help bring in more survivors and witnesses to testify that he realised that the case was not over yet.

“I was shocked that this case was still undergoing trial… I feel so angry about it, though I felt privileged to do my bit,” he said.

Dalbeer, who recently handed over his duties in this case to another policeman, said he is proud of what he achieved. “For the last 14 years, the police could bring only 58 eyewitnesses. But in this Covid time, I brought 40 more eyewitnesses, including victims,” he said.

However, there were times when the task was more difficult than he had anticipated.

“In one case, the victim’s mother refused to even let her talk. I got a court order to access the mother’s call records and managed to reach the daughter. When I called, she was so angry. She asked, ‘Why after so many years?’ It took dozens of calls and then counselling to get her consent [to testify],” Dalbeer said.

Once when he called the father of a survivor, the elderly man snapped: “We don’t have anything to do with this. She is no more.”

Virender Singh Rathod, the prosecution lawyer, understands the survivors’ frustration and believes that the judiciary, media, and administration let them down.

“They have become dadis and nanis (grandmothers). Are we going to keep calling them and asking them what happened?” he asked.

Yet, there are times when the endeavour to rope in witnesses does not seem so futile.

Nafis, Jameer, Tarzan…

No one expected very much of Sushma when she walked into the POCSO courtroom in 2020, given her history of turning hostile and her mental health struggles. In earlier court appearances, she had refused to recognise her rapists despite photos of the sexual assault and other evidence being shown to her. In 2001, when the Rajasthan High Court acquitted Kailash Soni and Parvez Ansari, the bench noted that “[she] alone could have established the guilt against the appellants…”.

However, this time, Sushma seemed confident and assured as she looked the men in front of her in the eye.

When asked to identify her rapists, she spoke their names, one by one, clearly and loudly: “Nafis, Jameer, Tarzan…”

She hesitated briefly when her eyes moved to the next face, unable to remember his name. Then, she pointed at him and said: “Ye bhaiya bhi the jinhone rape kara (This brother also raped me).” The man in front of her was Suhail Ghani, who had surrendered in 2018.

Rathod said this moment in court gave him goosebumps. “That day, she blasted… even in her 50s, she addressed her rapist as bhaiya (brother). That one line has stuck with me.”

* Names have been changed to protect privacy.

This article has been updated with new source links and attributions.

This is an investigative three-part series on decades-old gang rape cases where ThePrint examines systemic prejudice, implementation of laws, and the women’s lives long after the public gaze veered away from them.