New Delhi: Oceans have helped humanity avoid the worst of climate change so far, but paid a heavy price for it.

Climate calculations by NASA and the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) suggest that the Earth’s temperatures have defied the meteoric rise in CO2 levels in recent years to stay lower than they should have been — because oceans, which cover 71 per cent of the planet’s surface, soaked up most of the excess heat.

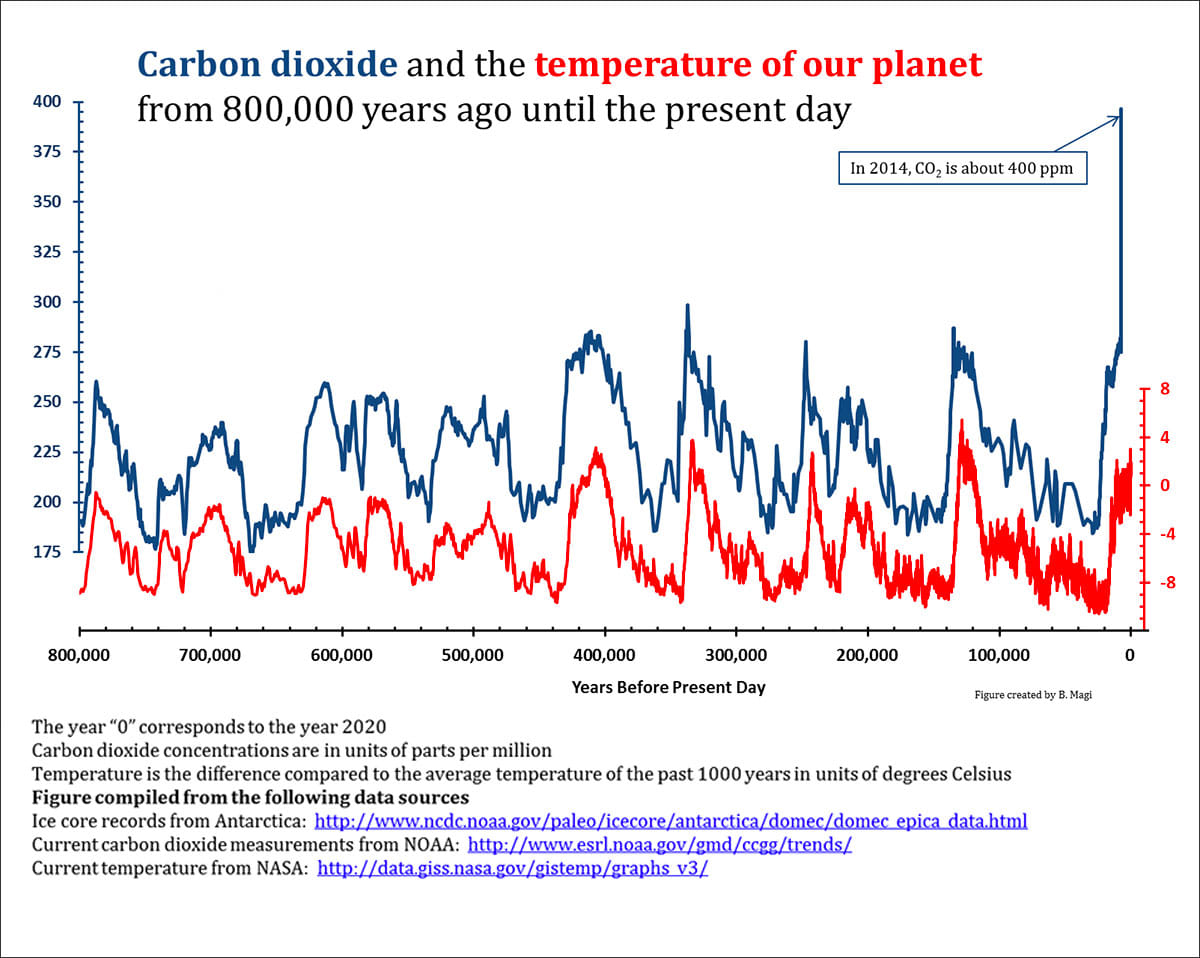

This phenomenon was best depicted in a graph (see below) plotted by American atmospheric science professor Brian Magi.

The graph shows in blue the CO2 concentration in the atmosphere, in parts per million, and the contemporary climate position, represented by polar temperature in degrees Celsius and depicted in red, for the past 8 lakh years.

The first thing that is immediately noticeable is the close relationship between atmospheric CO2 concentration and temperature. The peaks and valleys of the two curves align very closely with each other.

That pattern, however, changes towards the end of the graph, which represents the second decade of the 21st century — it was around 2013 that CO2 in the atmosphere breached 400 ppm for the first time after millions of years.

The growth is sharper than at any point in the graph too, an obvious depiction of growing industrialisation around the world.

As shown in the graph, in the preceding 8,00,000 years, CO2 concentration in the atmosphere fluctuated between just 180 ppm and 300 ppm.

The last time atmospheric CO2 levels were close to 400 ppm was 3 to 5 million years ago, during what is known as the Pliocene Epoch, when the Earth was a very different planet. The North Pole was largely ice-free at the time, the global average temperature was 2-3 degrees Celsius higher than today, and the sea level 30 to 90 feet higher.

Also Read: Adapting to climate change now will come at a heavy cost

Some breathing space

The primary cause for climate inertia is the ability of oceans to soak up excess heat — and, because oceans are so expansive and deep, it takes a long time and a lot of energy to exhaust their capacity.

