New Delhi: From being a potent symbol of Bengal’s nationalist struggle to being used for selling baby food, cigarettes and matches, the image of goddess Kali is deeply entrenched in India’s socio-political and cultural fabric. However, the goddess’ popularity has extended beyond the country’s borders. Introduced to Europe by the British, her iconography grew steadily over the years – along with her irreverence and appropriation.

‘Kali: Reverence and Rebellion’, an art exhibition curated by Gayatri Sinha, gives us an overview of the diverse representations of Kali and the many meanings attributed to her from the 19th to the 20th centuries. Early Bengal oil paintings, sculptures, body ornaments and curios make up this unique collection, which is currently on display at the Delhi Art Gallery (DAG) in Janpath.

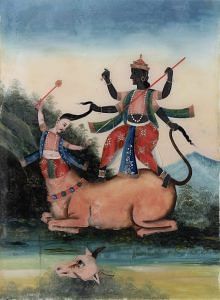

Kali assumes many forms even within India. In Bengal, she is the benevolent and blue-skinned Dakshinakali, whereas in Kerala and North India, she is the powerful Bhadrakali and the vengeful Chamunda. These varied representations have been modified, re-imagined and re-created by artists – known and unknown – across geographies, languages, castes, and political ideologies, adding richly to the contexts they were conceived for.

Western perception

Eventually, international artists took a keen interest in the goddess and created their own interpretations. These, however, were not always reverential. “From the 1830s, publications like George Bruce’s The Stranglers: The Cult of Thuggee and Its Overthrow in British India along with popular films like Indiana Jones: The Temple of Doom [1984] fixed Kali’s association with thugs and thuggery in the wider (Western) imagination,” wrote Sinha in her book, Kali: Reverance and Rebellion.

Russian artist Prince Alexis Soltykoff painted ‘The Procession of Kali’ in 1840. It depicts a nocturnal procession of the goddess, where her ‘army’ is engaged in song and dance. Her neck is adorned with a necklace of skulls, while she holds severed heads in two of her hands. Another hand clutches a giant sickle, while one remains open in the abhaya mudra – a hand gesture symbolising fearlessness. The painting provides a glimpse into the negative and criminal perceptions created and circulated by the British about not just Kali but the ‘lower caste’ and fringe communities that were later listed under the Criminal Tribes Act 1871.

These White perceptions were directly challenged by the nationalist ideology taking root in India at the time. It portrayed Kali as a vanquisher of evil – an iconography that came to be widely used. One example is a poster of Subhash Chandra Bose depicted in Chhinnamasta iconography. This poster was published in the 1940s by National Press Kanpur, utilising offset and serigraph printing techniques on paper.

A painting of a bare-breasted Kali, standing atop Shiva on a cremation ground and garlanded with severed heads of Englishmen, accompanied a report outlining ‘political troubles’ in India between 1907 and 1917. James Campbell Kerr’s ‘Political Trouble in India 1907-1917’ was an insight into the use of Kali iconography to instil nationalistic fervour among Indians.

Also read: Chikankari workers stood up to maulvis during Shah Bano protests—art gave them courage

Cultural exchanges, pop culture moments

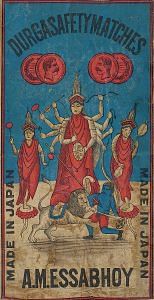

Matchboxes featuring Kali’s Mahisasurmardini avatar were also featured in the DAG exhibit. It was part of the trading exchange between a Parsi firm named A.M Essabhoy and their office in Yokohama, Japan. They combined Hindu gods and goddesses with Japanese aesthetics to create unique iconography that became popular across Europe and Japan and ensured more matchbox sales for Essabhoy.

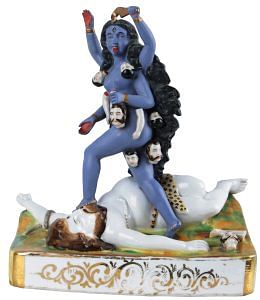

Catering to the demands of India’s urban markets in the early 20th century, Germany started making porcelain figurines of Hindu deities. Inspired by European interior design, Bengali upper-class Hindu families would buy and display them in glass cabinets. From Dakshinakali and Tara to Krishnakali Mata, various versions of Kali were used to make these figurines. One standard element in nearly all of them was the palms of the goddess, which were mostly smeared with vermillion.

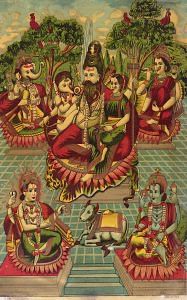

A painting titled ‘Shiv Panchayat’ shows Shiva holding a young Ganesha, with his wife Parvati seated on his lap and Brahma and Vishnu seated before them. An adult version of Ganesha and Lakshmi stand behind, while Nandi rests before all the figures. This chromolithograph, printed in Italy, shows how fascinated the West was with Kali and her myriad forms, and the profitability they brought with them.

Meanwhile, some 19th-century ‘Reverse Glass’ paintings from China show a blue-skinned Jagathdarini, and a Mahisasurmardini holding the decapitated head of a distinctly East Asian Mahishasur.

This fascination has only grown stronger in the years since, often accompanied by controversial representations and appropriations. In 2015, an image of Kali was projected onto New York’s Empire State Building to create awareness about climate change and nature’s wrath. However, the use of this iconography enraged Indians, who found it highly inappropriate and disrespectful.

Singer Katy Perry was slammed in 2017 for sharing a tweet with a photo of goddess Kali and captioning it as ‘current mood’. Before that, German-American supermodel Heidi Klum had dressed up as Kali for Halloween.

The poster of Tamil filmmaker Leena Manimekalai’s documentary Kaali (2022) also created huge controversy upon being tweeted. The poster showed a woman dressed up as the goddess and smoking a cigarette. This image is set against the rainbow flag of the LGBTQIA+ community.

Regardless of the era, Kali continues to evoke awe, inspiration, curiosity – and controversy.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)