New Delhi: A candlelight vigil at India Gate, with perhaps a rousing song or two, some clever slogans on colourful placards demanding clean air, clean governance, justice. For many Indians who were not yet born in 2006, or were too young to remember, this will seem like a regular occurrence in Delhi. NBD, as they say. But many of us who do remember the events of early 2006 know differently.

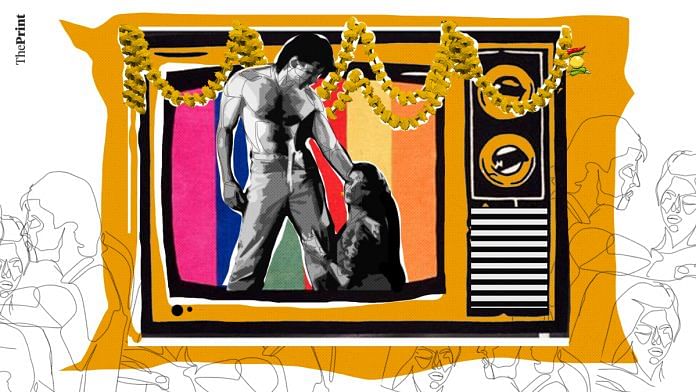

In January of that year, Rakeysh Omprakash Mehra’s movie Rang De Basanti had opened in theatres. Audiences were moved by its portrayal of a generation of young, urban Indians’ disillusionment with the system. It sparked furious debate about the right and wrong of taking the law into one’s own hands, but it was unanimously acclaimed for its depiction of urban India’s protest for a better country.

And then, mere weeks later, some of the movie’s scenes played out in real life — in February, when all the accused in the Jessica Lall murder case were acquitted and newspaper headlines screamed “No One Killed Jessica”, it shocked, perhaps for the first time in our generation, the somnolent upper classes and media into organising public protests of a type and scale not seen in India — not by many of us, at least.

There were SMS campaigns, petitions, candlelight vigils at India Gate and other parts of the country. The case went into appeal and the intense public pressure ensured that the hearings were fast-tracked. In December of that year, the Delhi High Court overturned the verdict. It seemed like a watershed in India’s fight against the system. And it was in no small part thanks to Bollywood.

Also read: Why Bollywood needs a Parvathy Thiruvothu — an actress not afraid of the F-word

Portrayal of reality versus glorification

The relationship between art and life has dominated cultural discourse for at least 2,000 years. From Aristotle’s mimesis to Oscar Wilde’s opposition to it, the question of art imitating life or vice versa is a complicated one. And nowhere is this more complicated than India, where popular culture, especially Hindi cinema, is a frequent target for glorifying certain crimes or societal problems.

Filmmakers often invoke ‘freedom of expression’ and ‘just portraying reality’ when questioned about the kind of movies they make, but the fact is that cinema, especially Bollywood, is undoubtedly India’s most effective messaging tool, so to deny its influence would be disingenuous. Recently, in a panel discussion on Film Companion, actor Parvathy Thiruvothu called out movies like the Telugu Arjun Reddy (and its Hindi remake Kabir Singh) for glorifying violence against women. She made a clear distinction between portraying a reality and glorifying it.

Deepali Desai from Breakthrough, an NGO that works to end violence and discrimination against women and girls, gives an example of how portrayal and glorification are very different. “Take the 2006 film Provoked and then Kabir Singh. In Provoked, the husband is dominant, aggressive and abusive — but his actions have not been glorified. In fact, they’ve been depicted as horrifying, enabling its identifying and calling-out. The film let its audience realise just how horrifying intimate partner violence is. [But] Kabir Singh is dominant, aggressive and abusive. He will go down in history as a ‘hero’ and his violent actions have been glorified as part of the ‘hero’s’ entitlement.”

In fact, Breakthrough has been in the news lately for its ongoing petition to make it mandatory for scenes depicting and referencing all forms of violence against women and girls to carry disclaimers and messages of condemnation on screen — both in cinema and on television.

