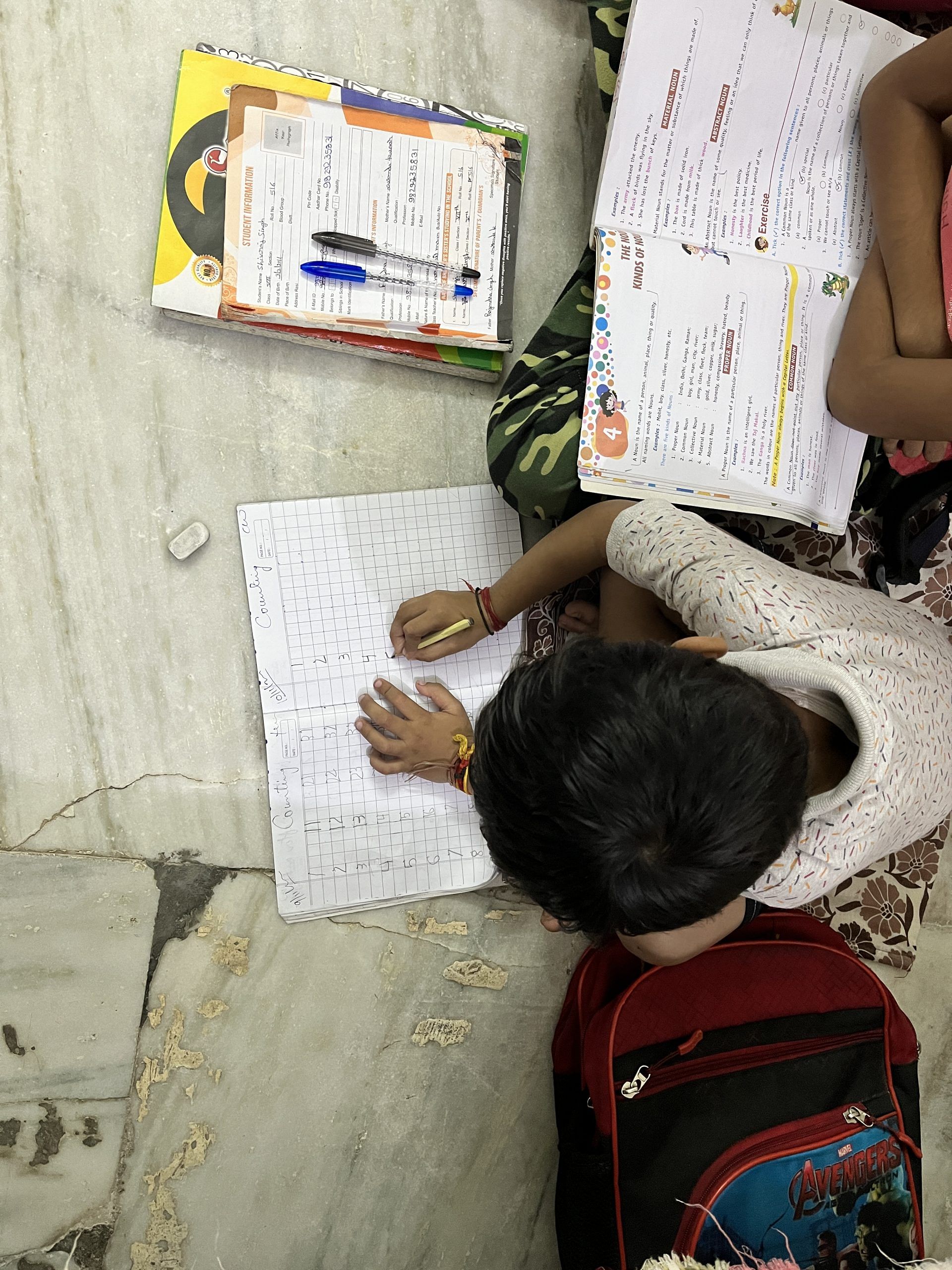

Five-year-old Kanishk can barely count to 30 and gets stuck at ‘Q’ when reciting the English letters. His mother has already decided that he will become a doctor. So, every day, after five hours of classes at a private school in Jaipur, he stuffs 11 books into his red bag and attends two hours of tuition. This gruelling school-plus-tuition epidemic will be his life until he gives the pre-medical National Eligibility cum Entrance Test when he completes class 12. The pace will only get more frenetic—and frantic—with each passing year.

