Imagine a Scotsman trying to guard young Indian students in classrooms from the influence of Christian missionaries. Or convincing conservative Bengali Hindu families in the early 19th century to give their children a modern education. David Hare did both, but few outside of West Bengal remember the pioneer of modern education in India.

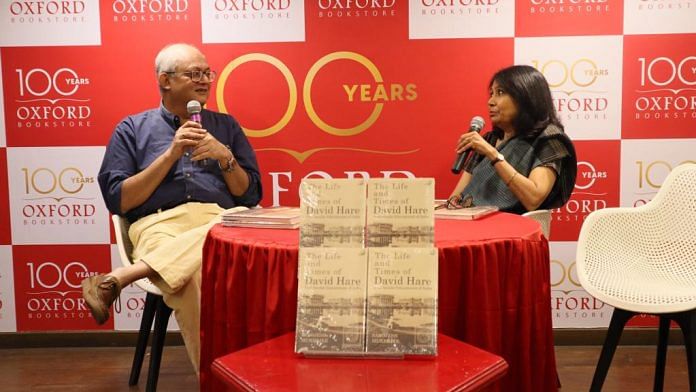

Author Sarojesh Mukerjee aims to bridge the knowledge gap in his book, The Life and Times of David Hare: First Secular Educationist of India. In a conversation with historian Rosinka Chaudhuri during the book launch at Kolkata’s Oxford Bookstore last week, he reminded the audience that Hare was instrumental in founding the Hindu College. It later came to be known as Presidency College and is now Presidency University. Another institution he helped establish was the Calcutta Medical College.

But Hare did something more remarkable than founding modern colleges: He kept religion outside the classroom. And in that process, he befriended reformers such as Raja Ram Mohan Roy and conservative Hindus like Radhakanta Deb.

“He had great respect for Hindus and was vigorously opposed to both proselytisation and interference in their customs and ways of life. In an age of religiosity and religious conflicts, he stood as a bastion of secular education,” Mukerjee said.

Also read: Pranab Mukherjee book launch had a glaring absence — Congress leaders

The secular educationist

In the 19th century, secularism was linked to stemming the growing influence of Christian missionaries such as William Carey and John Clark Marshman who opened the first organised schools in the Bengal province.

There were, of course, pathshalas for Hindus, Sanskrit tols, Persian, Christian missionary, and Arabic schools. The British were not really interested in improving the standard of education in Calcutta or the rest of the country.

“David Hare, a Scottish watchmaker who had come to Kolkata in 1801 to make a living for himself, changed all that. He ended up giving Indians modern education that kept religious dogma outside the classroom,” said Mukerjee.

Hare came to Calcutta when he was only 25. And though he became successful early on, he gave it all up. “He donated land for Hindu College, sold land very cheaply for Sanskrit College, and kept on disposing of properties that he had brought from the profits of his business to fund his schools and charitable activities,” Mukerjee said.

Hare gave away so much to the cause of modern education for Indians that he faced a severe cash crunch and had to part with his house and work as a commissioner in the court of requests for the last two years of his life.

Shunning the limelight

Launched by Rosinka and author Amit Chaudhuri, The Life and Tims of David Hare details how the educationist brought about a revolution by being a friend of India and Indians.

What struck Chaudhuri about the book was its subtitle.

“In the early 19th century, no such [school] existed in Calcutta or elsewhere in India,” said Mukerjee.

Himself an educator in Kolkata, Mukerjee was naturally drawn to Hare and his legacy. But it was only when he began researching that he realised how fascinating the Scotsman was.

Amit Chaudhuri said there was no one better to write the book than Mukerjee, who founded The Cambridge School in Kolkata and whose four generations of family members had grown up in the same 150-year-old home in the city.

“This city needs more Sarojeshs,” said Chaudhuri.

Like his biographer, Hare established deep roots in the city but avoided publicity. Mukerjee quoted historian Susobhan Sarkar, who had pointed out that Hare was so reticent about himself that after nearly 50 years of spending such an eventful life in Calcutta as a public figure, nobody even knew the names of his parents.

Once asked to sit for a portrait, Hare wrote: “Were I to consult my inner feelings, I should refrain from complying with your request. It has always been a rule with me never to bring myself into public notice.”

Hare died as he lived—without pomp. When he had an attack of cholera, then a fatal disease, Hare asked his friend Mr Gray to prepare a coffin for him. He also asked the doctor attending to him not to apply the mustard poultices again as he wanted to die in peace. “One June 1, 1842, the next day, Hare passed away. In death, as in his life, he had taken care to call the least attention to himself,” writes Mukerjee.

When the time came to bury him, the Christian burial grounds in the city were unavailable. Hare was not a believer. His final resting place became the compound of what is now Presidency University. “The tomb was paid for with money raised by Hare’s friends, mostly Indians, and students,” said Mukerjee.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)