In the sea of blue that takes over Dadar streets—right in the middle of looming high-rises, branded stores, Shiv Sena Bhawan, and countless symbols of ‘upper caste’ modernity—the microcosm of Dalit life is unmistakable. It represents the community’s love for BR Ambedkar and what he means to his followers, half a million of whom assemble every year in Mumbai on Mahaparinirvan Din, Babasaheb’s death anniversary. In filmmaker Somnath Waghmare’s hour-long documentary Chaityabhumi, the “eminent Indian philosopher, jurist, politician, social reformer” emerges as an imposing figure in every smile, handshake, prayer, song, and chant of “Jai Bhim”.

Ambedkar is everywhere in Chaityabhumi; so is Waghmare’s idea behind making the film: to show Dalit assertion and their fight for equality. In the process, Waghmare creates an unavoidable ‘public memory’ of Dalits singing, chanting, reading, and openly resisting.

For upper castes, though, such ‘public memories’ have been created with the help of State or public money, which has established public spaces that are exclusive to them, according to Rahul Sonpimple, scholar and president of the All India Independent Scheduled Caste Association. But when it comes to Ambedkar or the marginalised sections, most of the public memories have been created by the communities.

“Ambedkarities are a threat for them now because they are creating the public memories about Ambedkar.”

“Ambedkar became part of the so-called mainstream not because the government wanted it, not because some liberal academician or university people wanted it, but because of his people, his followers who struggled even to have a small statue of Ambedkar in the village.”

That is why, Sonpimple explains, the upper castes have moved from criticising Ambedkar to criticising Ambedkarites.

“Ambedkarities are a threat for them now because they are creating the public memories about Ambedkar.”

Also read: Brahmin, anti-caste, caring for cows — a writer walks on eggshells of Hindutva & Ambedkar

A living tribute to Babasaheb

Waghmare’s Chaityabhumi makes several statements over its one-hour runtime. The documentary on Babasaheb’s final resting place at Dadar in Mumbai serves as a walking tour for Indians who are oblivious to the drumbeats of Dalit assertion that plays out in their midst every 6 December.

On this day in 1956, Ambedkar left behind a legacy that his millions of followers are keeping alive not just by congregating at his memorial every year but also in their everyday resistance to caste oppression.

Chaityabhumi opens with black-and-white close-up shots of the only tangible memories of Ambedkar that survive today. As the camera pans through his room, desk, bed, and the pictures hung on the wall, the silence is suddenly broken by one of his speeches where he is explaining the real “difficulty” faced by the Dalit community. It’s not about the ultimate future, Ambedkar’s voiceover declares. “Our difficulty is how to make the heterogeneous mass that we have today take a decision in common and march in a cooperative way on that road which is bound to lead us to unity. Our difficulty is not with regard to the ultimate. Our difficulty is with regard to the beginning.”

Seemingly, this remark serves as a cue for Waghmare to tell upper-caste Hindus why their stories about Dalit lives must move away from “atrocities or manual scavenging”. In that sense, Chaityabhumi marks a new beginning in how to tell Dalit stories on screen.

Among the major highlights of Chaityabhumi are its interviews. Besides the one with Sonpimple, Waghmare speaks to Pranjali Kureel, a Commonwealth scholar, who highlights the contrast between upper-caste Hindu symbols and Ambedkarite symbols. The former represents domination or affirms oppression; the latter represents nothing but justice, freedom, freedom of mind, and equality.

Also read: Untouchability to social jealousy—Understanding 21st century Dalit in the emerging scholarship

It’s cultural as much as political

What Sonpimple and Kureel describe in words, Waghmare uses the site and the people to put those thoughts in images. There is always some act, some performance going on at Chaityabhumi, and Waghmare is present with his camera to capture the celebration, the solidarity, the resistance, and an ‘awakened’ mass. And just like Kanshi Ram Jayanti is “a reminder of the shared cultural-political history of being part of the Bahujan movement”, as noted by scholar K Kalyani, Ambedkar’s Chaityabhumi is also a place where Dalit politics turns to cultural expressions to register both the idea of resistance and emancipation.