Kanishk isn’t alone. He is part of the mammoth ‘Tuition Republic’, a thriving industry born out of an indifferent rote learning-based school education system, parents’ unreasonable ambitions and a shrinking job market.

From Madhya Pradesh to Maharashtra, Bihar to Kerala, the tuition republic of India with its neighbourhood tutors, teachers moonlighting as tutors, social media edu-influencers and coaching classes has spread its tentacles into the digital world as well. After two years of pandemic interruption, it’s now bigger than ever and is an inescapable part of growing up in urban India. According to the data published by the National Sample Survey in 2016, there are 7.1 crore students enrolled in tuitions.

Psychologists are studying the effect of this prolonged period of lost childhood and stress induced by this rush for a ceaseless tuition race.

“There was a time when tuition classes were temporary solutions. In 2022, they become a lifestyle,” says child psychologist Dr Nimesh Desai. “It starts from the age of five and goes on for the next two decades. When that person becomes a parent, he/she enrols their children in tuition as well,” Dr Desai adds.

For Kanishk’s mother, Priyanka (28), this is the only route to respect and prestige, if not wealth. Her husband barely completed school and earns Rs 10,000-15,000 as a masseur. Now, all her hopes are riding on Kanishk’s tiny shoulders.

“We want our son to have a better life than we have, but there is high level competition these days. If he starts tuitions now, by the time he reaches 9th or 10th standard, he would have adapted to this way of life. He would know that to excel in the competition, he has to go through this rigorous process each day,” says Priyanka.

Also read: IIT mania is costing students quality time at schools. But CBSE, other bodies still sleeping

School, tuition, repeat

The government is banking on the National Education Policy to improve the existing education system and reduce the dependence on tuition teachers and coaching classes. But so far, legislation has done little to stem the growing reach of this parallel industry.

“This is a complete failure of our mainstream education that turned parents towards this market. How do you tell Kanishk’s parents not to send him to tuition at the age of five?” says a senior bureaucrat with the Department of School Education and Literacy, Ministry of Education.

The annual revenue of coaching institutes was a whopping Rs 24,000 crore, according to a 2015 estimate by an expert committee set up by the education ministry (then-Union Human Resource Development ministry). The current market revenue of the coaching industry in India is Rs 58,088 crore, according to Infinium Global Research, a consultancy firm based in Pune. The coaching industry’s growth is projected to reach Rs 1,33,995 crore by 2028.

Educationists and psychologists are alarmed and are calling for a large-scale survey to study the industry, especially at the school level where kindergarten children rely on private tuitions.

Kanishk is the youngest of the 15 students in Poonam Tharwan’s tuition class. He is not even a ‘weak’ student sent for additional tuition. Tharwan says Kanishk is among the more well-behaved students who completes his school homework on time, does his revision and returns home at 5 pm with more tuition homework.

He has to stick to this path for the next 15 years or so. School, tuition, revision, homework. Rinse. Repeat. And then there are coaching centres for competitive exams when he grows up.

Also read: Little known, but much in demand — ‘star’ teachers keep IAS, IPS, IFS coaching industry going

Life in the tuition paradise

At 2 pm on a Monday, the relatively quiet road near Pratap Nagar market erupts into a sea of students when the school bell rings. Groups of children emerge from the gates of MVG Public School, where Kanishk studies, their heavy bags slung on their shoulders.

Some rush straight for tuition. Others head home for a quick lunch or a short break. Kanishk’s cousins, classmates and neighbours all follow a similar routine.

Whether they realise it or not, they’re in the race for a limited number of seats in medical, engineering, law and teaching colleges, or jobs in the civil services, railways, etc.

This year, UPSC 2022 preliminary examination saw more than 11 lakh aspirants competing for 1,011 seats. And more than 18 lakh students attempted NEET for 91,927 MBBS seats in 612 government and private medical colleges across the country.

