New Delhi: Cobwebbed, colonial laws cast long shadows in India, stifling lives, livelihoods, and language well into the 21st century. As he took centrestage in a room full of lawyers, policy wonks, and law students, Padma Shri awardee and linguist Ganesh Devy cut straight through the jargon to expose how British-era laws shape the way we think, speak, and act in modern India.

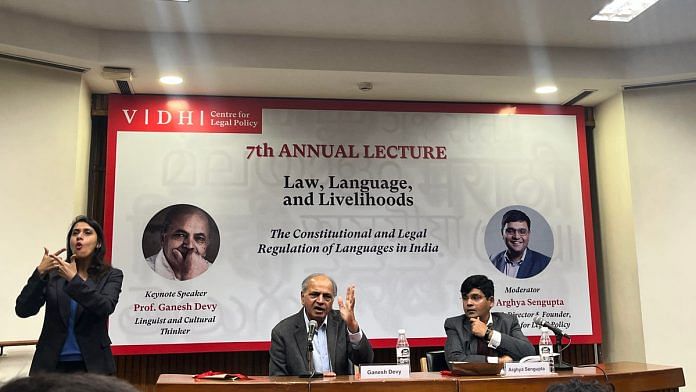

“Law is not my subject but Indian society is. And, therefore, I have decided to speak about some laws and regulations which had an impact on our society — both culturally and in terms of livelihood,” said the 73-year-old social activist, setting the tone for the seventh annual lecture of Vidhi Centre of Legal Policy.

The lecture room at Delhi’s India International Centre Annexe was brimming to its capacity of about 50, with some attendees leaning in from the doorways to catch Devy, a Sahitya Akademi Award winner, speak. The topic was a mouthful— ‘Law, Language, and Livelihoods: The Constitutional and Legal Regulation of Language in India’— but Devy’s hour-long talk was an accessible primer on the long life of legally sanctioned injustices.

To illustrate his point, Devy focused his talk on the de-notified tribes (DNTs) that exist on the fringes of 21st century India, with many living on the streets. Even today, the term DNT is largely a euphemism for the entire communities that were declared as ‘criminal’ by the British government. Scheduled Tribes, too, he noted, were a colonial-era creation.

“Does anybody in India know at all how tribes came up in India? Do any of our Vedas, Upanishads, Shashtras, Puranas explain how so many of us are castes and why others are tribes?” he asked.

Also Read: Delhi durbars flaunted the might of British Crown. They also stoked flames of resistance

‘Look at those children selling balloons…’

A sinister chapter from the colonial playbook, the Criminal Tribes Act (CTA) of 1871 branded entire communities as ‘criminals’, forcing them into demarcated settlements and unpaid hard labour, Devy explained.

“Neither varna was created by any law of those times, nor was jaati created by law, or language, or sects. But a new social category did get created by enactment of law,” Devy said.

This draconian law, he added, drew from Thuggee and Dacoity Suppression Acts of the 1830s, enacted by the East India Company largely to “disarm Indian soldiers”.

Traditional coin-making communities like the Meenas, who are today classified as Scheduled Tribes, were among the victims of the CTA. “The British wanted to take over the function of making coins,” Devy said, and the way to do it was by dubbing “traditional metallurgists” as counterfeiters. The Act also targeted transgender people.

Though the law was finally benched in 1952, ‘denotifying’ these tribes, the damage had been done.

Nearly 80 years of suffering left them with “no land, no social status, and rudimentary level of literacy.” Many members of these tribes still have no residential address, which means they neither have identity cards nor, in turn, the right to vote.

Today, “an estimated 11 crore people” fall under 198 DNTs, according to Devy, who founded the Denotified and Nomadic Tribes Rights Action Group with writer and activist Mahasweta Devi in 1998.

“From today on, when you travel on any Delhi street, look at any square — those children selling balloons or any stuff every day. When we absolutely cannot help, (we) immediately pull up the glass of our cars and shut them off from our conversations. All of them are denotified,” he said.

‘Segregated’ tribes, silenced languages

Another social category that was created by the stroke of a single legislation were the Scheduled Tribes, which today make up roughly 9 per cent of India’s population.

Devy traced the existence of the tribal population to the British “creating their own forest” in India out of autonomous areas that didn’t fall under princely states or in the jurisdiction of the East India Company.

“All such places which didn’t come under the state structures in India were declared as a forest by a single legislation,” he said.

Under the Indian Forest Act 1865, inhabitants of forest communities were forced to pay a fine to British authorities for the privilege of cultivating the land and using jungle resources. “Even today, the tribes are paying fine to forest officials for the right to cultivate the land,” Devy said.

The British went on to assign morally charged classifications to these communities based on their perceived attributes, influencing how they were perceived and categorised even after independence. Those who demonstrated the “characteristics of pastoralists or nomads” ended up as de-notified tribes in the Indian republic. And those who stayed in the forests and “didn’t allow kings to dominate them” eventually became the adivasis.

“Law segregated caste and tribe in this country. Law segregated nomadic and de-notified tribes,” Devy said, highlighting the lasting impact of legal decisions on the social fabric of India.

The intense lecture had its share of light moments too. When Devy wasn’t able to provide the latest statistics on the communities under discussion, he joked that the “census has gone on a sabbatical”. On the subject of ST faculty posts remaining vacant due the lack of “competent” candidates, Devy took a swipe at the term “merit” as a “spiritual and metaphysical word accrued by the collection of punya (righteousness)”.

The room burst into laughter but returned to a more sombre mood when Devy pivoted to the precariousness of the tribal communities’ livelihoods and languages.

Stressing the unique worldview held by each language, Devy highlighted the linguistic richness within them. The Banjaras, a nomadic tribe, have a treasure trove of over 60,000 poems in the Gormati language, while the Sansi community speaks Bhatu, with trade terms dating back to Harappa and Mohenjodaro.

However, between the 1961 and 2011 censuses, more than 200 languages were ‘lost’, Devy said, hinting at the silent disappearance of languages spoken by the marginalised.

When an audience member asked how many speakers a language needed for recognition, Devy said the home ministry had deemed the number to be 10,000. He then pointed out that one language is a “perennial exception” to this requirement. When the audience whispered “Sanskrit,” he replied: “You said it, I didn’t say it.”

Also Read: Educator & watchmaker David Hare made Bengali classrooms ‘secular’ in 19th century

‘K-shaped development’

The fate of 9 percent of Indian tribals, roughly 11-12 crore, is marked by “branding, social stigma, loss of language, and loss of lives”, Devy said, underscoring that this number parallels that of the de-notified population.

He also drew attention to the plight of coastal communities who have been barred from fishing in the sea. “Particularly the deep sea has been sold to private companies and the coastal communities, fishing communities that make nets and work with boats have all migrated inward,” he said.

Altogether, Devy noted, various marginalised tribal, nomadic, and coastal communities constitute 35-40 crore people, but we are still far from having laws that can “free us and make us an equal society.”

Devy described India’s development as “K shaped”, where one branch rises and the other droops down.

“Where is the dream in India for these 40 crore people?” he asked. “Is law responsible in some way? And if it is then is it our responsibility to do something to alleviate the suffering of these people?”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

Before British, the areas dominated by tribals were theirs. They had their autonomy in those space where they lived. But when the British came they formalized the administrative system and brought every land to the purview of taxation. The caste based society adopted their format of ruling and started to do what British were doing, exploiting resource. Angrezon ghar chhina aur caste based society pura kapda chhine ki kosis Kar raha hei.