Bengaluru: All nine zones in Bengaluru have witnessed a steady and alarming fall in groundwater levels in the past decade, according to the Karnataka’s Groundwater Directorate, indicating the growing concern of overexploitation in India’s IT capital which experts say will have irreparable consequences.

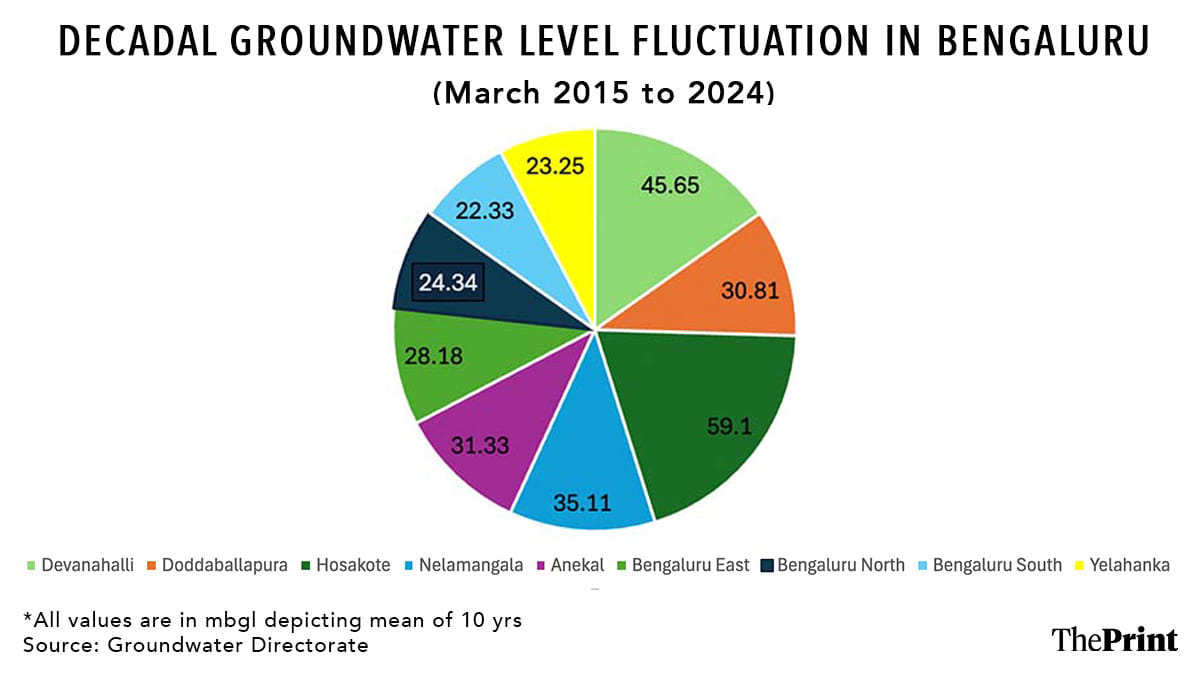

The nine zones that fall under this category are Devanahalli, Doddaballapura, Hosakote, Nelamangala (under Bengaluru Rural), Anekal, Bengaluru East, Bengaluru North, Bengaluru South, Yelahanka (under Bengaluru Urban).

The assessment period for taluka-wise decadal groundwater level fluctuation was from March 2015 to March 2024. While the Groundwater Directorate provided the March 2025 average findings as well, ThePrint considered the 2015-2024 period for the report.

Most zones in Bengaluru Urban, the data shows, are seeing a continuous depletion of groundwater levels with East showing fluctuation from 17.86 metres below ground level (mbgl) in March 2015 to 37.76 mbgl in March 2024.

Other zones like Anekal, South, Yelahanka too have seen depletions ranging from 4.20 mbgl to nearly 12 mbgl in the 10-year period, according to the data from Groundwater Directorate.

The decadal study shows that Bengaluru Rural faced the most severe groundwater depletion, with an average depth of 45.65 mbgl—the deepest among all taluks in Bengaluru district. This is followed by Bengaluru Urban at 31.33 mbgl, and Bengaluru East at 28.18 mbgl, both reflecting significant stress likely due to rapid urbanisation and over-extraction.