The petition, addressed to the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC) and the Information & Broadcasting Ministry, has garnered over 1,00,000 signatures. It demands that “a disclaimer is displayed prominently at the bottom of the screen saying these acts of violence are strictly punishable as per our laws. Films that depict such violence also include a disclaimer. A 30-second public service ad condemning all forms of violence is broadcast before the film or during the interval”.

Desai adds that keeping in mind the social and cultural capital filmmakers have, it is necessary to “make a dent in the narrative on blatant on-screen misogyny. To scratch the surface, acts of and references (like jokes) to violence against women and girls must be identified for what they are”. She explains that a directive has already been issued by the Kerala State Human Rights Commission to the CBFC and the cultural affairs department. Breakthrough is hoping to submit its petition in a matter of days.

Also read: One year after India’s big #MeToo wave, a reality check

Effective or merely palliative?

But will these disclaimers/messages just be ignored like the smoking and alcohol disclaimers during a movie and anti-smoking ads before it? Stuti Ramachandra, a freelance executive producer who has worked on Fukrey Returns and Gully Boy and is currently working on Toofan, isn’t hopeful. “People are so mesmerised by what they see, they’re not reading the fine print.” She also believes that it has to do with the quality of the messaging. “I often hear people laugh during the no-smoking ad (the one where the man smokes near his kid) and that’s the exact opposite of prevention. The quality is subpar, the tone is condescending and I do feel we have to do better.”

To the question of whether the annoyance of being made to add a disclaimer will force filmmakers to not have problematic scenes or songs, she says, “Unfortunately, not at all. They will just add it and then move on. Better still I worry it’ll work as a licence to push the envelope of crap further.”

Scherezade Sanchita Siobhan, a psychologist, author and community catalyst, believes these warnings can sometimes produce the opposite effect to what is intended, or a defensive reaction (similar to #notallmen).

“A lot of people don’t think of rape or assault as a social problem emerging from systemically oppressive structures but more of an individual problem. Research proves that very drastic warning labels on smoking packets, for example, lead to cognitive dissonance and a more defensive set of responses,” she says. “In some cases, when cigarette packets carry very graphic imagery, smokers instantly disengage and don’t pay heed. The more a warning label focuses on an individualistic approach of blaming and shaming, the less its impact on a larger group. Socially relatable and mindful engagement has a better chance of being remembered as well as more positive outcome.”

Desai is clear, though, that Breakthrough is not asking for a pop-up on every such scene (and in a movie like Kabir Singh, it would need to be present almost throughout), but a message before the movie and/or in the interval. She points out that, currently, gender violence is being normalised with no counter-narrative in popular culture, under the guise of freedom of expression and portrayal of reality. “It is not the presence of violence, but the justification of scenes of violence against women as well as the valorisation of the abusers in such scenes that must be called out.”

It is interesting to recall that in Tasmania, a few years ago, a man of Indian origin was let off with a restraining order in two cases of stalking. The magistrate appreciated his defence that his cultural background (Bollywood movies) gave him the message that stalking was an act that would be rewarded. Given this kind of impact, what is the responsibility of a filmmaker and how does that sit with their freedom of expression?

Ramachandra admits that, as a filmmaker, it’s tempting to opt for unfettered freedom, but “how I feel as a citizen, and human being, is stronger”. “India is such a unique country in terms of how we idol worship our stars — they are literally god. When these so-called stars then play roles that are detrimental to society, they have to accept that they have played a role in our behaviour and mentality.”

She adds, “We can’t afford absolute freedom of expression in a country that is as uneducated as ours is, so much below the poverty line in its majority, and cinema has to guide the way. There can be freedom of expression, but it has to be responsible.”

Also read: #MeToo movement shook Bollywood status quo, hasn’t fizzled out yet: Tisca Chopra

Who decides what is violent?

A major question then becomes — who gets to decide what constitutes violence, says Aparna Jain, author and leadership coach, who conducts diversity and leadership workshops at workplaces.

Neither our moviemakers nor the CBFC, which is also called the censor board even though its role is to certify, are nuanced or mature enough to understand the different kinds of violence that exist, especially in terms of gender, she explains.

“What about gaslighting and emotional abuse? What about marital rape, which is not even a crime in India? Rape jokes, locker-room talk — doesn’t all of it add up to a culture of violence against women?”

