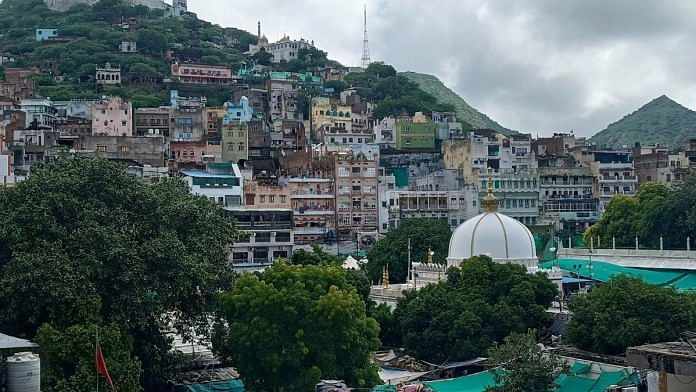

The scent of roses mixed with incense sticks snakes through the narrow, packed bylanes of Ajmer Sharif Dargah in Rajasthan like it has been for centuries. But this time, it is laced with the brewing of a strange disquiet. The 800-year-old hub of Sufism and Hindu-Muslim harmony has been in the news over the viral speeches of two Khadims, or clerics, in the wake of Bharatiya Janata Party’s suspended spokesperson Nupur Sharma’s comments about Prophet Muhammad.

One video showed the bylanes resounding with slogans of ‘sar tan se juda’ (a call to behead as punishment for blasphemy) outside the Dargah Sharif. The holy shrine until now has mostly been in the news for its VIP visits—from Deepika Padukone, Katrina Kaif, Priyanka Chopra, Kangana Ranaut to Manmohan Singh, Shah Rukh Khan, Ajay Devgn, Kareena Kapoor, Kajol, Akshay Kumar and Amitabh Bachchan.

But for the first time since the 2007 tiffin carrier-bomb explosion in the Dargah courtyard, negativity is clouding Ajmer’s storied reputation of peace.

Controversy clouds Dargah

Salman Chishti, a Dargah cleric, was arrested by the Rajasthan Police late July for issuing a bounty on Nupur Sharma. In a video of him crying, he purportedly said he will give his house to whoever beheads Sharma. In another video, cleric Gauhar Chishti is seen shouting ‘sar tan se juda‘ outside the Dargah. He, too, was arrested.

As Ajmer Dargah turned into a hotbed of hate, the footfall dipped, causing losses to local businesses in the vicinity, half of which are run by Hindus.

A year ago, another video of Sarwar Chishti, a senior Dargah cleric, had allegedly reminded Indians that Muslims had ruled this land for centuries and could do so again. This was recirculated in the wake of Sharma’s video.

The Khadims, who follow the Sufi teachings of Khwaja Moinuddin Chishti—‘love towards all, malice towards none’—find it frustrating that the Dargah has to give clarifications for what it stands for.

“A drug addict and history-sheeter calls for violence and it goes viral, and I have been going around the world representing Ajmer Sharif Dargah for the last 20 years but that will never go viral. This is the irony of today’s times,” said Haji Syed Salman Chishty, chairperson of the Ajmer Sharif Chisty Foundation. Chishty points out that “the voices of peace go unheard because maybe they are not sensational enough to generate the ratings.” He also expressed anger at the media using his photographs instead of the arrested cleric.

Sufi thought has a wide following and admiration among Indians of all faiths. In 2016, PM Modi, addressing the World Sufi Forum in New Delhi, called the faith a “light of hope…when the dark shadow of violence is becoming longer”. He even quoted Khwaja Moinuddin Chishti. But Sufism hasn’t got a universal, uncritical acceptance in contemporary India. In recent years, even a popular Sufi song such as Amir Khusrau’s Chaap Tilak was interpreted as one that cloaks the religious conversion of Hindus to Islam in the name of love.

So, the rage over the Ajmer videos wasn’t entirely unexpected, especially when a lot of inherited wisdom is being contested.

