New Delhi: Fifty years on, there is a glut of Emergency literature in the market. But the new book, The Conscience Network: A Chronicle of Resistance to a Dictatorship by Sugata Srinivasaraju, is really looking at an understudied subject.

It focuses on the activities of Indians living in America – and how they organised and mobilised and resisted Indira Gandhi’s “dictatorial rule between 1975 and 1977”.

Read edited excerpts from the conversation with Srinivasaraju. For the full interview, do visit ThePrint’s YouTube channel.

RL: Why is it that this hasn’t been studied before?

SS: Most of the literature that has come out of the Emergency is memoirs – people speaking about their terms in jail, people speaking about the torture that they underwent. And then, there is also creative literature. But those focus on what happened in India. And they look at Indira Gandhi.

But this book is different. We speak so much about the international pressure on Indira Gandhi to lift the Emergency or hold the elections. But nobody actually examined that international pressure. Who was putting pressure on her? What kind of debate was taking place in the West? Obviously, nobody in India could have accessed or read that because everything was banned and nothing was being allowed to enter the country. Nobody had examined the Western newspapers or Western media, especially America’s.

RL: The book definitely moves the needle on Emergency literature. It begins with these people who leave India in the ’60s—exploring their family background, their education, and what drives them to leave India and go to the United States. What American dream were they chasing, and what kind of India were they leaving behind? And why is it that, once they arrive in the US, instead of chasing the American dream, they start fixing the India story?

SS: That’s fascinating. The way you put it is really, really, really fascinating. So yes, they left India, which was in a crisis. You know, there was a food crisis, and there was a political crisis because in 1964, Nehru was gone. Then, there were two prime ministers after that. And Indira Gandhi was just about settling in. The five-year plans had not delivered anything. And here were a bunch of youngsters who were academically extremely bright. At least most of them were from an IIT, the elite institution Nehru had built, and turned their back on India.

It was the usual thing about chasing money, chasing professional success, chasing a certain kind of satisfaction professionally. So, they look at the West, and America is also changing, allowing immigrants to come in. It opens up for Asians, allowing American institutions to exploit the talent of the world. And in India, interestingly, at that point, we are discussing brain drain. Bhagwati, the economist, is speaking of a brain drain tax. That should explain the situation in India at that point in time – hunger, brain drain, economic collapse, and political uncertainty.

RL: And while this is happening in India, the ’60s in America were a heady time of social movements. The civil rights movement, the feminist movement, the environmental movement, and the disability rights movement. An expansion of the idea of freedom was also going on. That’s the America they land in?

SS: The walk on Washington happened in 1962, led by Martin Luther King. So, although we are speaking of America as a land of opportunity, the blacks within America themselves are facing segregation at the time. The American Dream is a marketing line. And there are these people who are fighting for their rights, their voting rights, against their segregation, and are demanding to be treated equally. And there is the environmental awareness that is spreading. You have Ralph Nader doing the consumer movement. People have started resisting the Vietnam War, too.

All this impacts these Indians. And then they are also watching Richard Nixon go down in the early ’70s with Watergate.

RL: And you call the ’70s decade the decade of ill-repute in both America and India?

SS: Absolutely. So, ill-repute in India is because of the Emergency, and there (in the US) it is because of Nixon. This decade emboldened the American press and the public to demand accountability from their democracies. The ’70s taught them to do a lot of things.

RL: And tell me a little bit about how they began organising and mobilising. Was it a response to what Jai Prakash Narayan was doing here?

SS: The origins were interesting because they had already, in the early ’70s, built a development network in America. It’s not just about going and doing something in the villages, but it’s about fusing technology for the advancement of India and the advancement of rural India. They kept rural India at the centre of their piece.

And then, they started looking at technology that they were accessing in America, and ‘how do we improve lives?’ For example, Amulya Reddy, who was here at the Indian Institute of Science, was looking at a chula (cooking stove), and how to make life simple for an Indian woman. These people were collaborating on a lot of such things. And the very interesting thing is that their Indian dream was not a political dream; it was not a dream that surrounded power, ambitions, or whatever. It was about development. So that was very, very unique. And they also embraced certain Gandhian ideals.

