It’s 2030. Ajay lives in India. In his teens he experienced an episode of depression, so, as a new undergraduate, he was keen to sign up for a mental healthcare service when offered. Ajay chose a service that used mobile phone and internet technologies to enable him to carefully manage his personal information.

He would later develop clinical depression but spotted that something wasn’t right early on when the feedback from his mental healthcare app highlighted changes in his sociability. (He was sending fewer messages and leaving his room only to go to campus.) Shortly thereafter, he received a message on his phone inviting him to get in touch with a mental health therapist; the message also offered a choice of channels through which he could get in touch.

Now in his mid-20s, Ajay’s depression is well under control. He has learned to recognize when he’s too anxious and beginning to feel low, can practise the techniques he has learned using online tools and has easy access to high-quality advice. His progress through the rare depressive episodes he still experiences is carefully tracked. If he does not respond to the initial, self-care treatment prescribed, he can be quickly referred to a medical professional. Ajay’s experience is replicated across the world in low, middle and high-income countries as similar technology-supported mental illness prevention, prediction and treatment services are available to all.

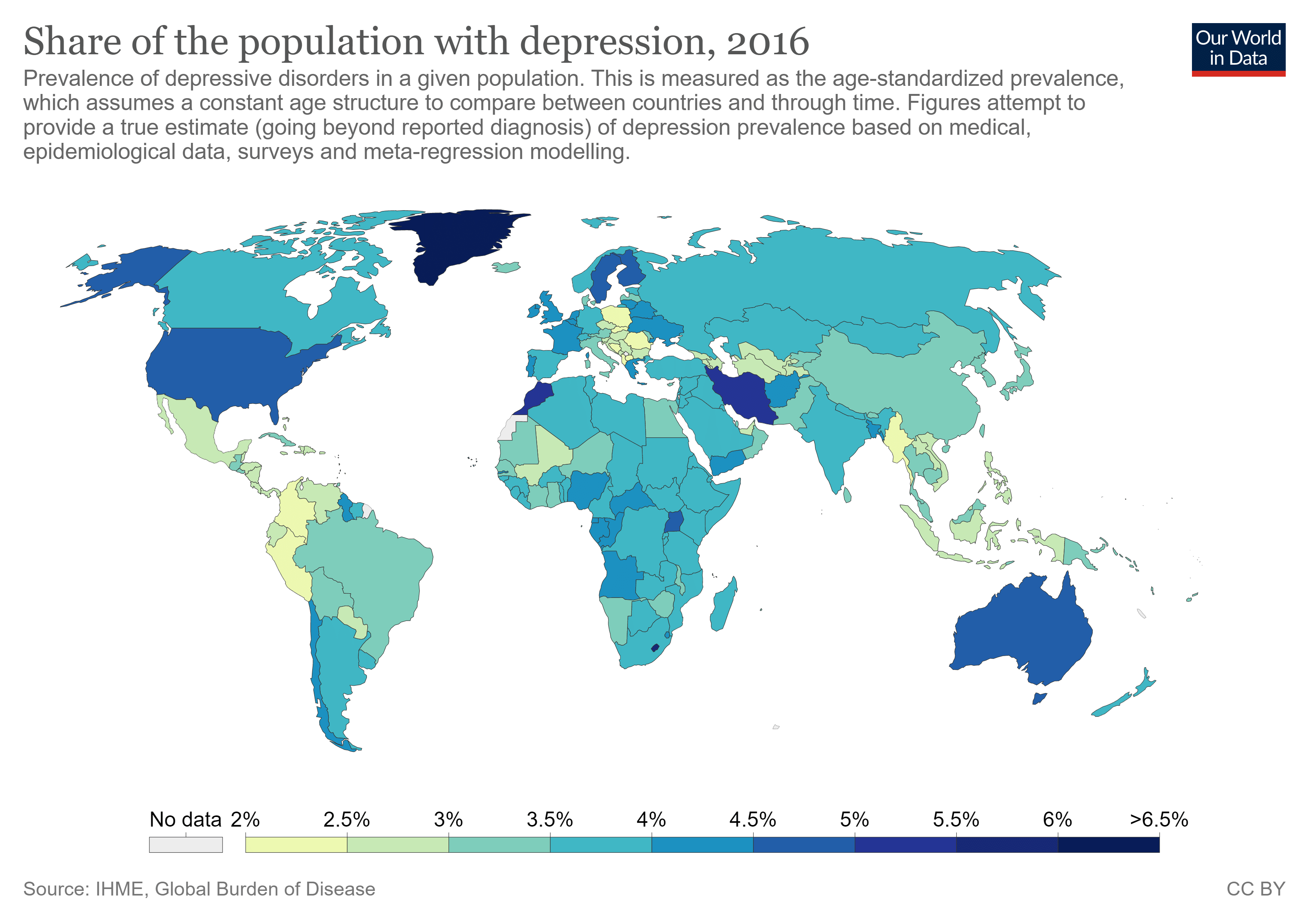

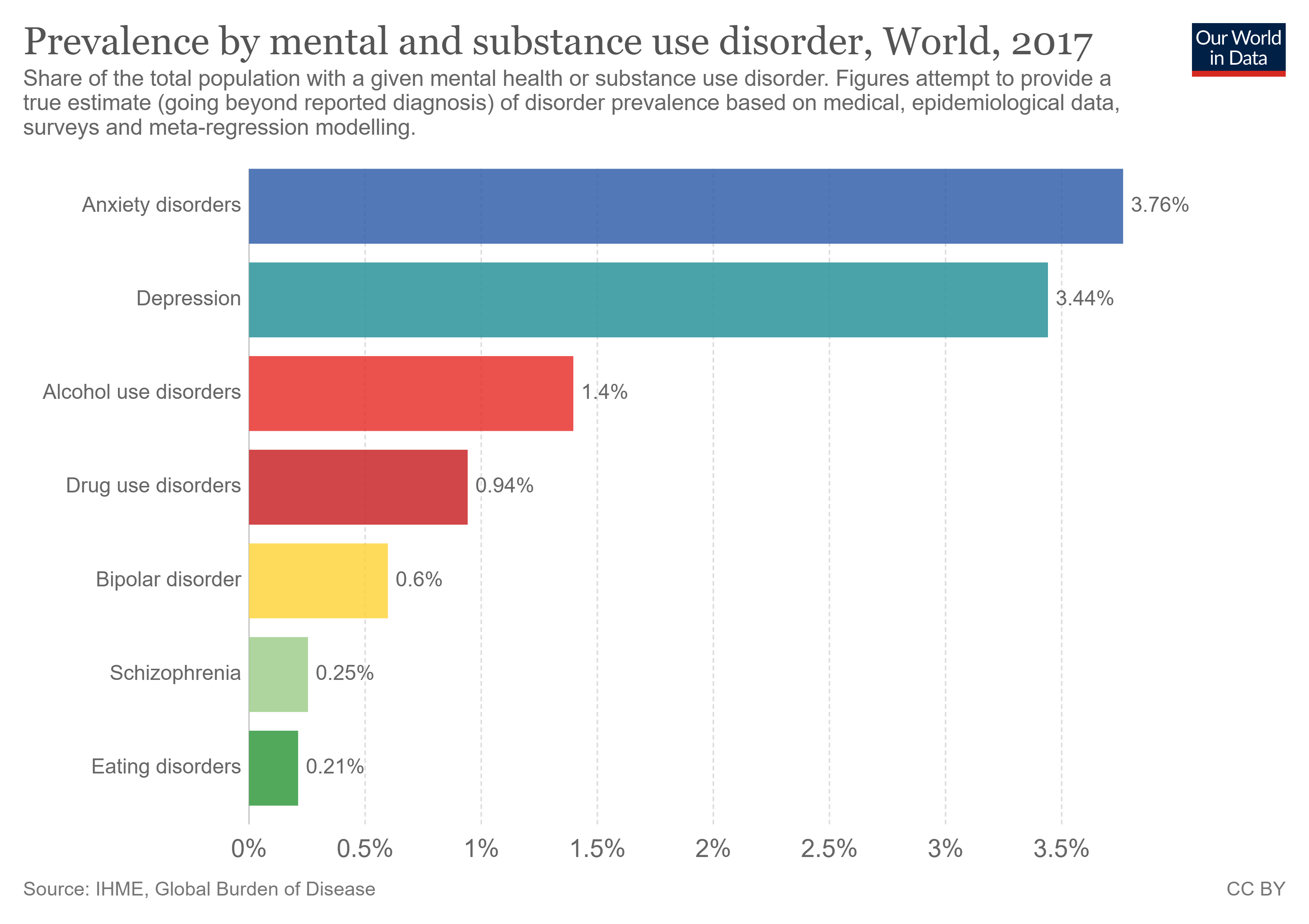

Now back to the present reality, which could not be more different. Mental health disorders are among the leading causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide and could cost the global economy some $16 trillion by 2030. Today, an estimated 300 million people worldwide suffer from depression, while suicide is the second leading cause of death among young people.

Most mental illnesses are treatable. Everyone has the right to good mental health and yet, worldwide, some estimates suggest that around two-thirds of people experiencing a mental health challenge go unsupported. One UK study of more than 500 adults found that a quarter of individuals with mental health issues waited more than three months to see an NHS mental health specialist; 6% had waited at least a year. In the poorest areas, isolation, financial hardship and an inability to find even limited treatment are commonplace.

