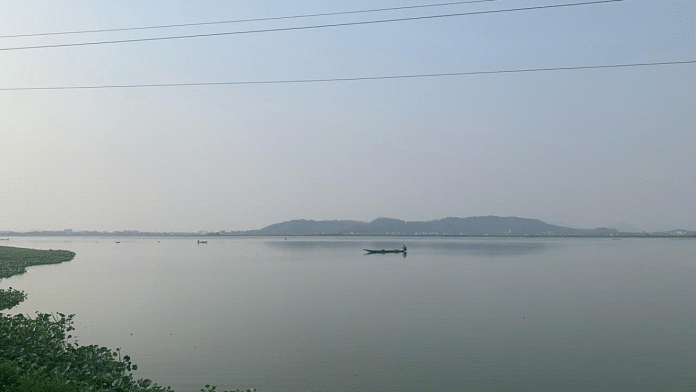

Guwahati: As Assam’s Himanta Biswa Sarma government tries to push ahead with its eco-tourism plans for Deepor Beel — a permanent freshwater lake near Guwahati and the state’s only protected Ramsar site — residents and conservationists say they are not averse to development but want to be assured that it won’t come at the cost of the ecology.

Speaking during the budget session of the state assembly earlier this month, the state’s tourism minister, Jayanta Mallabaruah, blamed the state’s forest department for impeding its plans to promote eco-tourism at Deepor Beel.

“As on date, we have a fund of Rs 14 crore in the tourism department lying unutilised for Deepor Beel. The court has issued directions to pursue projects like building of a cycle track around the beel (lake) but the forest department has been obstructing the plans,” the minister said in his response to Asom Gana Parishad (AGP) MLA Ramendra Narayan Kalita.

The speech came two months after the state government unveiled its “beautification plan” for the lake, including a cycling track, boating facilities, and other tourist amenities at the site.

While maintaining the ecological balance at Deepor Beel, we are working on a beautification plan that involves a new road encircling the lake, a cycling track, boating facilities & offering visitors a well-rounded experiencehttps://t.co/WvgJHTmeSb

— Pijush Hazarika (@Pijush_hazarika) December 12, 2023

It also came at a time when a survey conducted at the beel (lake) highlighted some concerning statistics. In its survey, released during the annual four-day Winter Birding Festival in January, 7WEAVES, a Guwahati-based environmental research group, said there had been a decline of 16,000 migratory birds at the lake between December and January this year compared to the last.

Residents and activists ThePrint spoke to remain skeptical of the government’s eco-tourism plans, with many saying that while development was necessary, it should not upset the wetland’s ecology.

How can one talk of development without conducting a feasibility study to understand the environmental impact of these plans, Pramod Kalita, an activist, asked.

“If a cycling track is built around the peripheral area, it can be destructive,” he told ThePrint. “Most of the civilian population is associated with Deepor Beel for livelihood. If the beel dies out, it will directly impact the fisherfolk.”

A senior official at the state’s forest department declined to comment on the issue, telling ThePrint that “it (the issue) is pending in the cabinet”.

However, Padmapani Bora, managing director of the Assam Tourism Development Corporation, said that the department was keen on having eco-tourism activities at Deepor Beel. But he also told ThePrint that there should be a “balance between development and conservation”.

“Deepor Beel is one of the attractive tourist sites near Guwahati. Those landing in Guwahati can have a glimpse of the beel on their way to and from the airport. (But) tourism infrastructure and activities need to be carried out without compromising wetland protocols as it’s a Ramsar site and part of the beel is also an animal corridor,” Bora said, adding that for this, it was relying on the state’s forest department for guidance.

Also Read: In Assam, trains prey on elephants. But Haati Mitras, AI have been defeating them for 4 yrs

Legal status of the beel — from wetland to wildlife sanctuary

Coming under Assam’s Kamrup district and spanning around 900 hectares, Deepor Beel (literally translated as the lake of elephants) is a wetland that’s home to several species of birds in and around the sanctuary.

It’s a designated site of importance under the Ramsar Convention — an international treaty for the conservation of wetlands.

Some of the more commonly seen water birds here are the bar-headed goose, the lesser whistling duck, the Indian pond heron (konamusori in Assamese), the greater adjutant (known locally as hargila), and the grey-headed swamphen (kam sorai).

A core area of 4.1 sq km in this wetland is designated as the Deepor Beel Wildlife Sanctuary — maintained by the wildlife division of the forest department. The area beyond is maintained by the district administration and the Guwahati Metropolitan Development Authority.

Deepor Beel is also a notified elephant corridor.

There are at least eight villages around the lake. Their occupants, most of them from the indigenous Karbi tribe, are mainly engaged in fishing and cattle grazing, with some running small businesses.

It was in 2002 that the lake was declared a Ramsar site. Typically, this recognition, among other things, acts as an international obligation to look after these sites. Once made part of the Ramsar list, the sites also garner attention from civil society groups, conservationists, and academics.

In 2009, the state government under the then chief minister, Tarun Gogoi, issued a notification declaring 4.1 sq. km of the water body a “wildlife sanctuary” under the Wild Life (Protection) Act, 1972.