In the same Pratap Nagar neighbourhood, 37-year-old Neelam Tikkiwal wants her nine-year-old son and two-and-a-half-year-old daughter to be toppers.

“But in his last half-yearly exam, my son got only 35 out of 80. I expected him to score at least 60. This was despite school hours, tuition hours and two hours of revision at home. As a parent, you want to see your child scoring 90 per cent,” says Neelam.

She graduated college through distance learning because of her financial conditions. Her husband, who currently runs an e-Mitra shop, earns around Rs 60,000 a month. “But there are things that, as a middle-class family, we cannot afford. I don’t want my children to miss out on those things when they become adults. With the help of tuition, our children will excel in everything,” she says.

In small towns and villages, it’s almost as if every third household has transformed into a personalised tuition centre. Living rooms have become classrooms and the neighbourhood aunty or the young college graduate have become teachers.

Kanishk’s tuition teacher Tharwan has a slew of degrees—a Bachelors and a Masters in Commerce as well as a Bachelor of Education. But the 30-year-old finds private tutoring more lucrative than most jobs she is qualified for. She has been tutoring for 10 years now, and is a product of this parallel system herself. But unlike the children she teaches today, she enrolled in private tuition classes only in class 12.

“Back in 2012, whoever took science and commerce streams needed tuition,” Tharwan’s tutor Pulkit Jain says. He too needed extra classes when he was a student in Rajasthan University.

Now, however, parents want their children to begin as early as possible in the hope that it will give them an edge. It’s also a matter of keeping up with the Joneses.

In big cities, STEM, coding and Kumon are all the rage. In small towns as well, private tutors or coaching centres that offer coding classes are highly sought after. And e-learning steps in where such tutors or centres aren’t available. Children as young as eight years old are signing up to learn Python. Udemy, White Hat Jr, Coding Ninjas and LeapLearner are hugely popular. Coding Ninjas claims to have ‘transformed’ 50,000 students through its signature courses.

The education system is getting more crowded and competitive, but infrastructure has not kept up. “Parents’ aspirations, children’s aspirations and job opportunities—all these factors make the ecosystem. Exams are the only currency that decides a child’s future. The market is growing as the demand for these institutions is growing,” says Rukmini Banerji, CEO of Pratham Education Foundation.

Also read: More women students now study STEM courses in IITs, NITs & other universities, shows govt data

Growing demand

Parents see tuitions as the only way for their children to edge out competition, escape the family’s social station and ace the jobs game. For teachers, conducting private tuition has evolved into a lucrative business.

“This is an alternative successful career now. If you don’t get through the competitive exams, you end up tutoring students,” says Tharwan who charges each student Rs 1,000 a month.

In Pratap Nagar locality, she is needed more than ever, especially since the pandemic. “Before Covid, I had 10 students. Now there are five more. The demand for home tuitions was impacted during the pandemic but even then, some parents would send their kids because they didn’t have faith in the online system,” she says.

The private tuition market is divided into three segments—group tuitions (personalised setup), private tutoring (exclusive) and coaching centres (competitive).

“We really don’t know when school education became secondary to tuition and coaching,” says Yugank Goyal, associate professor of public policy at FLAME University, Pune.

Working class and lower middle-class families send their children to group tuitions where the monthly fee ranges from Rs 500 to Rs 1,000. The upper middle-class prefer private tutors, most of whom are post graduate university students and scholars. Many charge as high as Rs 4,000-8,000 per month.

The vast majority of the middle-class opt for coaching centres. The sector dominated by giant brands like Byju’s, Allen Career Institute and Resonance come into the picture.

Byju’s, for instance, has more than 4,000 tuition centres across India. Within a year of launching in Jaipur in October 2021, the brand set up six centres in the city. Students from class one to three are taught online, while the rest up to class 10 have to attend offline classes.

“This is where supplementary education becomes complex, competitive and exclusive,” says Banerji, of Pratham Foundation. She underscores the need for a large-scale survey to study this industry, especially at the school level.