Also Read: Satanic Verses to Kaali—religion-arts binary isn’t real. Hurt sentiments staged in 3 ways

A favourite among kings and leaders

Before the videos against Nupur Sharm’s remarks surfaced, there was never any doubt about what the formidable Ajmer Sharif Dargah stood for–an interfaith place of worship that doesn’t discriminate, a site for wish-fulfilment and a pilgrimage that can’t happen unless you are called.

“Resolves are made every day, but they often fail. Only those can come to Ajmer who are called by Khwaja Sahab himself,” said Salman Chishty.

From Mughal king Akbar in the 17th century to former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, kings and leaders through the ages have sought blessings at the holy shrine. Prime Minister Narendra Modi sent a chadar to the Dargah in 2015. So did Barack Obama.

When Pakistan’s then-president Pervez Musharraf came to India to meet PM Atal Bihari Vajpayee in 2001—a visit to his birthplace in Old Delhi and Ajmer Sharif Dargah was on the cards. But the Kashmir talks broke down, and he left India in a huff. Musharraf eventually visited the shrine in 2005.

Akbar was Khwaja Moinuddin Chishti’s ardent devotee, and reportedly walked from Agra to Ajmer when his wish to have an heir was fulfilled. The anecdote makes for good drama. In the 2008 Bollywood film Jodha Akbar, Hrithik Roshan, who plays the Mughal emperor, twirls to A.R. Rahman’s lyrics Khwaja Mere Khwaja in Ajmer.

Akbar later constructed parts of the Dargah, a mosque and ‘Khanqahs’ (place of spiritual retreat) for the servants of the Dargah and gifted them its biggest degh (cooking vessel).

In 2014, Shah Rukh Khan had recounted in a promotional interview his visit to the Dargah many years ago. He recalled how, after he lost Rs 5,000 there, a fakir told him that he would one day “earn Rs 500 crore”.

So when senior Khadim Anjuman Committee secretary Sarwar Chishti’s one-year-old video about Muslims ‘ruling India for centuries’ went viral, the Dargah’s image of peace, benevolence and co-existence was severely damaged.

Sarwar Chishti condemns the slogan raising and bounties being issued—but with a disclaimer. “This should be kept in mind—this is the Mazar of the descendant of Prophet Muhammad. In Islam, it is strictly prohibited to say bad things about someone else’s religion. But if someone says something bad about our Prophet, we naturally feel bad. Being Syeds, being the offspring of the Prophet, it is our duty [to speak up],” he said.

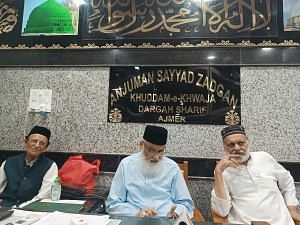

As secretary of the Anjuman Committee—the electoral, representative body of Khadims—his word carries weight.

Haji Salman Chishty, who has travelled extensively representing the Dargah in international forums, insists that the Khadims should steer clear of politics. While he denounced the Khadims who issued a bounty on Nupur Sharma, he’s more circumspect about Sarwar Chishti’s reminder of Muslims ruling India. “From childhood, we are taught to never ask the name, religion, language of whoever comes to Dargah Ajmer Sharif. If you have to ask them, ask them only one thing—how can we serve you? One of the titles of the Khadim community is Duago—one who prays for you,” he said.

Also read: Hindutva opponents must go beyond Muslims as invaders vs legal citizens categories

The world of Khadims

The Khadims claim to be descendant family members of Hazrat Khwaja Moinuddin Chishti, who arrived in Delhi in the 13th century, under the reign of Sultan Iltutmish. Khwaja eventually settled in Ajmer, where he strove to expand the influence of the Chishti Sufi order. It is said that the Prophet Muhammad appeared in Khwaja’s dream, asking him to he his ‘representative’ in India. Khadims are direct descendants of Syed Fakhruddin Gurdezi, the beloved cousin and devotee of Khwaja Moinuddin Chishti whom he accompanied on his journey to India from Iran.

