In his book Between Two Tanpuras, music critic Vamanrao H. Deshpande wrote that veteran musician Govindrao Tembe once called Kumar Gandharva a “question mark” in the field of music. Others preferred to refer to him as an “exclamation mark”.

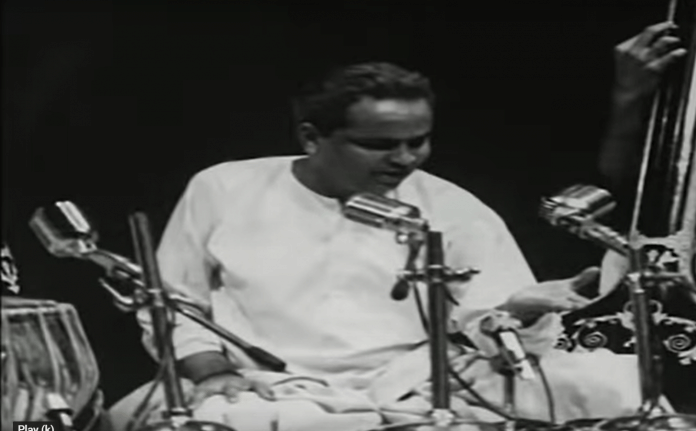

One of the most famous and revered Hindustani classical singers in India, Kumar Gandharva was lauded as a musical prodigy from the time he was a young boy, and his music can still be found on new-age streaming platforms like Spotify, Apple Music, Soundcloud and Saavn, almost 28 years after he passed away in 1992.

But the enviable legacy he has carved for himself was not just because of his skill as a musician. It is also because of his courage. He dared to create new ragas, new compositions, and an entirely new tradition. Breaking the traditional method of singing within the confines of a particular gharana, he deviated from the age-old norm to create his very own style, which earned him a reputation of being both a rebel and a pioneer.

In his book, Deshpande notes that a singer usually rearranges musical phrases he has heard from his teacher and other musicians, rebuilding from countless “bricks” accumulated over time, like raw material handed down from one generation to the next. But Kumar, explains Deshpande, created his “own bricks according to his own genius”, using them freely in terms of what he wanted to construct and how he wanted to express it, creating combinations of notes that had never been conceived before.

“There was no room here for adulteration — the product is oven fresh”, he said of the maverick musician’s independent, original creations.

Also read: Kelucharan Mohapatra, a perfectionist and guru par excellence who redefined Odissi dance

Child prodigy to tuberculosis patient

Kumar was born Shivputra Komkali on 8 April 1924 in Belgaum, Karnataka, to a family where music was an integral part of the household. His older brother was an avid singer, and his father was a huge fan of renowned Marathi singer and actor Bal Gandharva. Young Shivputra would sit around and absorb his musical surroundings, but it was only at the age of eight when he actually sang for the first time, leaving his family members shocked.

It was the head of his father’s family who, upon hearing him sing, pronounced that he was like Gandharva, the mythological word for celestial musical spirits, and from then on, he was Kumar Gandharva. As his childhood friend and peer Chandrashekhar Rele recalls in Jabbar Patel’s documentary Hans Akela, the perfect sur that was in Bal Gandharva’s music was innate to the prodigy.

He was enrolled at the Deodhar School of Music in Mumbai. Established by renowned musicologist B.R. Deodhar, the school was known for breaking from the gharana tradition and appreciating several different schools of music. It was here that his genius was noticed by his guru and peers alike, and even before he graduated, he began teaching other students. By his early 20s, he had successfully completed his musical education and was well on his way to starting a long and successful career.

But then tragedy struck when he contracted tuberculosis, and was told by doctors that singing could be fatal for him. It was during this time that he moved from his home town in Belgaum to Dewas in the Malwa region of Madhya Pradesh. It seemed like things were doomed until finally in 1952 the antibiotic Streptomycin, which had emerged as a cure for tuberculosis, was introduced in India.

The musician slowly recovered, but, was unable to sing in the same way he had before due to a compromised lung. He made changes to his style of singing and returned to the music world with renewed zest and rawness. He began to compose a number of khayals and bandishes, and also became deeply vested in spotlighting the folk music of the region.

Also read: Pandit Ravi Shankar — the sitar maestro who introduced ragas to the West

A life in Dewas

Not only did Kumar experiment with ragas, he also started to experiment with different music genres like bhajans and folk songs. It was also during his time in the sleepy town of Dewas that he became interested in the teachings and music of Kabir, a fact that was initially criticised by many.

In scholar Shabhnam Virmani’s film that explores Kumar Gandharva’s tryst with Kabir’s music, his longtime friend Ram Kolhatkar recalls how many would ask why Gandharva was singing a beggar’s song. “Even renowned critics spoke like that. But still, Kumarji continued singing Kabir. He understood Kabir for himself, and then inspired others to listen and understand him. ‘Listen to what Kabir is saying,’ he would say.”

Kalapini Komkali, Kumar’s daughter and a noted classical singer herself, recalled how he used to say “‘Main Malwe ka aur Malwa mera’ (I am Malwa’s and Malwa is mine).” It was Dewas, his “karmbhoomi” (place of work), that nursed him back to health, its dry climate providing respite to his tuberculosis, and the sight of farmers resting under bakula trees giving him inspiration.

Shubha Mudgal, one of his students, also noted that many of his song texts revealed the “undeniable influence” of the Malwi dialect, which was understandable as he spent nearly 44 out of the 68 years of his life in Dewas. As Virmani’s film shows, Kumar’s music is still very much in the soul of Dewas, which turned his home into a museum and a tangible monument to his legacy.

Also read: Ustad Alla Rakha, whom the world hailed as ‘Einstein’ & ‘Picasso’ of the tabla