However, an experience such as Ajay’s is not as much of a pipe dream as it might first appear. The rapid spread of smartphone apps, sensors, chatbots, social media, digital voice assistants and virtual avatars, along with cloud-based, deep-learning artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) tools offers new opportunities to scale access to mental healthcare. Tech start-ups in the mental health space have seen funding treble in the past five years, reaching a record $602 million in 2018. In short, technology is already being used widely in mental healthcare. It’s something consumers are open to: 65% of workers in a UK study (and 75% of the youngest workers) were positive about the role of technology in managing their mental health.

It is clear that technology already has much to offer in terms of providing and improving access to better mental healthcare. It is, therefore, reasonable to ask why more has not already been done to take advantage of these tools. Traditional challenges to adoption, such as a lack of funding, play a part, but there is also an understanding within the industry that greater use of new and existing technologies in this space requires policy-makers and practitioners to navigate a complex web of ethical dilemmas, particularly in areas such as data privacy and individuals’ rights. The general nervousness surrounding this journey is understandable, but it has resulted in a reluctance to develop and scale technology-based initiatives that could improve – and save – large numbers of lives.

Given these findings, it is essential for governments, policy-makers, business leaders and practitioners to step up and address the barriers keeping effective treatments from those who need them. Primarily, these barriers are ethical considerations and a lack of better, evidence-based research. Many mental health-focused apps do not report evidence from peer-reviewed controlled clinical trials to support their effectiveness and even for those that do, rapid advances in technology may render the research outdated. Furthermore, the absence of a consensual, globally harmonious, ethical and big-data framework has led to companies adopting their own consent, transparency, privacy and data policies.

The Global Future Council on Technology for Mental Health will examine the strengths and limitations of emerging technologies, especially AI and ML, for mental healthcare applications. It will highlight the work needed to scale the adoption of technology, in a fair and evidence-based manner, to ensure that everyone, everywhere, who is facing mental ill-health, can get the help they seek.

Also read: 36% patients in mental health facilities stay over a year — way above ‘6-week requirement’