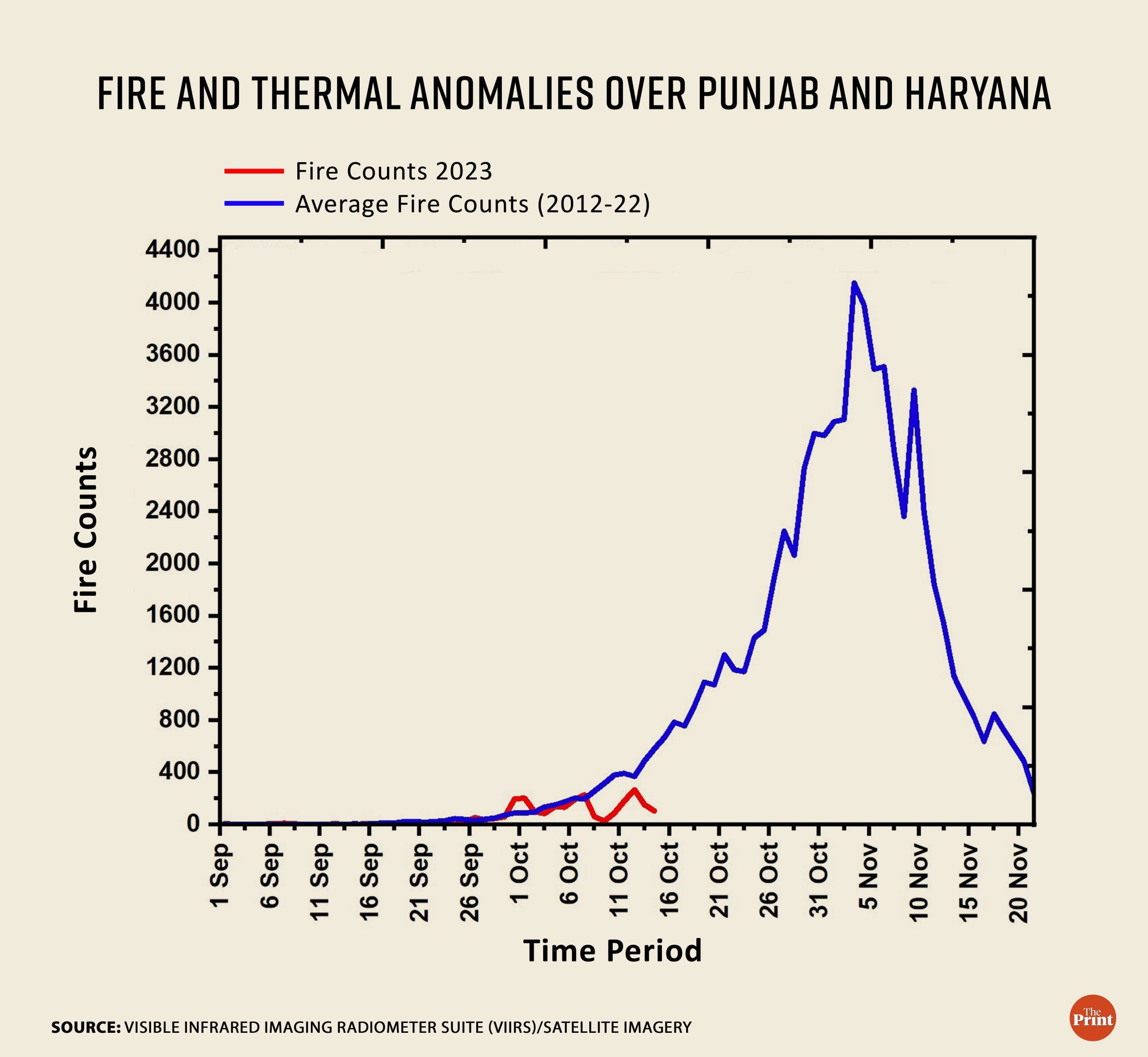

New Delhi: As Delhi’s air quality remains poor, satellite data shows that the number of stubble burning incidents reported from northern India this year are lower than average fire counts over the last decade, a top scientist from Chandigarh’s Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research (PGIMER) told ThePrint.