“There are many patterns in different locations in India. For example, the number of tuitions in rural Odisha and West Bengal is very high. But in states like Rajasthan and Haryana, there are big private schools. There is no standard operative procedure for tuition culture,” Banerji says citing the 2012 ASER report.

Nearly a decade later, the 2021 ASER report revealed that 40 per cent of school children (aged 5-16) surveyed across 25 states and three union territories were enrolled in private tuition. In 2018, it was 30 per cent. This trend has grown across all states except Kerala. A majority of families opting for private tuition were from lesser privileged classes.

Also read: How Indian schools are failing trans & non-binary teachers — ‘accepted only on the surface’

Tutors vs NEP

Successive governments and Members of Parliament have tried to tackle this “tuition menace” over the years.

Former MP from Uttar Pradesh, Mahendra Mohan had introduced a Private Members’ Bill — The Coaching Centres (Regulation and Control) Bill, 2007— in the Rajya Sabha. “….Coaching centres are playing with the fate of lakhs of students and therefore the time has come to regulate and control their activities,” stated the Bill.

In 2012, then-minister of state for education, D Purandeswari, announced in Parliament that the government would bring a legislation to curb the menace of coaching centres. She called the coaching industry a monster. But the focus was on the high fees they charged students.

Whenever students enrolled in coaching classes died by suicide, state governments have promised to keep tabs on the industry.

In 2015, after a spike in student suicides in the tuition hub of Kota, the Rajasthan government planned to regulate coaching centres. It took four years before a state-level committee was finally constituted to prepare a draft for new legislation. In 2022, there were reports that the government would bring in a law to not only regulate coaching centres but also to safeguard students. A report in The Times of India said there would be provisions against glorifying toppers. So far, no law has been enacted.

To date, Bihar is the only state in India that makes it mandatory for coaching institutes to register themselves under the Bihar Coaching Institute (Control & Regulation) Act, 2010. But its good intentions have been diluted by red tape and “inspector Raj”.

“If the Act had any impact in controlling the growth of the coaching centres, then their number would not have increased to 4,200 in 2022 from 1,700 in 2010. For 10 years, there has been no progress in registration,” says Sudhir Kumar Singh, national secretary of the Coaching Association of Bharat.

It took the violent protests over Railways’ recruitment in January 2022 for coaching centres in Bihar to get their act together. “Some 400 coaching centres got themselves registered after the protests,” Singh adds.

In Kerala, the State Commission for Protection of Child Rights issued a directive to the government—either expand the Kerala Panchayat Raj –Nagarapalika Acts or make new rules to protect the rights of children enrolled in private coaching centres.

“The need of the hour is to acknowledge this sector as an industry and then bring legislation to regulate it. The sector brings revenue and employment and enhances the quality of education. Bureaucrats, MBBS doctors and IITians–all have contributed to this sector in the last 10-15 years,” says Singh.

Senior education officials are banking on the New Education Policy (NEP) to break the stranglehold that private tuition centres have over the education system. One of the objectives of the NEP is to focus on “regular formative assessment for learning rather than the summative assessment that encourages today’s coaching culture”.

“The NEP encourages regional languages in the school syllabus with a focus on the overall development of a child. When we provide such holistic education, the demand for supplementary education will go down. There will be reforms in the curriculum and examination system to correct this,” an official from the education department said.

But Singh says the NEP will only fuel demand for coaching centres. “The child will be required to decide the career trajectory in the 6th grade itself, which will increase the demand for coaching centres,” he says.

Many private tuition teachers and managers of coaching classes say they are being painted unfairly as villains when all they’re doing is make up for the lacuna in the education system. Bigger and more well-known brands and coaching centres are edging out local teachers like Poonam Tharwan, not just in metro cities but in small towns as well.

One major problem is that the school curriculum and its teachers are stuck in the old world. They haven’t been upskilled for the new hyper-competitive era of jobless growth.

“Teachers in higher classes aren’t evolving with time and technology. Young parents, below 35 years of age, feel the need for extra classes for their children as they know from experience how competitive the industry has become,” says a manager employed with Byju’s Jaipur tuition centres, explaining the rising demand.