RL: So, the fight for a development movement somewhere morphed into democracy?

SS: Right. That is because they thought that if you have to bring about development, there has to be a kind of flat terrain, which allows everybody the same opportunity. And that could be provided only by democracy and not by a dictatorship.

RL: Tell me about the first anti-Emergency protest outside the Indian embassy in Washington. You say about 75 to 80 people turned up?

SS: That was not a well-organised protest. It was a first attempt at organising against the Emergency. These people were trying to be very cautious, defining themselves very clearly. Who are we? What do we believe in? And then putting this development dream for India forward.

They were saying that we are saving democracy, not because we are opposed to Indira Gandhi, and not because we have embraced the JP movement. It’s because we cannot allow India to lose its opportunity.

RL: So, it was not partisan politics?

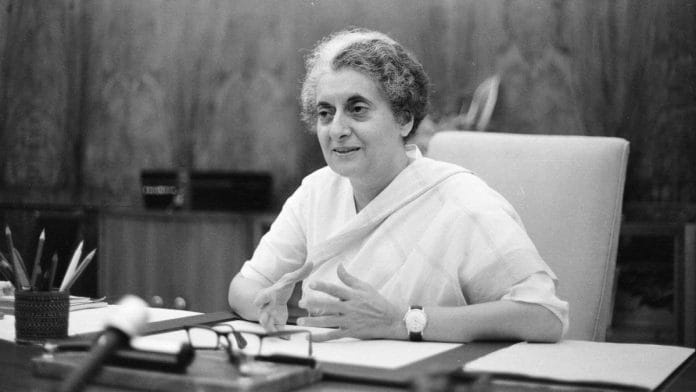

SS: It was not partisan politics at all. In fact, the exemplary thing that I noticed in all their literature and their letter correspondence is that Indira Gandhi was never made a personal target. It is the issue that democracy becomes central. Please do not see my book as an anti-Indira Gandhi book. It is a more pro-democracy book.

RL: How do they organise? They go to campuses, they address diaspora meets, and they raise funds. Can you tell us about the nuts and bolts of how they did it?

SS: First, they start by sending out Professor Anand Kumar, who was, at that point, doing his PhD in sociology at the University of Chicago. He came from JNU (Jawaharlal Nehru University) – a student leader and president of JNU who had defeated Prakash Karat in the elections. He was already in the JP movement because he had come under the influence of JP, and he was in close touch with JP, and suddenly he gets this scholarship to go and do his PhD.

It’s an Indian government scholarship, and he lands in America in January 1975. He is the one who begins talking about what’s happening in India very seriously, in political language.

Ravi Chopra and SR Hiremath, and Sri Kumar Poddar are very, very central to this story. Sri Kumar Poddar, who was the initial financier of the whole thing and already well settled in America, was the first of the bunch who went in the late ’50s.

He is a tsar in America, has already made his money, and is related to Ramnath Goenka. Poddar is also politically aware and has a huge network in America already because he is raising money for all these presidential candidates, like Eugene McCarthy. So, he joins these people, and they send Anand Kumar on a lecture tour across America. The first lecture tour happens even before the Emergency is declared. So they are smelling something, and want to create awareness about the democratic crisis in India. Anand Kumar goes to several American cities and campuses, talking about what is happening in India.

Their first organised protest is in front of the embassy or the residence of the ambassador, and they time it around August 15. That becomes a huge success because that attracts the attention of the American media. And they get a celebrity columnist called Mary McGrory to write about them. That’s the first big exposure they get. That’s also the first big alarm that is raised inside the embassy.

RL: And what kind of coalitions are they building with Americans? And who are these?