Average depth of groundwater in Bengaluru North and South is 24.34 mbgl and 22.33 mbgl, suggesting relatively better groundwater availability.

The pie chart given below shows that Bengaluru Rural alone accounts for the largest share of groundwater level fluctuation, raising red flags for policymakers and urban planners. The data points to an urgent need for stricter regulation of borewell drilling, better rainwater harvesting infrastructure, and long-term groundwater recharge strategies across the district.

Zones in Bengaluru’s outer periphery fare no better, with Devanahalli, one of the fastest growing regions near the city’s international airport, has seen the sharpest fall from 32.2 mbgl in March 2015 to 73.74 mbgl in March 2024.

However, there has been some recovery with the latest figures up to 60 mbgl in Bengaluru Rural sone, according to government data.

While this may be true of all urban centres across India, the problem in Karnataka is far more challenging than most others. One of the reasons is inequitable development which has centred around Bengaluru, forcing mass migration from all parts of the state as well as the country.

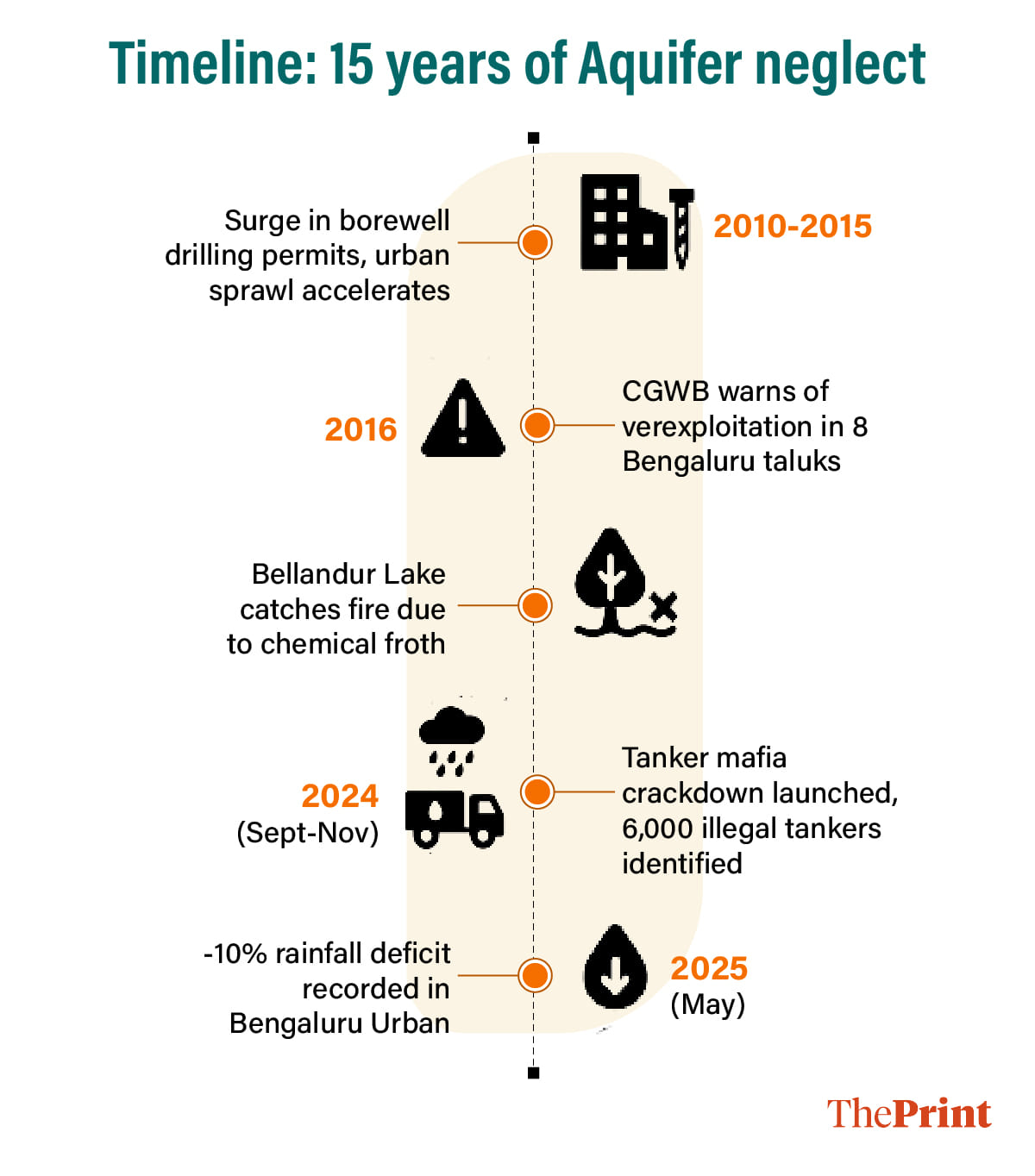

“This didn’t happen overnight. We’ve been drawing from the ground without ever thinking of putting anything back. People think a few heavy showers means that groundwater is recovering. But when the land is hardened by concrete, rain just runs off and does not seep in,” Dr. H.P. Jayaprakash, senior scientist at Central Ground Water Board (CGWB), told ThePrint.

While the CGWB functions independently under the Ministry of Jal Shakti, the Groundwater Directorate is typically a state-level department focusing on local implementation and management of water resources.

Different surveys, same findings

In its ground water year book of Karnataka 2023-24, the CGWB tracked groundwater across 1,334 dug wells and 763 piezometers—geotechnical sensors that are used to measure pore water pressure—for presenting the state of underground water.

The findings show that 62 percent of shallow wells reported a decline in Bengaluru’s water levels, while the remaining saw marginal rises. The situation is no better in other parts of Karnataka as over 55 percent of shallow wells recorded a decline between August 2024 and November 2024.

