New Delhi: The gypsies in Enid Blyton’s books, in Victor Hugo’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame, or in the British drama Peaky Blinders might be descendants of an ethnic group belonging to the Indian subcontinent. The Roma, also known as Romani people, emigrated to Europe over a millennium ago and are pejoratively called “gypsy,” a term derived from their mistaken association with Egypt. This lesser-known facet of history was the subject of an hour-long lecture by New Delhi-based musicologist, acoustician, linguist, and educator Punita G Singh at the India International Centre on 21 March.

In a conference room filled with nearly 30 people, Singh wasn’t surprised to know that only one person in the crowd—mostly comprising academicians, retired government officials, and a few foreigners—was aware of this largely obscure group. Her lecture, titled ‘The Roma Exodus and Reconnection with a Forgotten Diaspora,’ introduced the Roma to the audience and explored the group’s connection, disconnection, and efforts to reconnect with India.

Struggle for recognition

The journey of the Roma from India to Europe is shrouded in mystery and historical conjecture. Singh refrained from giving a linear answer to the most obvious question ‘Who are the Roma’. She said there are no “clear-cut answers” and “a lot of murkiness” surrounds the historical evidence. While precise origins remain elusive, various theories attempt to trace the migration of the Roma, including legends from Persian literature and historical accounts of conquests.

Singh, who integrated music with Romani studies during a semester at Ashoka University, cited several sources to establish that the Romani diaspora largely belonged to the northwestern part of present-day India. About 1,000 years ago, this region might have included areas of Balochistan, Sindh, and Multan in Pakistan.

However, the Roma migration has been far from uplifting. Even today, the group is fighting a constant struggle for recognition and against marginalisation.

“If you look at the EU (European Union) site and what they say about the Roma, it immediately begins with the Roma being Europe’s largest ethnic minority,” Singh said. “They have historically been the most marginalised, the poorest, the least educated, and underemployed.”

The linguist highlighted how the itinerant people have historically suffered because of being looked upon as ‘the other’. It is reflected in their stereotypical representation in arts and literature—as criminals or an exotic tribe that practises sorcery or witchcraft. The fate of the Roma “parallels” that of the Denotified Tribes of India in their nomadic nature, their ostracisation, and the move to settlement, Singh said.

Singh, who has mined extensive data about the group, told the audience that the Roma population is around 10-12 million in Europe. However, she added that the number could be as high as 20 million. That’s because some countries don’t include ethnicity as a factor while conducting a census. The other possibility is that many people don’t claim their Roma identity, “especially if they have become whiter from all these centuries in Europe and sometimes with intermarriage”.

Also read: Stars of Hindutva pop write songs about love jihad, Pulwama. They’re unofficial BJP anthems

Journey to Europe

Medieval sultan, Mahmud of Ghazni, the ancient city of Kannauj, and the Roma have a twisted connection. Singh said that the most compelling account of how the Roma ended up in Europe was offered by a French linguist and researcher Marcel Courthiade. His theory zeroes down on Uttar Pradesh’s Kannauj district and the conqueror Mahmud of Ghazni, by drawing inferences from his historical memoir Kitab-i-Yamini.

“Marcel calls it the Great Departure (which was) the exodus from India. Marcel talks about Ghazni arriving at the gates of Kannauj and how he took away all these prisoners and they are the proto-Roma,” Singh said.

In an excerpt from the Kannauj hypothesis, circulated by Courthiade in December 2018, he mentioned that the Sultan of the Ghaznavid Empire headed back to his homeland with 53,000 prisoners “rich and poor, light and dark”, along with 385 elephants and 16 huge chariots full of jewellery.

Another hypothesis includes a story by Persian poet Ferdawsi in Shahnameh about his emperor wishing for a thousand musicians and dancers sent from India. Additionally, genetic studies have provided further insights, establishing lineages connecting the Roma to northwest India.

“But even before all these studies and all this kind of genomics, the first clue about the Indian relationship was language,” Singh said, noting that scholars had taken up these studies in the 1800s.