Ravindra Khaiwal, a professor at PGIMER’s Department of Community Medicine & School of Public Health said several on-ground initiatives to curb stubble burning could have led to a 10-15 percent drop in the stubble burning incidents in northern India.

According to Khaiwal, as on 15 October, the count of farm fires in Punjab and Haryana, two states known for stubble burning, was 106 — 85 in Haryana and 21 in Punjab.

Further, data from the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) shows that as of 16 October, the number of farm fires detected across India using satellite imagery stood at 338, as compared to 632 in 2022, 1,537 in 2021, and 1,172 in 2020.

Air pollution remains a major problem in cities across India — but especially in Delhi-NCR.

According to a 2018 study by The Energy and Resources Institute (TERI) and the Automotive Research Association of India (ARAI), the major sources of pollution in Delhi in the summer include dust and construction activities (38-42 percent), transport (15-17 percent) and industry (22 percent).

But air pollution is especially bad in the winter, a time when farmers in Punjab and Haryana begin to clear out the paddy residue on their farmlands by setting it on fire. The particulate matter from these fires travels down the entire Gangetic plain, enveloping vast swathes of northern India in smoke, according to the study.

As a result, cities in the NCR region including Delhi, Noida, and Gurugram — already choked with pollution from vehicles and industries — bear the brunt, as their meteorological conditions prevent the smoke from dissipating.

As winter sets in, the cold makes it harder for the particulate matter to rise up — leaving people exposed to the toxic smog. In order to help stubble burning, the Punjab government has subsidised ‘Happy Seeders’ — a no-till planter towed behind a tractor to sow seeds. It has also conducted awareness drives and set up pilot projects to advocate the use paddy straw for various end-user applications like biofuels.

Also Read: Burning of twigs, dry leaves for warmth & vehicles biggest pollutants in Delhi, shows study

Why Delhi’s air quality is ‘poor’

According to the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB), the air quality index over Delhi was 207 Tuesday.

On India’s air quality index (AQI), a value in the 0-50 range is considered “good”, 51-100 is “satisfactory”, 101-200 is “moderate”, 201-300 is “poor”, 301-400 is “very poor”, and 401-450 is “severe”, while a value above 450 is considered “severe+”.

According to the India Meteorological Department’s (IMD) air quality forecast, the predominant surface winds — which would help dissipate accumulating pollutants — should have speeds of 10 kmph. But according to the Met Department, winds from the east/north directions in Delhi will have a speed of 4-8 kmph Wednesday.

Moreover, the predominant surface wind is likely to come from northwest directions at 8-16 kmph, the report, published Tuesday, went on to say. It also stated that a parameter known as ‘Ventilation Index’ — an estimate of how well the atmosphere disperses smoke on any given day — is going will be below 3,500 sq.m/second Wednesday.

A Ventilation Index lower than 6000 sq.m/second with an average wind speed under 10 kmph is unfavourable for dispersing pollutants. This implies that Delhi AQI is likely to remain in the ‘poor category’.

But IMD also forecasts a slight improvement in air quality after 18 October as wind speeds pick up, with the AQI predicted to improve to moderate.

According to Khaiwal, among meteorological conditions that affect Delhi’s air quality include “wind conditions, temperature, humidity, and a parameter known as mixing height, which influences how the pollutants from sources within the city dissipate”.

Mixing height describes the vertical height at which pollutants are able to disperse. A higher mixing height would allow suspended particles to rise with warm air and dissipate.

(Edited by Uttara Ramaswamy)

Also Read: You thought only winter meant bad air in Delhi? Govt data tells a different, worrying story