SS: There was a lot of pressure from the Left because the Left was more prominent—the extreme left, what you would call CPI-ML (Communist Party of India-Marxist Leninist). They were trying to build their own thing because they saw an opportunity to ‘build a revolution’ in India and not to restore democracy. And then there was also the Communist Party of Canada. Then there was the Ghadar party, which goes back to the freedom movement and was also extreme Left. There were a lot of disagreements between them. One would beat up the other. But these people don’t succumb to the pressure that the Left puts. The Right is still pussyfooting.

RL: In fact, you say that there was not much of a Right movement in America at the time.

SS: Yeah, VHP (Vishwa Hindu Parishad) had just started in ’71. Mahesh Mehta is the founder of VHP in America. Then there’s also Ram Gehani or Jitendra Kumar, who have a strong RSS background but are, in fact, trying to be part of this democratic process that these people are trying to build. They say that we will not decide anything on the basis of ideology but on the unity of action. We are not going to allow a kind of violent Leftist thing or a Rightist campaign.

RL: Let’s talk about the price they had to pay. You talk about the long, distant impact of a ruthless government on these diaspora Indians.

SS: Initially, nobody is bothered. No one. And then it becomes very serious at the end of ’75 and the beginning of ’76. The reason is that Indira Gandhi postpones the elections. Until then, America is not really worried about the Emergency. There is a lot of understanding and sympathy for Indira Gandhi in the initial months. But once she postpones the elections, America turns; they realise that she’s up to something else. So that is when the IFD (Indians for Democracy) starts getting all the attention, because they’re Centrists.

So, the consequence is that Anand Kumar loses his scholarship, something that’s very crucial for him to survive there. But the Chicago University stands up and waives his tuition fee. Then he gets a job with the Chicago Tribune as a mailman. But that is not sufficient to live in America. He also becomes a guard at the library at the University of Chicago. Jethmalani and Tarkunde, who were central figures with the JP movement in India, tell him: ‘Don’t come back, you will just become another number in jail. You stay there, stay put somehow‘. And that is why he hangs on, and his American professors help him. His fellow students start a committee in defence of Anand Kumar. His sister has been arrested; his brother-in-law has been arrested. The entire family is in a crisis.

And then, a little later, passports of all the IFD founders are impounded, except that of Ravi Chopra. Sri Kumar Poddar, Ram Gehani, and SR Hiremath – all these passports are impounded.

RL: I want to now segue into talking about some fascinating characters, like India’s then-ambassador to the United States, TN Kaul, who put up a valiant defence of Indira Gandhi and the Emergency.

SS: Kaul is a (Gandhi) family insider. He is the main propaganda machine there, going to university after university, trying to tell Americans: Why are you holding us responsible? We are doing this because JP has provoked the military to rebel against Indira Gandhi. And that’s going to create a lot of disorder. JP had not said that.

When YB Chavan comes to America, he’s booed. He meets Gerald Ford, and Henry Kissinger is in that meeting, ‘President, you shouldn’t be allowing these street protests against Indira Gandhi’. He replies, saying: We judge democracy by our standards, not Indira Gandhi’s standards.

RL: In fact, you say that because of IFD’s impact, Kaul started addressing and meeting with the diaspora community and engaging much more.

SS: That’s right. He holds these secret meetings in New York and other cities in America, trying to convince people not to be on the side of these people. There are all these cheap tricks of nationalism and national pride that are pulled out. He also says that these people are “washing dirty linen in public”.

RL: Once the Emergency is lifted, JP goes to America and gets a call from Jimmy Carter.

SS: Yeah, JP goes to America because he has a health issue and has to get a procedure done in Seattle. The dialyser that JP needed to survive, Indira Gandhi had tried to contribute money to that fund. IFD in America had said to return it – we will raise money for you. Please do not accept it for money.

JP gets a call, and it’s from Jimmy Carter. And Jimmy Carter says, ‘How are you and all that?’ And JP is confused, essentially. ‘I didn’t know that I was so important. I didn’t know that Carter knew I existed. ’

RL: What do you want the diaspora Indians in 2025 to take away from this book?

SS: This book provides a small conscience mirror, I would say. So, if they look into that, they will probably know that something more meaningful and deeper existed in our communities.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)