It was early 2001. The Kashmir Valley was burning when theatre actor and director MK Raina went there to hold acting workshops and work with artists who had been threatened by militants against performing.

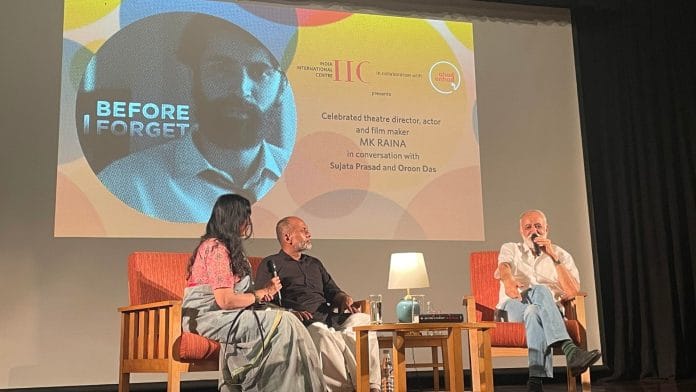

“They had not performed for 10 years. When I met them, they were crying and howling. Tears were rolling down my eyes too,” Raina recalled during a talk on his recently published memoir, Before I Forget at the India International Centre on 29 May.

The CD Deshmukh Auditorium was packed with listeners eager to hear the theatre luminary. The talk was moderated by Sujata Prasad and Oroon Das, representatives of the Ahad Anhad society.

Reviving Bhand Pather

Raina’s workshops in the Valley from 2005 to 2012 were instrumental in reviving the traditional folk drama of Kashmir, called Bhand Pather. ‘Bhand’ means actor or performer and ‘pather’ means ‘to play’. The militants banned these performances because they deemed them “un-Islamic.” But Raina was determined to breathe life into the Valley’s culture.

“I had to enter quietly or else they would have shot me dead,” he said, recounting his entry into Kashmir.

At the time, colleges and universities were shut and no auditorium was functioning. But hope emerged in the form of a hostel in an agricultural university deep inside the forest. On his friend’s advice, Raina started taking theatre workshops there.

“I called it the Gandhian way of living. We cooked, cleaned dishes, and washed our clothes,” he said.

On the day of the show at Srinagar’s Tagore Hall Auditorium, Raina recalled how two buses filled with people arrived from across the districts to watch it. “I took it as a sign that I am doing something right,” he said.

Also read: ‘Mt Annapurna’s baby’, Anurag Maloo is ready to climb again, a year after avalanche & coma

Theatre is therapy

For Raina, it was not just about art. By working with communities that have endured trauma, he intended to introduce theatre as a “healing tool”.

For another theatre performance in Jammu, Raina brought together children from Kashmiri Pandit and Muslim households of the Valley.

This decision was criticised by many of his associates and friends. People were scared that the children might hold anger and hatred for the other community.

“Children were traumatised. They used to faint while talking. Most of them had seen their fathers being shot dead. Those 50 kids were proof that the society has undergone psychological damage,” he said.

Raina was aware that typical drama training wouldn’t work in Kashmir, so he would always take a child specialist and an educationist along with him. Later, he requested his friends from the Valley to put him in touch with some mothers or women who had lost their husbands.

“I knew they would become a cushion when everything fails and it turned out to be true,” he shared.

The women would sing songs for the children, provide care, and intervene whenever two kids didn’t get along. Eventually, the children were able to let go of their fear.

This wasn’t the first time Raina was promoting art in a zone of conflict. “I was caught in cross-firing, stone-pelting, fire, police raid, threats, and so on. Nothing broke me because I knew my heart was in the right place,” he said.

One of the audience members questioned Raina about not including pictures in his memoir, leaving the audience in splits.

Raina cheekily replied that it impacts the reading experience. “Focus gadbad hota hai. I’ll release another book, which will only be pictures. I won’t write anything.”

Also read: 50 yrs of Meghalaya history, 6000 photos were trashed. A Northeast archive rescued it

Future of theatre

Raina has produced over 130 plays, including Kabira Khada Bazaar Mein, Karmawali, Lower Depths, Pari Kukh, Kabhi Na Chooden Khet and The Mother.

According to him, theatre can be an agent of change, and he is hopeful for the future.

He stated that the upcoming generation of artists is different; they are “raising questions and searching for answers.” They may not agitate on the streets like it was done in the 1960s, but “they are political thinkers.”

He pointed out how theatre workshops are happening in Delhi frequently and they are packed with people as if it’s “Nauchandi ka mela”.

“East Delhi is becoming a hub of such talented folks, who are eager to bring out stories,” Raina said.

He shared how he voluntarily visits them, watches their work, and offers whatever help he can. Although they come from different strata of society, their synergy is amazing. Raina has high hopes for the future of theatre not just in Delhi but also in Kashmir.

“I wouldn’t be able to function for this long If I didn’t keep my hopes alive,” he added.

(Edited by Prasanna Bachchhav)