New Delhi: Petrol prices crossed Rs 100 per litre in several Indian cities over the past few weeks, feeding into inflation and putting pressure on household budgets.

While the increase in prices of petrol and diesel can be explained by rising international fuel prices to some extent, the high incidence of taxes on these products also has an important role to play. The two-month freeze in fuel price hikes in the election months of March and April is another factor.

The Narendra Modi government has so far resisted cutting taxes on petroleum products, despite the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC), headed by the Reserve Bank of India governor, pushing the Centre and states to cut these taxes to ease inflation pressures on the economy.

ThePrint explains why fuel prices surged in May.

Tax effect on oil prices

India meets its domestic oil demand mainly through imports. While international crude prices have risen sharply in the last six months, a major reason for the high selling price of petrol is the high levy of local taxes.

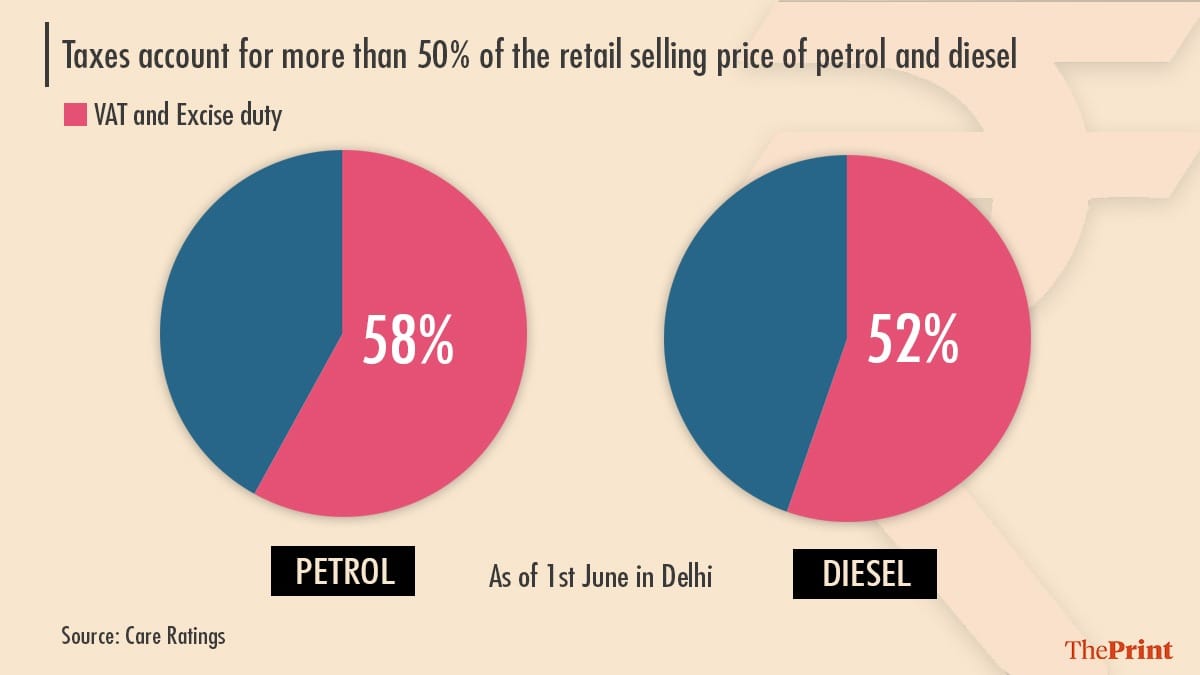

The Union government levies excise duty and cess on fuel, and states levy a value added tax (VAT). Taxes together constitute 58 per cent of the retail selling price of petrol and around 52 per cent of the retail selling price of diesel at present. This means that if the price of petrol is Rs 100 per litre, taxes levied by the Modi government and state governments together account for Rs 58.

Of this, the Union government’s excise duty is around Rs 32-33 and the remaining is VAT that is levied by the states.

The last time fuel prices in India had surged was between 2010-11 and 2013-14, during the tenure of the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government. But at the time, the surge was mainly on account of a sharp rise in international crude prices that had touched all-time highs.

The average price of the Indian basket had exceeded $100 during those years. However, even then, the retail price of petrol in Indian cities had remained under Rs 90 per litre due to the low level of prevalent taxes. Excise duty in that period was as low as Rs 10 on petrol.

When the international crude prices began falling beginning 2014-15, the Modi government started increasing excise duties beginning November 2014.

This meant that the benefits of the fall in international fuel prices were not passed on to customers.

Also read: RBI allows takeover of PMC bank by Centrum Financial Services to set up small finance bank

Why governments are reluctant to cut taxes on fuel

The Modi government and the states have been reluctant to slash rates even amid rising international prices as these taxes are a major source of revenue. Over the last few months, both sides have passed the buck over fuel tax reduction and resisted making the first move to cut taxes.

It’s not difficult to see why.

The Modi government collected Rs 3.89 lakh crore in excise duty collections in 2020-21, a 62 per cent growth from Rs 2.39 lakh crore collected in 2019-20, of which a majority is estimated to be from taxes and cess on petrol.

This increase in tax collections came despite the fact that petroleum consumption contracted 9 per cent in 2020-21 due to curbs on movement on account of the Covid-19 pandemic. It can be attributed to the sharp hike in taxes levied on petroleum products in May 2020.