“Ocean water mixes way down [thousands of metres], because the wind stirs the ocean. So, you must warm up all that water,” James Hansen, director of the climate science, awareness and solutions programme at the Earth Institute, Columbia University, and former NASA scientist, told ThePrint in an email.

“It takes a long time,” he added. “After 100 years, it has only warmed about 60 per cent of the way to the eventual response.”

In other words, our oceans are acting as enormous heat sinks that are gobbling up all the excess energy due to the increasing concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere — energy that, otherwise, would have been absorbed by the atmosphere and land.

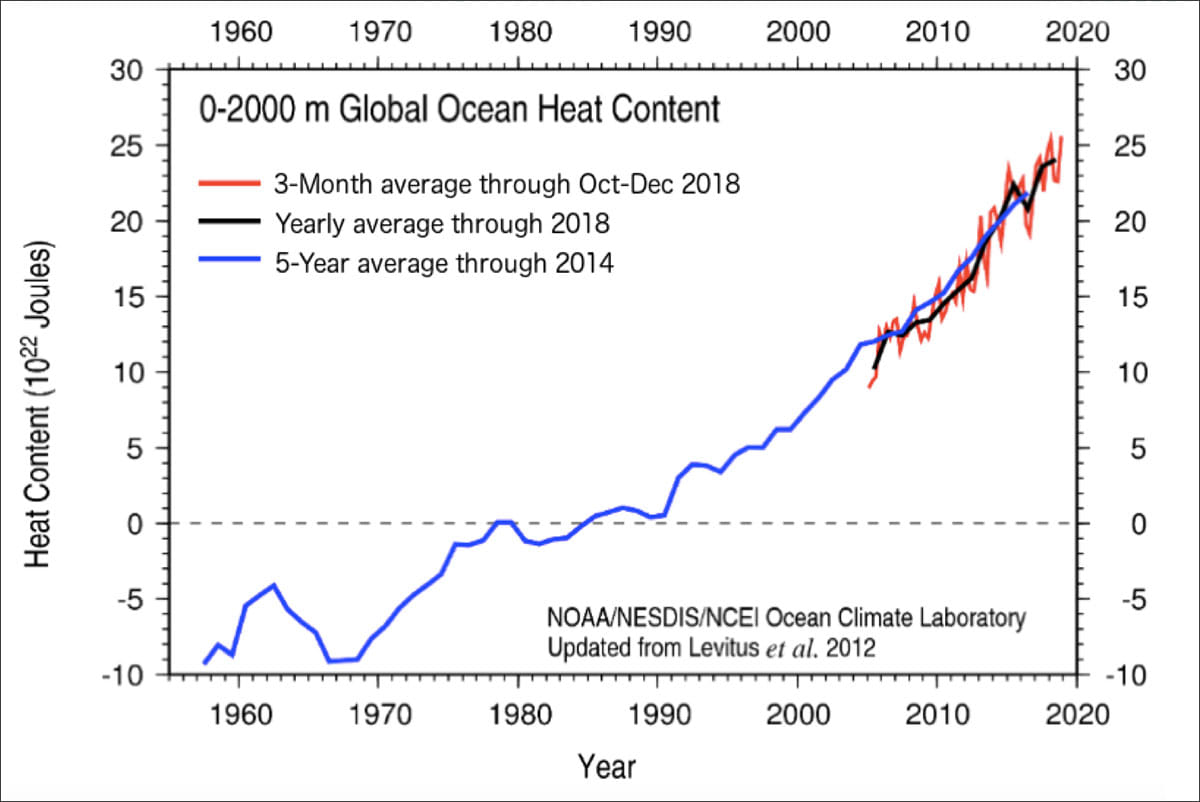

The fact is further established if we look at the change in ocean heat content over recent years. The graph below shows that there has been a relentless increase in the amount of heat stored in the ocean since the late 1960s, which has been accompanied by an increase in ocean temperatures.

However, while it has given humans and other land animals some breathing space, the rise in ocean temperatures has huge implications for aquatic species.

Deep-sea corals and the marine species they sustain have been hit hard by rising ocean temperatures. For example, about 30 per cent of the 3,863 corals on the Great Barrier Reef, the world’s largest coral reef system, died within a nine-month period during the global ocean heatwave in 2016.

Counting on technology

The 2015 Paris agreement is currently the world’s blueprint for staving off some of the worst expected consequences of global warming. The agreement urges immediate action to restrict temperature increase to 2°C above pre-industrial levels, while also setting out the more ambitious aim of restricting warming to 1.5°C.

Scientists estimate that the average global temperature has already risen 1°C over pre-industrial temperatures, which shrinks humanity’s room to manoeuvre.

Hansen suggested that while the longer window afforded by oceans is important, it may threaten to leave humans complacent about the crisis they face.

“The delayed response is our friend, as well as our worst enemy. It means that we have time to reduce CO2 below 350 ppm [the safe limit] before the equilibrium response is attained,” said Hansen. “The equilibrium response of 2 degrees Celsius will never be reached if we are smart,” he added.

While reducing carbon emissions is the logical solution to arrest any further growth in atmospheric concentration, it is also important to remove CO2 from the atmosphere to stay below the safe limit — apart from natural carbon sinks like forests, scientists are exploring technological solutions to keep carbon levels in check.

While still in their early stages, direct air carbon capture and storage technologies seem like promising solutions, but much research and development is required to make this an economically feasible, scalable option.

The author is a freelancer and has a keen interest in the science of climate change and the environment.

Also Read: Climate change threatens cultivation of Indian banana, global warming likely to hit output