Until this notification, the beel was being maintained by the state’s fisheries department.

The state government’s move was met with protests, with the local fisherfolk claiming it would mean the loss of traditional livelihood for those dependent on the beel.

In 2017, a single bench of the Gauhati HC quashed the 2009 notification. However, this move was reversed in March 2023, when a division bench upheld the notification. This ruling hasn’t been appealed against yet.

“Apart from being a staging site for the migratory birds, Deepor Beel is the only major stormwater storage basin for the city of Guwahati. Therefore, preservation and protection of Deepor Beel is a measure in the larger public interest for the residents of the Guwahati city,” the court’s March 2023 ruling said.

Despite the order being passed last year, it found no mention in Tourism Minister Mallabaruah’s response to the House this February. However, he did refer to the 2017 ruling.

“The question remains whether Deepor Beel is a wildlife sanctuary or not,” the minister continued, pointing out that there was no cabinet nod to the 2009 gazette notification.

“The forest department says that a wildlife sanctuary, once declared, cannot be denotified unless the Supreme Court rules so. Here, there’s no question of denotification. The high court had cancelled the final notification on the sanctuary status of the beel.”

‘Not averse to development’

As the state government continues to push for eco-tourism activities in the area, environmentalists are worried about the ecological cost of these plans.

Already, like several Ramsar sites in India, the threat of urbanisation looms large over the ecologically sensitive zone, which is fighting a war on multiple fronts — unregulated tourism, shrinking water bodies, pollution, and haphazard and unplanned urbanisation.

Until 2021, the area next to the waterland also had a 31.1-hectare landfill site, where untreated detritus from Guwahati was dumped for 15 years. Although it’s now officially been moved elsewhere, its effects can still be felt — legacy waste continues to degrade this eco-sensitive area, with illegal dumping still occurring at the Boragaon dumping site near Deepor Beel, according to villagers.

According to activists, despite being declared a Ramsar site in 2002, there has been no official demarcation of the lake, leaving it vulnerable. “Development is essential, (but it should be done) without destroying the wetland, and (it) shouldn’t be done in haste,” Kalita, quoted earlier, said.

The government should prioritise conservation over “haphazard development,” Golak Das, a 53-year-old activist who lives in the Keoptara, a small fishing village on the periphery of the beel, told ThePrint.

Das is the secretary of the Deepor Beel Paraspara Samabay Samiti, a civil society group that’s been fighting for local fishermen’s rights. The samiti was one of the organisations that filed the petition challenging the 2009 notification, arguing that in giving wildlife sanctuary status to Deepor Beel, the state government had disregarded the traditional fishing rights of those living around the Ramsar site.

Like Kalita, Das, too, has reservations about the government’s plan for a cycle track around the lake and calls for demarcation of the Ramsar site.

“We don’t know how the minister hopes to bring about development, but one thing is clear — the proposed cycle track cannot be a good idea without studying its implications,” Das said. “First, the demarcation of the entire Ramsar site — and not just the 4.1 sq km area designated as Deepor Beel wildlife sanctuary — should be done.”

Concrete structures in the area — built with government permission — have led to the water body shrinking, he said. “More structures would reduce it to a mere fishery,” he added.

Eco-tourism activities in bird sanctuary

Despite these protests, some eco-tourism activities have already been conducted near the wetlands. Many of the places around the beel have now turned into picnic spots.

Last November, the Assam government, in collaboration with the Army, organised the Rising Sun Water Festival — a three-day water sports festival — near the wetlands. The event sparked a row, with both locals and environmentalists claiming that water levels in the lake were artificially raised, which hindered the migration of winter birds and affected the movement of elephants that descend from the neighboring Rani Garbhanga hills to the beel to drink water.

All of this has gravely reduced biodiversity in the area, activists have told ThePrint. It’s in this light that the 7WEAVES research group survey — which found that a total of 11,271 water birds of 155 species were spotted in the area between December and January, compared to 28,331 birds of 161 species in 2022 — becomes important.

“Rather than organising festivals, the priority should be removing dumping grounds near the wetlands and sewage water treatment. There’s no need to spend crores of rupees on Deepor Beel if these are done,” Kalita said.

On its part, Assam Tourism Development Corporation aims for a “middle path”. “Whatever development happens, the tourism department will abide by the rules and regulations under the Environment Protection Act for the conservation of wetlands,” he told ThePrint.

Residents want to make it clear that they aren’t against development in the area. Indeed, they hope that, with eco-tourism plans in the pipeline, authorities would once again allow the use of traditional fishing boats, banned in the core area since 2014.

But they also assert that the government has so far shown no interest in addressing their concerns, and that although they have sought meetings, these have yet to happen. “The dumping ground (Boragaon) was part of the water body where we did fishing once. If no steps are taken to protect the beel from further destruction, we will be forced to stage protests,” Das said.

(Edited by Uttara Ramaswamy)

Also Read: ‘Belur Makhna’ leads Kerala forest dept on wild elephant chase as human-animal conflict intensifies