At the time, the Modi government had increased petrol prices by Rs 10 and diesel by Rs 13. This sharp increase came just two months after the government’s decision to hike excise on petrol and diesel by Rs 3.

Typically, for every Re 1 of excise hike on petrol and diesel, the gain to the exchequer is around Rs 13,000-14,000 crore. However, with the Covid-related consumption slump, the gains may be a bit lower than this.

It’s the same story for the states. Most states hiked VAT on petrol and diesel in 2020-21 to shore up revenues at a time the slump in economic activity adversely impacted other sources of revenue.

VAT levied on petroleum and alcohol account for 25-30 per cent of the states’ tax revenues, an important reason states have been opposed to inclusion of petroleum products under the goods and services tax.

According to data with the petroleum ministry, states collected more than Rs 2 lakh crore in 2019-20 and Rs 1.35 lakh crore in April-December 2020-21 from VAT on petroleum products.

Administered pricing mechanism dismantled, but govt controls remain

Beginning June 2017, India did away with the administered pricing mechanism for petroleum and diesel. This meant that petroleum companies were free to change fuel rates daily in line with international oil price movements. Petroleum companies can also revise these prices daily during events like elections.

Yet, fuel companies chose to not increase rates even once in the months of March and April, coinciding with assembly elections in four states and one Union territory.

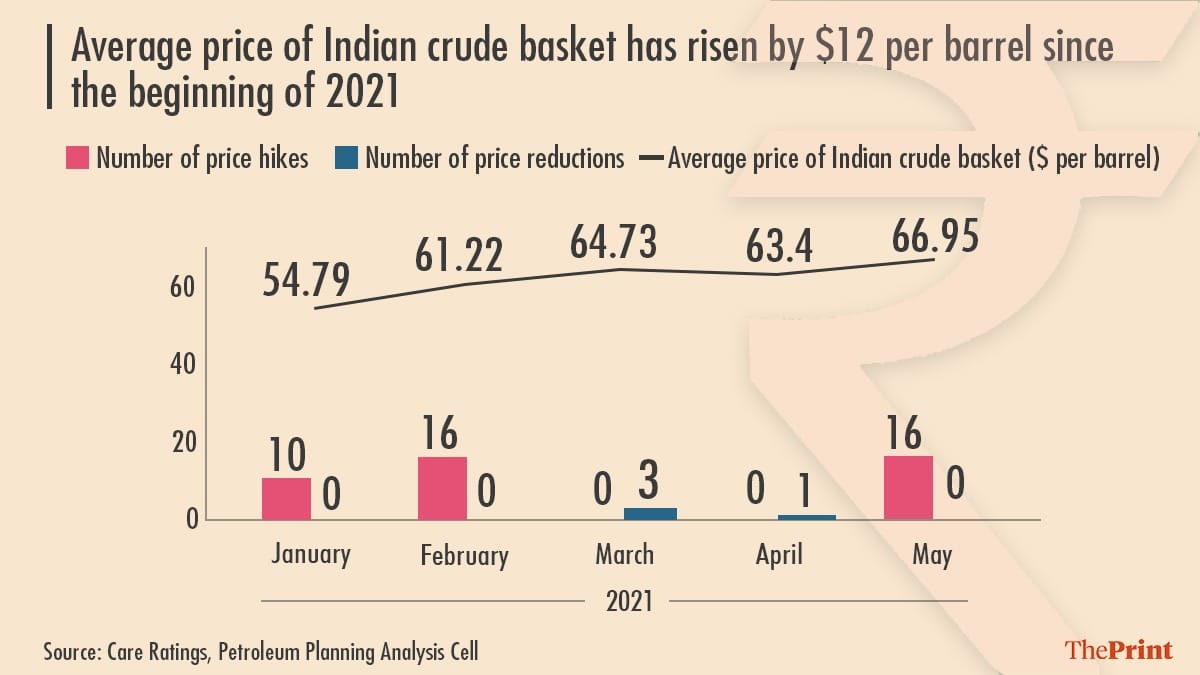

The fuel companies actually cut rates thrice in March and once in April as against 16 price hikes in February, according to data collated by Care Ratings. The average price of India’s crude basket had increased by $3.5 in March from February before falling by $1.3 in April.

In May, oil companies raised prices 16 times even though crude prices went up only $3.5 compared to April, reflecting their attempt to make up for the two lost months when the domestic prices didn’t accurately reflect the international prices.

Lack of increase in fuel prices during elections is not surprising in a market like India where state owned oil marketing firms have over a 90 per cent market share.

Also read: Growth, not inflation, has become RBI’s priority after second wave of Covid

Inflation impact

The rise in fuel prices has added further pressure to India’s inflation, which crossed 6 per cent in May.

Earlier this month, the MPC had also flagged the impact of the high fuel prices on overall input prices. It had urged the central government and the state governments to cut taxes on petrol and diesel in a coordinated manner.

India’s fuel inflation was at 11.6 per cent in May, as against 7.9 per cent in April and 4.5 per cent in March.

There are also concerns that an increase in fuel prices may have an adverse impact on discretionary expenditure as households cut the latter out to accommodate higher fuel prices.

(Edited by Amit Upadhyaya)

Also read: Financial instability looming over India’s banking sector: RBI’s ex-dy governor Rakesh Mohan