New Delhi: Kanhaiya Mittal has gained fame in Uttar Pradesh for his song “Jo ram ko laaye hain, hum unko layenge.” The song glorifies the construction of the Ram Mandir. With a YouTube following of almost 3 million, Mittal has emerged as one of BJP’s most prominent campaigners, thanks to ‘Jo Ram ko…’. And now Mittal and others like him whose songs have given reach and popular voice to Right-wing politics are the subject of a book titled H-Pop: The Secretive World of Hindutva Pop Stars.

In 2022, when Yogi Adityanath secured his second term as UP chief minister, Mittal, originally from Chandigarh, was awarded a cash prize of Rs 51,000 by Yogi, writes journalist Kunal Purohit in the book. During the elections, his song became BJP’s unofficial campaign slogan. However, the singer promptly returned the prize, Purohit writes, expressing his desire to donate it back to the UP government. “Buy a new bulldozer with this donation,” he had said. The bulldozer has become emblematic of BJP’s aggressive political tactics, particularly in Uttar Pradesh.

Mittal is among the rising stars of Hindutva pop, a burgeoning form of popular culture in India that employs acerbic lyrics to celebrate the ideology’s narratives. And the genre is both lucrative and attractive, offering significant rewards.

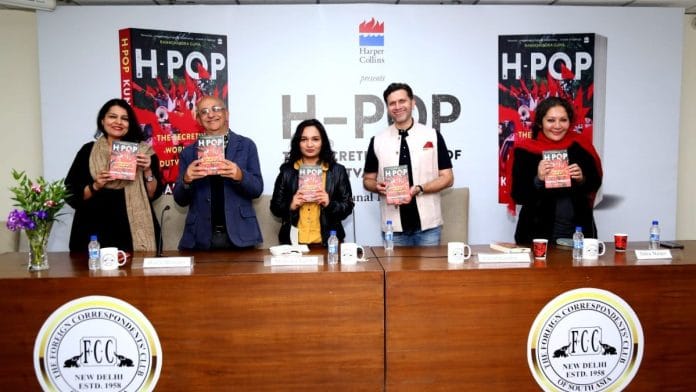

Purohit explores this new phenomenon through the lives of three Hindutva pop stars from northern India. Speaking at a panel discussion on his book at the Foreign Correspondents Club, in Delhi, along with Newslaundry editor and panel moderator, Manisha Pande, activist Harsh Mander and journalist Saba Naqvi, Purohit said, “Hate is attractive in this ecosystem. The Right wing has made it rewardable.”

Also Read: Ram Aayenge is the new Ayodhya anthem. But race to sing at Ram temple opening heating up

How music fuels mobs

Purohit was on a reporting assignment in Gumla, Jharkhand in 2019, when he first took note of these songs. Local residents told him one such song had been a catalyst for the mob lynching of Mohammad Shalik in 2017. 20-year-old Shalik was tied to a pole and beaten for hours for allegedly being in love with a Hindu woman.

Eyewitnesses told Purohit that while Gumla earlier boasted of a syncretic tradition where the Jama Masjid would be opened for the Ram Navami procession revellers to take a break, in the recent decade, things had taken a nasty turn. But in 2017, the procession was playing a particularly provocative song, along the lines of “Mulle ki topi phenk do.” (throw the Muslim’s skull cap to the ground). Later that night, Shalik was killed. Many of the perpetrators were his neighbours.

This music, permeating streets, concerts, public transportation, and even phone ringtones, can transform processions into violent mobs when combined with hypnotic rhythms and group dynamics, said Purohit.

The audience, mostly students and journalists, agreed. At one point, an audience member asked how H-pop which sounds similar to K-pop is so ‘unsexy’ in its appeal. Purohit and the audience laughed. “Perhaps, because it is used to radicalise,” Purohit answered.

Another questioned Purohit’s privilege as a Hindu journalist—Would he have been able to do his reportage had he been a Muslim? “I know that I carry the privilege of being a Hindu journalist and I don’t take that privilege lightly. Because these are spaces that Muslim journalist friends, no matter how brilliant they are, may not be able to enter,” he said.

But Naqvi retorted that his “presumption was a bit patronising”.

She said that while it may be difficult for some Muslim journalists to access, to say that they cannot do it today would be presumptuous because they continue to do so, often taking more risks than others.

Purohit countered by saying that perhaps if a Muslim had asked Kavi Singh or Agney the questions he did, they would have refused to answer.

Both eventually concluded that it is the story that matters, not the reporter. “The story is much bigger than all of us”, Purohit said.

Purohit’s observations shed light on the type of content, mindset, and ideology prevalent within the Hindutva ecosystem. Topics such as Article 370, love jihad, and stereotypes about Muslim population growth are recurrent themes, along with mentions of Bollywood figures like Shah Rukh Khan and his son Aryan Khan, as well as the other Khans.

Also Read: After viral Pulwama song, Kavita Singh flopped. It took ‘Ram chant in Kashmir’ to revive her

The profitability of hate

One of the three central figures in Purohit’s book, Kavi Singh, a 25-year-old woman from Haryana gained prominence with her song Dhara 370 following the abrogation of Article 370 and 35-A in Kashmir. Kavi’s songs cover a wide range of topics, from love jihad to Pulwama, with lyrics such as: “Dushman ghar mein baithe hain, tum kos rahe padosi ko. Jo choori bagal mein rakhte hain, tum maar do us doshi ko” (The enemies are sitting at home, but we blame the neighbour. The one who carries the knife beside you, finish off that culprit).

“These narratives perpetuate old prejudices and biases”, Naqvi said.

Even Gandhi is not spared.

Kamal Agney, a 28-year-old poet sympathises with Godse in his recitations at poetry gatherings, both online and offline, where he glorifies Gandhi’s assassination through verse. “Hindu armaano ki jalti ek chitaah the gandhiji Kaurav ka saath nibhane wale Bhishma Pitamah the gandhiji (Gandhi was the burning pyre of Hindu aspirations, he was the Bhishma Pitamah that sided with the Kauravas)

“Gandhi’s talk of non-violence and love and morality are seen as signs of feminine behaviour. It is not a sign of masculinity,” said Mander in response to Pande’s question about why Gandhi troubles the Right wing.

He then shared an anecdote about how when Richard Attenborough’s Gandhi was shown in Delhi schools as part of a project, the scene of Gandhi’s assassination was cheered on by the children.

The third figure in the book is Sandeep Deo, a journalist and YouTube influencer, who aspires to supplant the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party with his own party comprising Hindu warriors well-versed in both shastra (Vedic knowledge) and shastra (weaponry). Deo likens himself to a frontline warrior who is waging a cultural war ‘against mainstream media to the West to Islam to Netflix’.

All three have a common playground—the digital media space. The Hindu Right has utilised this digital proliferation like no one else.

“We have a data revolution in India where we don’t have atta but we have data. And everybody has a phone in their hand. There’s this technology and there is this whole profitability of becoming a foot soldier. You belong to something,” Naqvi said.

This belongingness now transcends traditional identity markers. It’s illustrated by the H-pop artistes’ refusal to identify themselves by caste, as Purhit recounted. “They assert their identity solely as foot soldiers of Hindutva, rejecting any divisive categorisation,” he said.

But Purohit warned that equating anything communal with the BJP and RSS is a “lazy, liberal analysis”.

He added that while we can’t discount the ideological commitment, there is a more sinister development happening. “They are also realising that hate can be extremely rewarding and sustainable as a model,” he said.

It is perhaps why Mander said at the end of the talk that Purohit has dedicated his book to his country that’s “increasingly unrecognisable”.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)