Ramachandra agrees. “Our censor board won’t allow us to show nudity in an artistic way, or voice abuse where it is warranted by the scenario, but it allows jokes and behaviour that are misogynistic and crass,” she says, ruefully.

“We are far away from emotional abuse being qualified. Let’s start with marital rape not being glorified, ‘eve-teasing’ not being shown as a tool to woo a woman and harassment not being shown as humorous,” Ramachandra adds.

As for how the Breakthrough petition will deal with something like marital rape, Desai states they do not see violence only in terms of existing laws, but universal frameworks of human rights.

“This includes existing misogynistic behaviours and norms that might not have legality involved,b have been identified or experienced as violence by women in their everyday lives. The purpose of this petition is to call out the glorification of such misogynistic behaviours and practices in our films — this includes sexist jokes and rape jokes as well.”

She adds that Lipstick Under My Burkha (which the CBFC had huge issues with) “depicted the scene in question as unacceptable towards a woman. So even though the present laws do not recognise it, it doesn’t prevent filmmakers from depicting it for what it is”.

Siobhan, who suggests having a team of specialists, social workers and mental health professionals vet cinematic content for these messages, reiterates that “physical abuse or rape doesn’t exist in a vacuum”. “All rape is accompanied by emotional violence whether explicit or implicit. In fact, emotional violence is the origin for most other expressions of violence.”

Less warning, more sensitisation

Reacting to director Daniel Shravan’s recent comments on how women should welcome rape in order to avoid being murdered, Jain questions whether a warning would have any impact on a filmmaker with that kind of mindset.

She believes that more than a cursory warning or disclaimer, a strong message of condemnation from filmmakers during their press conferences, plus statistics on violence against women shown at the beginning or end of a film, might be more impactful.

Desai, while agreeing in principle, argues that “many are even unable to identify acts of gendered violence. The disclaimer in the middle is then handy in films where violence has been packaged as romance, comedy or as a self-righteous path for the ‘hero’ to walk down.”

Jain also suggests that regular sensitisation workshops with people in the film industry would have more of an impact than a disclaimer, the key word being regular.

“We tend to see rape as a one-time, isolated problem, not a systemic one, and that is part of the problem. We distance ourselves from a problem and say those perpetrators are other people,” she adds.

Siobhan, taking the conversation back to movie disclaimers, feels they “have a psychologically palliative effect when we feel like only a select group of people can harm or be harmed. We only feel alarmed when a deplorable and ghastly act is committed and then publicised. We don’t focus on daily microaggressions against women and particularly women from minority backgrounds.”

These disclaimers, says Desai, are meant to bring people’s attention to the problem. But ultimately, it boils down to the intent of the filmmaker.

Also read: Picture abhi patriarchy hai: Studying Bollywood’s sexism disease

Well written. The author presents several facets of a complicated issue.

Something to consider wrt to freedom of expression. There are responsibilities associated with freedoms, though not enforceable necessarily, too.

Content creators, however, aren’t

engaged in expression per se. They are engaged in a commercial activity. In a sense, they sell sex, drugs and violence, as the say. In fact, intentionally or intuitively, they do so in such a way that their product resonantes with consumers as measured by the success of the content. Commercial activities can and should be regulated, keeping a sense of public good in mind.

To suggest that portrayal of fictional violence is freedom of expression and hence shouldn’t be regulated belays the fact that violent content is an effective recruitment tool for those who want to perpetrate violence on others.

The argument of course will be made highlighting the intent behind the creation, but research into the pre-frontal cortex and the functioning of mirror neurons points to our inability, at times, to tell the difference between reality and fiction. To add to the complexity, emotion and emotional states modify perception in different ways, at times crystalizing memory, at other times, modifying it. Normalizing violent behavior starts from Tom and Jerry at home, perpetuates itself amid a cocktail of hormones at school, and the fantasy can play out as repressed adults.

How many of us develop the self awareness to break out from this cycle?

Content creators should be aware of a simple fact. Their content is a part of the milieu where they both perpetuate and reflect behaviors of society. They are not separate from it.