Similarly, the CGWB’s 2024 Karnataka bulletin shows depth fluctuations ranging from a 14-metre drop to minor 2-metre increases in groundwater level in Bengaluru.

A significant chunk of Bengaluru depends on borewells and water tankers as Cauvery water piped connections remain low–if not non-existent–in most parts in the outer periphery of the city. As official borewells dry up, the city’s reliance on water tankers—many illegal—has surged. These tankers often extract water from unregulated borewells in rural areas, with little oversight.

The acute water shortage was seen last year with the Bengaluru Water Supply and Sewerage Board (BWSSB) imposing fines for wastage of water as well as high-end housing societies levying strict rules for better usage of the scarce resource.

For causes of groundwater level depletion in Bengaluru, the deeper the city digs, the longer it takes to bounce back. While some deep aquifers (100-plus metres) showed improvements, the CGWB cautions that these reserves are slow to replenish. Once exhausted, they may be lost for decades.

“It’s not just about depth. It’s about sustainability. These tankers supply water from private borewells, which the government cannot monitor effectively. Once the deeper aquifers are gone, they won’t come back in our lifetime,” Suchetana Biswas, associate scientist at CGWB, Bengaluru, told ThePrint.

While policymakers claim rainfall has been “normal,” hydrologists say otherwise. The crisis, they argue, stems not just from climate variability, but years of unchecked borewell drilling, urban concretization, drying up of lakes and policy inertia.

Another major cause of groundwater depletion is the drying up of lakes in Bengaluru. In the 1970s, Bengaluru had 68 percent green cover. Today, that figure has shrunk to just 3–4 percent, with 86 percent of the city covered in impervious surfaces.

Lakes have been encroached upon, and rivers like the Vrishabhavathi now function more like drains than water bodies. Bellandur Lake, once a symbol of Bengaluru’s water culture, now froths with toxic chemicals and occasionally catches fire—dramatic evidence of the ecological collapse.

(Edited by Tony Rai)

Also Read: Bengaluru under water, Siddaramaiah govt gears up for grand 2-yr anniversary