New Delhi: Only in Delhi will people turn up for a discussion on perfumery with their masks on. A moonlight open-air setting at the India International Centre, Annexure brimming with the scents of mogra oil and benzoin resin, could have been an olfactory symphony but for Delhi’s toxic air that overhangs.

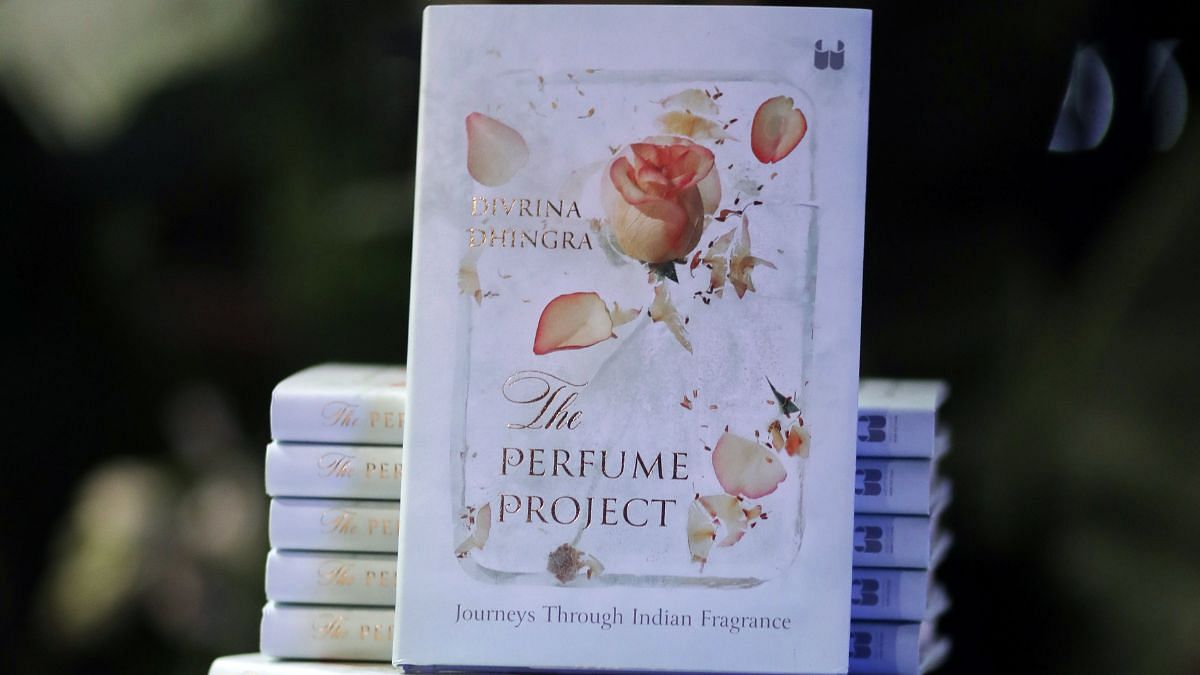

Visitors braved the smog for the Delhi launch of The Perfume Project, published by Westland Books last Thursday. The discussion between author Divrina Dhingra and oral historian Aanchal Malhotra was an olfactory symphony. The audience was transported into a world of science, history, sociology, and nostalgia surrounding perfumery. All while not losing sight of the challenges hovering over India’s perfume industry.

“This season of terrible pollution in Delhi is also the season of the best smells. There are all the evening flowers—the jasmine, the harsingar, the sampangi, which is my absolute favourite,” said Dhingra, a former columnist and journalist.

Dhingra, who studied perfumery in Europe, said it is necessary to create a detailed vocabulary of scent because in the world of aromas, merely saying that the smell is “really good or nice or pretty” isn’t going to take you very far.

“When I started training in perfumery, this became the first stumbling block because you have to memorise hundreds and hundreds of ingredients. You have to create the vocabulary in your mind for yourself when you come across it again,” she said.

This vocabulary is what makes up the core of her book. Malhotra described it as an atlas of scents that attempts to “give language to something that’s invisible and seductive”.

She also described as extraordinary the “nuanced descriptors” present throughout the book, which found their way into the evening’s discussion. “Is a rose creamy or milky? Is a rose sharp? Is it a green rose?

There are all these markers of smell and they evoke different images in your mind,” Malhotra said.

Technical terms such as ‘indole’—a chemical constituent of all white flowers—were also introduced to the audience. The author pointed out the incongruity, paradoxes and balance within the world of fragrances.

“When you isolate the indole and you smell it, it’s not pleasant. It smells to me like naphthalene balls. To other people, it smells like wet fur or garbage,” Dhingra said. Malhotra underscored this dichotomy as a reminder that “everything beautiful has some element of the ugly”.

Dhingra used musk—one of the most popular smells—as another example of this incongruence. “Musk in itself is not what it smells like in composition. Musk can smell a little faecal. It doesn’t smell great. It’s an animal smell,” she said, stressing that being able to appreciate some smells is “very much an acquired taste”.

Beautiful smell requires a fine balance of several ingredients, which she realised at the perfume school where she had to deconstruct famous fragrances.

Also Read: Rose, sandalwood, petrichor—Gulabsingh Johrimal that captured Mughals with ‘Indian’ scents

‘Itr has a marketing problem’

When the discussion opened to the audience, pertinent questions about the Indian perfume industry emerged. One audience member questioned the lack of popularity of itr perfumes, especially among those from the higher income society.

Initially, Dhingra attributed it to “personal preference”, as itr has a “very limited palate” because there are only so many natural ingredients. In contrast, synthetics are used in alcohol-based fragrances, which allows for a lot more variety.

“You can capture a mood and you can capture a day and you can do all of those things,” she said, emphasising the limitations involved with itr.

But the more pressing reason, Dhingra said, was the marketing of itr.

“People just don’t know enough [about it] or it isn’t visible in enough places. It isn’t marketed the way that big brands market their fragrances, which requires deep, deep pockets as well,” she said.

The other concern raised was regarding the future of the perfume industry, particularly due to the growing prominence of synthetic ingredients. Dhingra didn’t mince any words when she said that synthetics “can’t be dismissed”, while highlighting that they “are unfairly demonised.”

Natural ingredients are still the preferred choice but Dhingra added that because of climate change, many of these now have to be created in a lab. This increases the cost of perfume.

“The only way that you can [make] fragrance economical and a part of our daily lives [like they are] now is because of synthetics,” she said.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)