New Delhi: Seventy years after Jawaharlal Nehru established the Indian Institute of Public Administration in 1954, his economic legacy was subjected to a litmus test at one of the institute’s lecture halls.

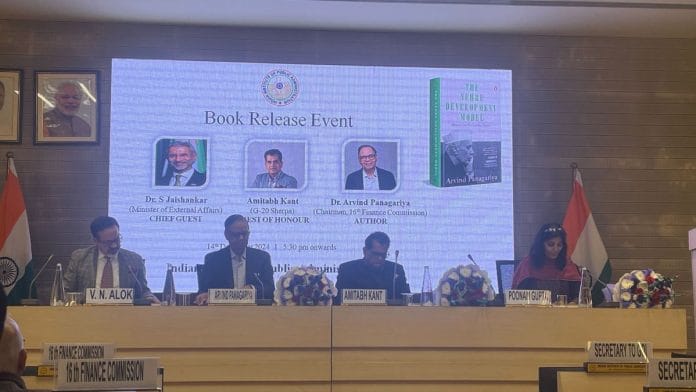

The occasion was the launch of a new book, The Nehru Development Model. Author Arvind Panagariya, chairman of the 16th Finance Commission, stood on the podium for about 45 minutes, dispassionately dissecting Nehru’s economic thought process, the implementation of his plans and finally, the lasting impact of his policies.

“Nehru’s objective was to use industrialisation and growth as instruments of combating poverty,” said Panagariya. “On this, he gets it completely right. What he doesn’t get right is the model itself.”

Panagariya was joined by India’s G20 Sherpa Amitabh Kant, IIPA professor VN Alok, and PM Economic Advisory Council member Poonam Gupta.

Minister of External Affairs S Jaishankar, scheduled to attend the discussion as chief guest, couldn’t attend due to a commitment with Prime Minister Narendra Modi. While his absence left many audience members disappointed, Jaishankar compensated with a video message expressing support for Panagariya’s latest work.

The lecture hall was filled with professors, economists and members of the finance commission. A few passionate students, many of whom were enrolled at IIPA, clutched copies of the newly launched tome in hopes of getting a signature from the distinguished author.

According to Panagariya, Nehru wanted to figure out what the consumption needs of the country were and then re-jig the production baskets accordingly.

“Nehru wanted self-sufficiency,” said Panagariya. “He reasoned that trade had been an instrument of spreading imperialism by capitalism.”

The verdict was clear: The first Indian prime minister’s intentions were noble. It was his execution that failed to achieve the desired objectives.

Nehru’s view on growth

Jawaharlal Nehru’s socialist stance frightened many industrialists at the time. “He wanted the means of production to go to the public sector so inequality would not rise,” said Panagariya.

The prevailing thinking at the time was that investments brought growth – which in turn required machines.

“His [Nehru’s] reasoning was that we have to start producing machines first otherwise we can’t do any investments,” said Panagariya. “The heavy industry becomes the centrepiece of his model, which turns out to be the biggest mistake [he made].”

The economist backed his assertion with data points.

“India had a low GDP, a savings rate of 7 per cent and so investable resources were very small. If you go straight into heavy industry, which is capital intensive, it will absorb virtually all of your capital.”

The second five-year plan did just that, he said. Three steel mills were built up along with a couple of machinery factories, all very capital-intensive endeavours.

Also read: Nehru wanted India to develop a scientific temper. Today’s leaders are doing the opposite

Licence Raj ‘throttled everything’

Amitabh Kant was less forgiving.

“During Nehru’s time, India got caged by slow economic growth when the rest of the world was expanding,” declared Kant, who once worked with Arvind Panagariya at NITI Aayog (February 2016 to August 2017).

He took a much more passionate approach when bemoaning India’s lost opportunities. His voice boomed across the room as he spoke about the various acts of the Licence Raj – a period between 1947 and the early 1990s that was characterised by excessive government regulations.

According to Amitabh Kant, the Industrial Disputes Act of 1947 was a direct result of the socialistic pattern of society at the time, when labour rights were high on the Nehru government’s agenda. He gave the example of Kerala’s fisheries sector, recalling his experience with a corporation that had about three thousand workers.

“I tried to terminate some of them, and not only did I face strikes, but I learned that it was impossible to retrench anyone under these Acts.”

Kant’s frustration was clear throughout his speech, a stark contrast to Panagariya’s reserved approach.

“This whole trend of nationalising and putting Factories Act, Labours Act, Wages Act just throttled everything,” said Kant. “It throttled enterprise, the spirit of India, the spirit of production and the spirit of productivity.”

Nehru’s investments in human capital have yielded long-term benefits to India, Kant stressed. “His commitment to secularism and pluralism has influenced India’s constitutional framework, but on the economic policy front, his legacy is highly debatable.”

He went on to provide some solutions for India to reach its full potential.

“If India wants to grow, we need to take the population away from agriculture and into industries…You cannot grow with 46 per cent of your population in agriculture.”

Kant then emphasised the need for urbanisation. He even called on the members of the 16th Finance Commission (including chairman Panagariya) to enact reforms on this front.

“States must be penalised for not driving urbanisation. It’s the finance commission’s critical job to undo many of these legacies of Nehru,” said Kant, who was buoyed by the crowd’s laughter and desk-thumping applause.

The former NITI Aayog CEO even turned directly to Arvind Panagariya and half-jokingly said: “There’s no point writing a book, you must translate it into delivery through the 16th finance commission.”

Also read: Nehru is like a wall that never breaks despite some people’s efforts: Manoj Jha at book launch

Lasting impact

Once Nehru put his socialist policies in place, a narrative had formed – and it influenced everything else that followed. Socialism is built into our DNA, said Panagariya.

“India was put on a deterministic path, from which retreat became nearly impossible.”

In a recorded message, Jaishankar echoed the author’s thoughts.

“The [Nehru] model and its accompanying narratives permeated our politics, bureaucracy, planning system, judiciary, media and most of all, teaching,” the MEA said.

According to him, both Russia and China unambiguously rejected the economic assumptions of that period, even though they enacted these principles more than anyone else.

“Yet these very beliefs live on in the influential sections of our country, even today,” said Jaishankar. “After 2014, there has been a vigorous effort towards course correction.”

Panagariya gave more concrete examples of how the reverberations of Nehru’s model are felt even today.

“There is an inheritance of ideas from one generation to the next…For youngsters, socialism is such an attractive philosophy. How can you be against more equal income distribution?”

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)