New Delhi: Art is not limited to an oil painting chained on a wall or an installation in a gallery. It can spark change – whether through a group of women chikankari workers sewing and talking about the Shah Bano case, or displaced women converting a session on patchwork cushions into a thriving business.

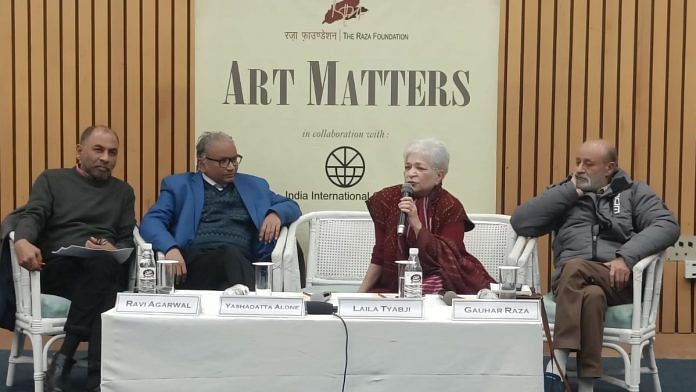

“Through craft, you can create a new dynamic in society. This is much more than a means to earn,” said Laila Tyabji, social worker, craft activist and founder of the collective, Dastkar. Her experience over decades set the stage for the 89th session of Art Matters, a platform by the Raza Foundation which explores the intersection of literature, politics, social justice poetry, and the arts. The theme for the latest session, ‘Art as Social Action’, held earlier in January at Delhi’s India International Centre, explored the intersection of the two seemingly disparate worlds.

“Nobody thinks of crafts persons as professionals who are as skilled as all of us, or maybe more skilled. To set an Ikat loom requires as complex mathematics and brain power as to do computer programming. But somehow, one is somewhere in the background and the other is recognised,” said Tyabji while in conversation with Jawaharlal Nehru University professor YS Alone, Urdu poet and scientist Gauhar Raza, and photographer Ravi Agrawal.

Finding agency through craft

Tybaji recalled her time in Rajasthan in 1980, with people from 14 villages who had been displaced from their homes in what is now Ranthambore National Park. What remains largely unknown, she said, is the story of these people who were uprooted from their ancestral homes to pave the way for this conservation effort.

Initially, the village women rebuffed Tyabji’s efforts to interact. So she sat down to craft a patchwork cushion in her room – a simple yet powerful invitation they accepted one by one. But one woman, a Dalit, peered hesitantly through Tyabji’s window, unsure of whether she would be welcomed. After an invitation to come in for tea, she finally joined the group.

“Today, these same women who did not talk to each other now travel together across India to sell their craft. This year, their annual profit was Rs 200 crore,” Tyabji said proudly.

She had a similar experience during protests against the Supreme Court’s ruling in the Shah Bano case, which upheld a divorced Muslim woman’s right to maintenance. Tyabji was collaborating with women chikankari workers in Lucknow at the time. During a sewing session, they revealed their plans to join a protest march against Shah Bano, after being prompted by their husbands. While they sewed and stitched, they discussed marriage and equality and women’s rights. Instead of attending the march against Shah Bano, the women organised a countermarch, said Tyabji.

“Men did not realise that we were creating activists—sitting on the floor, doing the most feminine thing.”

Also read: Ukrainian pianist mixes music, Putin and history at Delhi jazz club. His mission political

Recognising craftspersons

The panellists challenged prevailing “casteist narratives” that confine art to the sacred and divine. While on her way to IIC for the discussion, Tyabi learned that Abdul Rahman Khatvi, a talented ajrakh block painter who became the youngest recipient of a National Award at 25, had passed away. He was only 48 years old.

“Had he been a writer or a mainstream artist or a performer, he would have been noticed. But he fell in the category of ‘art person’. Nobody thinks of crafts persons as professionals who are as skilled as all of us, or maybe more skilled,” said Tybaji.

If art is an instrument of war—as Picasso described it—it’s also a herald for change. Raza gave the example of Hum Dekhenge, a 132-word nazm by poet Faiz Ahmed Faiz, which Pakistani singer Iqbal Bano sang at a public gathering in Lahore. It was seen as a challenge to Zia-ul-Haq’s regime, but the song remains a potent anthem of dissent—its notes were picked up in India, and diaspora in Germany, Italy and the US during the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) protests in 2020.

While his reference pointed to Hum Dekhenge, Raza never explicitly mentioned the song. “You know which song I’m talking about?” he asked. “Why does it happen that art forms never die? Those in power know the maar (impact) of a song of mere 132 words,” he said. “Your being present here matters and a painter’s painting matters. Art matters.”

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)