A decade ago, it was the familiar senior teacher from school who was trusted for giving tuitions. But big private players have captured the market in metros and are now expanding their business to smaller cities across the country. A Byju’s poster in Rajasthan’s Sikar explains the trend.

Also read: Intense anxiety, burnout, entrance exams — education in India needs an overhaul

Weight of parents’ ambitions

Parents more competitive than their children are pushing for extra coaching because they themselves are unable to help with school work. Psychologists say children should not be made to carry the hopes and dreams of their parents.

“Social prestige and parental anxieties and frustration turn education into an unhealthy competition. There have been serious consequences of this. Pitting children against each other can result in loss of self-esteem when they grow up,” Dr Desai warns.

Professor Goyal from FLAME University similarly expressed concern about the child’s all-round growth. “Children could have used those hours being themselves and building human capital. Exams are a test of memory. They evaluate students, not assess them,” he says.

Students are burning out. Fifteen-year-old Rakshit Balhara, a 9th grade student of Mother Divine Public School in New Delhi can’t remember the last time he played football.

“I spend time on social media instead as it does not require me to go physically somewhere,” he said.

A class 12 student from the city’s Sanskriti School dropped out of Aakash Institute when she was in the 10th standard.

“Aakash put a lot of pressure on me, and I had no other option but to leave. The hours per day were extremely tiring,” says the student. She later signed up for a group tuition, which is more personal.

Signs of burnout are clearly visible in Kanishk’s case as well. He dreads going to school and his only friends are his parents’ mobile phones. When he is not studying, he is playing games or watching cartoons on YouTube.

At his tuition, Prakhar, a class 4 student is constantly pitted against Nimesh, a class topper, who is known to be “curious and talkative”.

“I saw Nimesh asking too many questions in online classes. So, I wanted Prakhar to not lack those skills,” says his mother Poonam.

Both Poonam and Priyanka are worried that they are not paying enough attention to their children. Their husbands work overtime and take up extra jobs to pay the tuition fees. Poonam’s attention is divided between Kanishk and his younger sister. So, she’s preparing him to study for hours at a stretch without constant supervision.

A survey conducted by the WHO reported that Indian mothers spend 7.5 hours per week on childcare and 1.3 hours on child development activities, totalling nearly nine hours. In 2021, American mothers spent 12.3 hours a week on their children.

The guilt is more acute among double-income families. And coaching centres are tapping into the fears of parents, says Dr Desai.

Balhara is willing to give up football to become a software engineer. He wants to go to the India Institute of technology (IIT) in Delhi but the road is tarred with school and two to three hours of private tuition for maths, his weak subject.

“Classes in school are not doing enough to help me reach where I aim. My mother hardly knows anything about the route to IIT-D and my father is busy man,” he says.

For the most part, students have resigned themselves to the year-round cycle of school and tuitions that culminate in exams. “Parental pressure and the tiring school and tuition classes take a toll on you,” says the class 12 student from Sanskriti School.

“In the beginning, you complain, but then you start feeling grateful. It’s the only way you can land a seat in an IIT or a medical college,” she says.

Most of the students that ThePrint spoke to view school years as crucial to their careers—that the never-ending cycle of studies will end once they get a job. But the machinery of coaching industry has already expanded its reach to include adults. Being ready to thrive in a post-manufacturing era of service sector jobs and AI-driven economy calls for constant hamster wheel-style upgrades. Upskilling and reskilling are the new buzzwords.

The coaching culture epidemic is not just about school students. Landing a job doesn’t end it. The world changes at the blink of an eye now.

By June 2022, online course provider Coursera for Business had 150 companies in India using it, compared to 98 the previous year, according to a Financial Express report. UpGrad claimed that in the first quarter of fiscal year 2023, it had “facilitated over 450 career transitions for its learners into the MBA domain.”

One platform took out a full front-page advertisement in a popular national daily promising to make India a ‘Vishwa Guru’. “Our LifeLong Learning Classroom is growing and we won’t stop until we make it 1.4 billion strong,” it vowed.

For Indians racing to catch up, life is an unending classroom where the bell just doesn’t go off.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)