Linguistic, cultural similarities

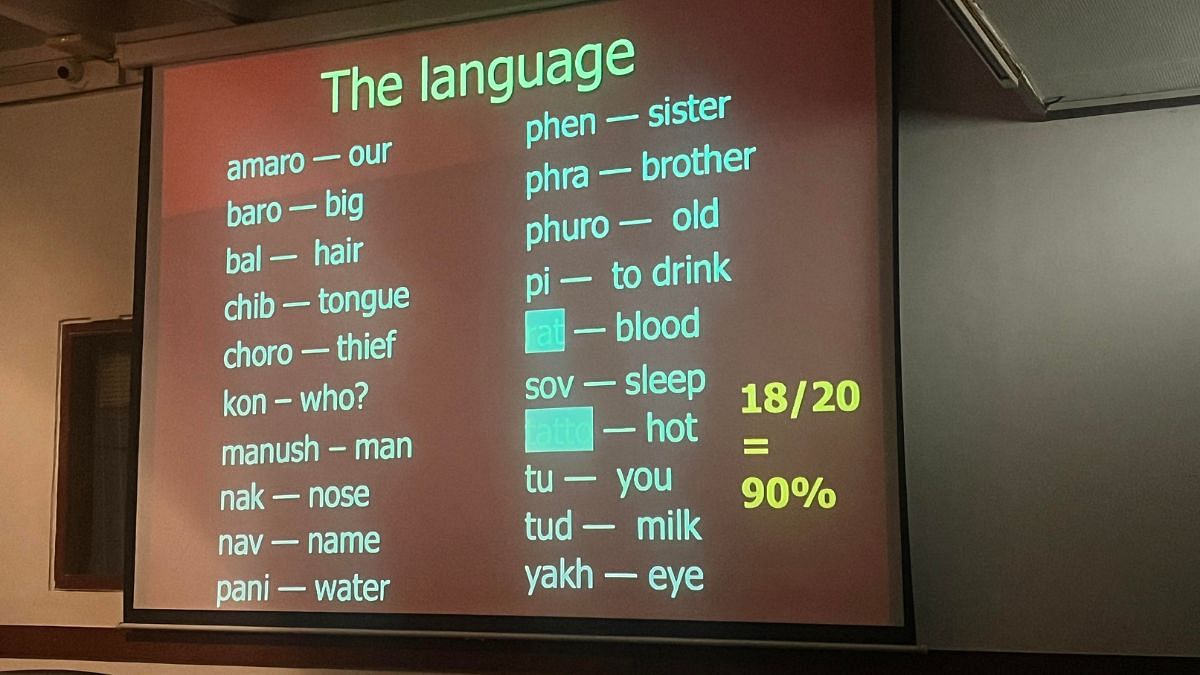

Singh’s lecture explored not only history but also language, politics, genetics, and geopolitics associated with the Roma. She kept the listeners hooked with an elaborate presentation showing slides filled with data, graphics, rare archival photos, and audio-visual elements. At one point, she gave people a pop quiz where they tried to find similarities between Romani and northwest Indian languages.

The similarity between Romani and Punjabi/Hindi words is uncanny. The audience could effortlessly understand Romani words like amaro (our), bal (hair), nak (nose), phen (sister), phra (brother) or tud (milk), all of which are present in the Punjabi language.