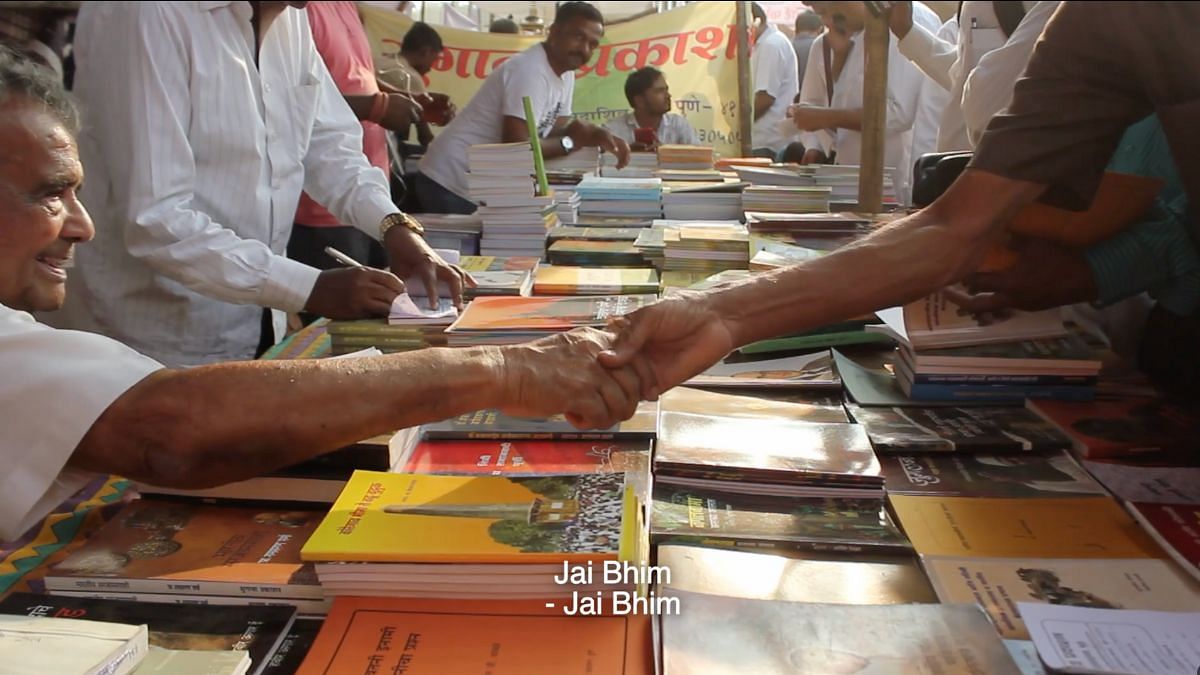

These cultural expressions are visible at the bookstalls, in the Dhamma prayers playing continuously on loudspeakers, in the songs of Rahul Telgote, Charan Jadhav, Ambika Kamble, and also in the act of lok shahir (people’s poet) Dhammarakshit Randive and his team.

If the 63rd Mahaparinirvan Din is the first introduction to Chaityabhumi for a non-Dalit, then it explains why the cultural—and also political—assembly of half a million people from all over the country every year at Dadar continues to escape them. This stems not from unfamiliarity but from a resigned indifference to the public display of Ambedkarism and Buddhism. As Jai Bhim Kalamanch’s Kamble sings on the mic, “In this country, true rulership belongs to Bhimrao.” How would that sit with the mala fide rulers?

So, what does Chaityabhumi mean for the people who visit the memorial?

For Kureel, visiting Chaityabhumi brings the realisation that “the fire is still burning”.

“Even though academia and the media have erased or manipulated or even appropriated the ideas of Babasaheb, when you go to Chaityabhumi, you realise his legacy is still being taken forward.”

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)