Among the uninitiated, there remains much confusion as to who the Khadims are. Theirs is a byzantine, interlocked world of hundreds of men who assist in prayers, ferry visitors and VIPs, and speak as custodians. But in a world of viral videos and social media hot-takes, this loosely arranged structure of Dargah management riding solely on historical legacy has been caught off guard.

In this close-knit community, the lines dividing fact from myth are blurred. Thousands of people from Khadim families live in the dilapidated, multi-storeyed buildings that jostle for space in the labyrinthine gullies around the Dargah. They are the descendants of the seven families of Khadims whose job it was to look after the Dargah.

For 800 years, each generation has kept the keys of the Dargah. The keys change hands from one family to another every day at 3 pm.

Some Khadims are assigned specifically to VIPs—Haji Muqadas Moini is one of them. He has performed ziyarat for hundreds of important guests, and his phone rings non-stop with updates on other well-known people who are planning to pay respects at the Dargah. Two framed photos—one with a former minister of Rajasthan and another with a local Sufi saint—adorn the walls of his 10 by 10 drawing room.

Moini remembers each and every VIP visit, including personal guests of prime ministers and presidents. “I received Prime Minister Modi’s brothers when they came to the Dargah.”

He knows every custom and ritual, every hidden cranny in the gullies, and every crack in the buildings. His house stands apart from the rest with a board that announces his ‘very important’ status—‘VIP House—Haji Muqaddas Moini’.

Also read: Namaz isn’t an anti-Hindu act. Time for every Indian to defend Islam

Undertones of powerplay

In this peaceful setting where Khadims espouse equality, there are also subtle undertones of powerplay with families vying for prestige and spirituality.

“Whoever upholds and practises Khwaja Sahab’s teachings more sincerely will get the chance to represent his teachings. We are all equal, but not everyone is as spiritually awakened,” says Haji Salman Chishty. As the 26th generation ‘Gaddi Nashin,’ he often represents Ajmer Sharif Dargah in spiritual conferences around the world.

‘Gaddi Nashin’ is not an official post, but a spiritual one. More often than not, the eldest son takes the ‘title’. Some like Salman Chishty are often mistaken as the sole spiritual successors of the Dargah. It is a misconception that is a source of discontent back home.

Haji Syed Iqbal, another representative of the Khadim community, insists that international fame “doesn’t matter” in the larger scheme. “Ultimately they have to come and sit on the same kaleen (carpet) in front of Khwaja Gareeb Nawaz.”

The same rules apply to those Khadims who have chosen careers in other fields. “Our elder, Prof Syed Fazal ur Rehman Chishti Sahab taught chemistry at Aligarh Muslim University, and a gold medal is still given to students in his name. Syed Qamar Moini served at the United Nations. Many in our community hold government offices and academic positions,” says Salman Chishty.

Syed Danish Chishty, a young Khadim barely 30 years old, graduated from Ajmer Law College. Clad in a crisp blue kurta, he has just returned from completing an important Dargah ritual. He insists that no matter what profession a Khadim chooses, being a servant to the Dargah and doing Ziyarat will always remain a part of his life. “It’s given to us by birth,” he says.

Also read:

The younger generation

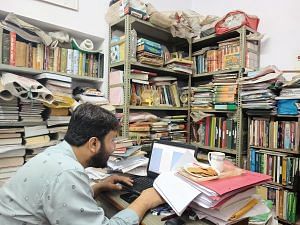

Danish and other young Khadim lawyers run a legal club, which looks at challenges of mismanagement of Dargah. They are planning a book exhibition featuring the writings of their forefathers on topics ranging from mathematics and science to spirituality and religion.

Their purpose is two-fold: to help the younger generation learn more about the legacy of their ancestors and inspire them to take up other professions. Many Khadims have built small libraries in their houses.

One such small, personal library is on the first floor of a five-storey building near the Dargah. The walls are covered by iron racks, their shelves laden with books in Urdu, Persian and English. There is no place on the table for even a cup of tea.