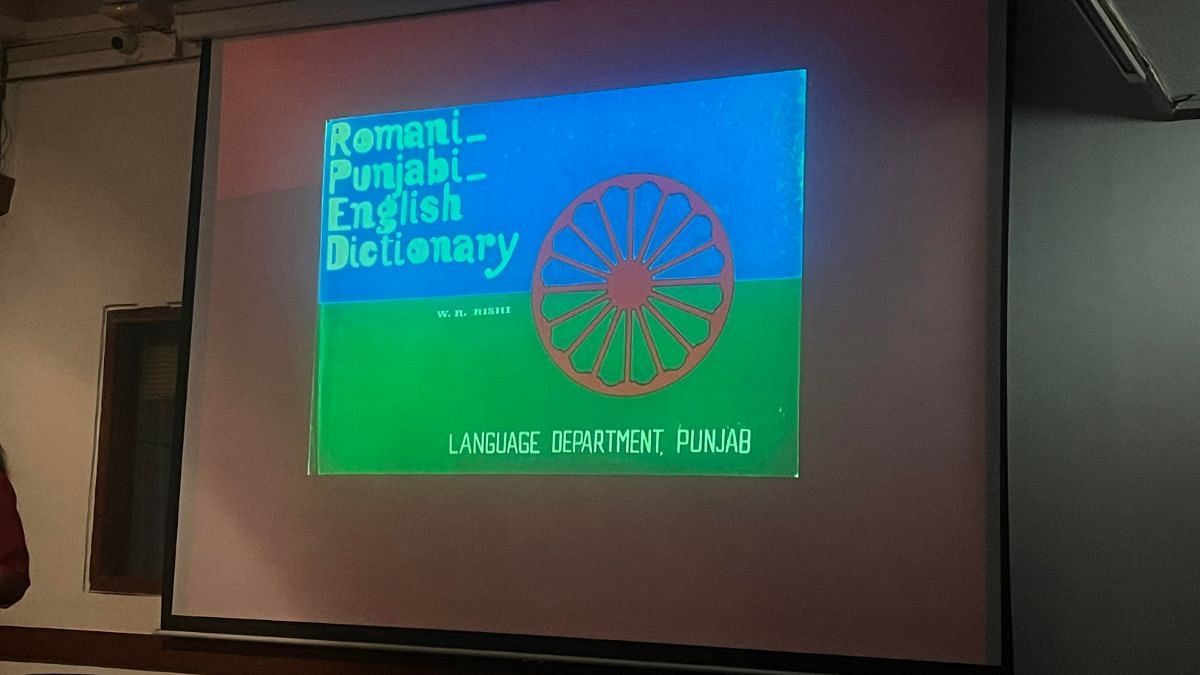

Although European scholars identified linguistic similarities between Romani and Indic languages in the 19th century, not much was happening in India until the 1970s. WR Rishi, a linguist and former diplomatic translator with the Ministry of External Affairs, made the first strides toward linking the dots from the Indian side. His job got him access to areas such as Central and Eastern Europe and the Balkans, which “in the 1970s would have been hard for any people”.

“So, he’s got access and realised that there is this kinship between the language, the culture, the people,” Singh said.

Rishi wrote a book titled Roma: The Panjabi Emigrants in Europe, Central and Middle Asia, the USSR and the Americas in 1976 and even published a Romani-Punjabi-English dictionary in 1981.

Also read: ‘Asia on the Move’ looks beyond Silk Route. Musicians, painters forged India’s ties too

Disconnect & reconnect with India

Castrated and enslaved in Romania and facing persecution during the Holocaust, the Roma have faced systemic oppression and violence for centuries. Over half a million Roma people were killed during Hitler’s extermination campaign.

Singh questioned India’s “conspicuous absence” among the 25 nations that lay wreaths every year on 2 August in Auschwitz to honour the massacred Roma. She also raised concerns about the ethnic group being missing from NCERT books, apart from a passing mention in a Class 9 history book.

“Where (did) the disconnect happen? Where did we lose our kinship with the Roma?” she asked rhetorically.

The linguist conjectured, “Maybe their story got overwritten,” suggesting that the Roma exodus was “ignored” due to the influx of other people into India.

It was only in the 1970s that efforts of the Roma community to establish “a nation without a land” got bolstered. Singh added that efforts toward recognition of the Roma and their empowerment have gained momentum in recent decades. Political advocacy at the European Union level has seen strides toward Roma inclusion and integration. On the home front, Roma people have been demanding recognition as people of Indian origin. Soon, a memorial is going to be erected in Kannauj honouring the “forgotten” community.

As the floor opened for questions from the audience, a JNU professor named Vidhu Verma came up with a list of queries—the pertinent one being whether it was important to identify people from a particular origin so that they could come back to that place. She underlined the current political climate in India where “original arguments” are being made, “telling people to go back to where they belong”.

Singh said that the place of origin is a contentious issue within the community. The small minority “with very big nostalgia” might want a land to call their own. And many of them “would still want some acknowledgment” as the Indian diaspora and be given some privileges of the “historic connection”. However, some are averse to the idea because they fear “the Europeans can use it as a tool” to say “go back to where you belong”.

In reality, the Roma community faces more pressing concerns. Singh said that the Romani “language and culture are at risk” as the younger generation is more fluent in the language of the majority and more aware of that culture than of their own.

“So, the origin is important, but not in terms of going back to where you belong. That wouldn’t work,” Singh said.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)