Here, another Khadim and ‘Gaddi Nashin’, Syed Aatif Kazmi, spends time researching and collecting documents related to the Ajmer Sharif Dargah and the Khadim community. He also shows the documents and Waqalatnama (power of attorney) of various kings— an old paper describing the offerings sent to Khadims for praying on their behalf. The papers have gold stamps from the kingdom of Dhaulpur, Dungarpur and Savai Madhopur, among others. These are some of his most prized possessions.

Unlike some of the other Khadims who take pride in their calling passed down over generations, Kazmi dismisses the importance given to heredity. “If you look at other saints also, the nearness to the Sufi and spiritual awakening is what gets priority when it comes to declaring a spiritual heir,” he said.

Also read: Politics over namaz inside historic Taj mosque likely to survive beyond 2019

Dargah Dewan versus Khadims

Heredity and duty form the foundation of their way of life, but here, too, there is conflict. Enter 72-year-old Syed Zainul Abedin, the Dewan (spiritual head) of the Dargah. He claims to be a direct descendant of the Sufi saint. But the Khadims reject this.

The conflict between Khadims and Dargah Dewan has its roots in the Mughal era, but played out in court hundreds of years later, in 2013. Cut to today, the Dewan must divide offerings equally with the Khadims. A board outside the main Dargah gate indicates which offerings by the devotees go to which party.

Abedin quotes the ‘farmaan’ (decree) of Shah Jahan to lay claim to being the descendant of Khwaja Moinuddin Chishty. The Khadims, on the other hand, quote the Akbarnama, the chronicle of the reign of Akbar written by Abu’l Fazl, to make a similar claim.

Abedin’s residence is just a stone’s throw away from the Dargah. But he is mostly bed-ridden and uses his wheelchair to perform select spiritual ceremonies, such as ‘Ghusal’ (bathing of the holy shrine). He claims to be the sole ‘Sajjadanashin’ (hereditary administrator or spiritual successor) of the Dargah.

In 2018, appointment of Abedin’s son Syed Naseeruddin as the successor was opposed by the Khadim community on the grounds that there cannot be two Sajjadanashins. Abedin responded by saying he did not anoint his son as Sajjadanashin, but only as his successor. That said, Naseeruddin still performs some ceremonies during the Urs festival, which are carried out in the presence of Khadims.

Another argument, that the Sajjadanashin gives, is that Khadims are the descendant converts originally belonging to the Bhil tribe, as mentioned in Islamic scholar P.M. Currie’s book, The Shrine and Cult of Muʻīn Al-Dīn Chishtī of Ajmer. Khadims oppose this and allege Currie’s book is based on ‘secondary sources.’

The Dargah Dewan and his successor have been often seen holding forth on political issues, giving their support to many government’s decisions like repeal of Article 370 or triple talaq. He has also been vocal about banning radical organisations. Both father and son told thePrint that it pains them to see the Dargah being associated with extremist elements.

Also read: Muslims must give up azaan by loudspeakers. Even Prophet would have rejected it

How Khadims look at the controversy

The videos calling for revenge have caused much unease among the young Khadim community, especially those who promote peace unequivocally—Sajjadanashin and Khadims alike.

“Whoever drifts away from the teachings of Khwaja Gareeb Nawaz, is acting on their ego and ambition. They do not represent the teachings of Khwaja Gareeb Nawaz or the Chishty order. We denounce anyone who raises such slogans and divide the society,” says Haji Salman Chishty.

The langar at the Dargah, even today, is made without onion and garlic. The roses and flowers that are offered are brought from Pushkar, the land of Brahma. Ajmer is a place where Khwaja Gareeb Hotel and Shri Krishna Sweets stand next to each other, where a Muslim buys sweets from Shri Gajanand sweets and a Hindu gets ‘Loban dhoop’ (incense) from a Syed’s shop.

In his last sermon, Khwaja Moinuddin Chishti urged his followers to avoid politics and courts. “Never go to the courts of kings and rulers, but never refuse to bless and help the needy and the poor, the widow and the orphan, if they come to your door.”

But in this ‘new age’ where viral videos set the trend for overarching narratives, and where tweets drive storylines, the Khadims are drawn into the debate. Silence isn’t always the right answer.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)