New Delhi: Indicator after indicator has brought India bad news for its economy. Auto sales, one of the strongest indicators for economic health, are down by approximately 25 per cent. Tractor sales, another top indicator in an agrarian economy like India’s, have fallen 14 per cent. Another critical statistic, unemployment data, shows job creation at a four-decade low.

But it’s not that dark everywhere. Indians are watching films and purchasing food items and beverages (F&B) at movie halls, purchasing streaming subscriptions for movies and music, and buying milk and milk products in abundance. They are also switching their smartphones for newer models at a healthy clip.

Dairy major Amul has registered a growth of 26 per cent in the last six months, with the curd segment up 40 per cent. Netflix, far from the most popular streaming portal in India, reportedly grew 700 per cent in 2018-19. Footfall at cinema halls run by PVR, one of India’s leading multiplex chains, is up 25 per cent since the last financial year, according to insiders, and F&B revenue by 38 per cent.

The chain registered one of its brightest revenue seasons last quarter, with earnings of Rs 1,000 crore.

And even if millennials are precipitating the automobile slowdown by not buying cars and opting for ride-hailing apps, as Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman claimed earlier this year, it is this age group that is driving the growth in booming sectors, say experts.

Also read: GDP growth could drop below 5% in Q2 as factory output sees biggest contraction since 2011

Millennials and the age of the internet

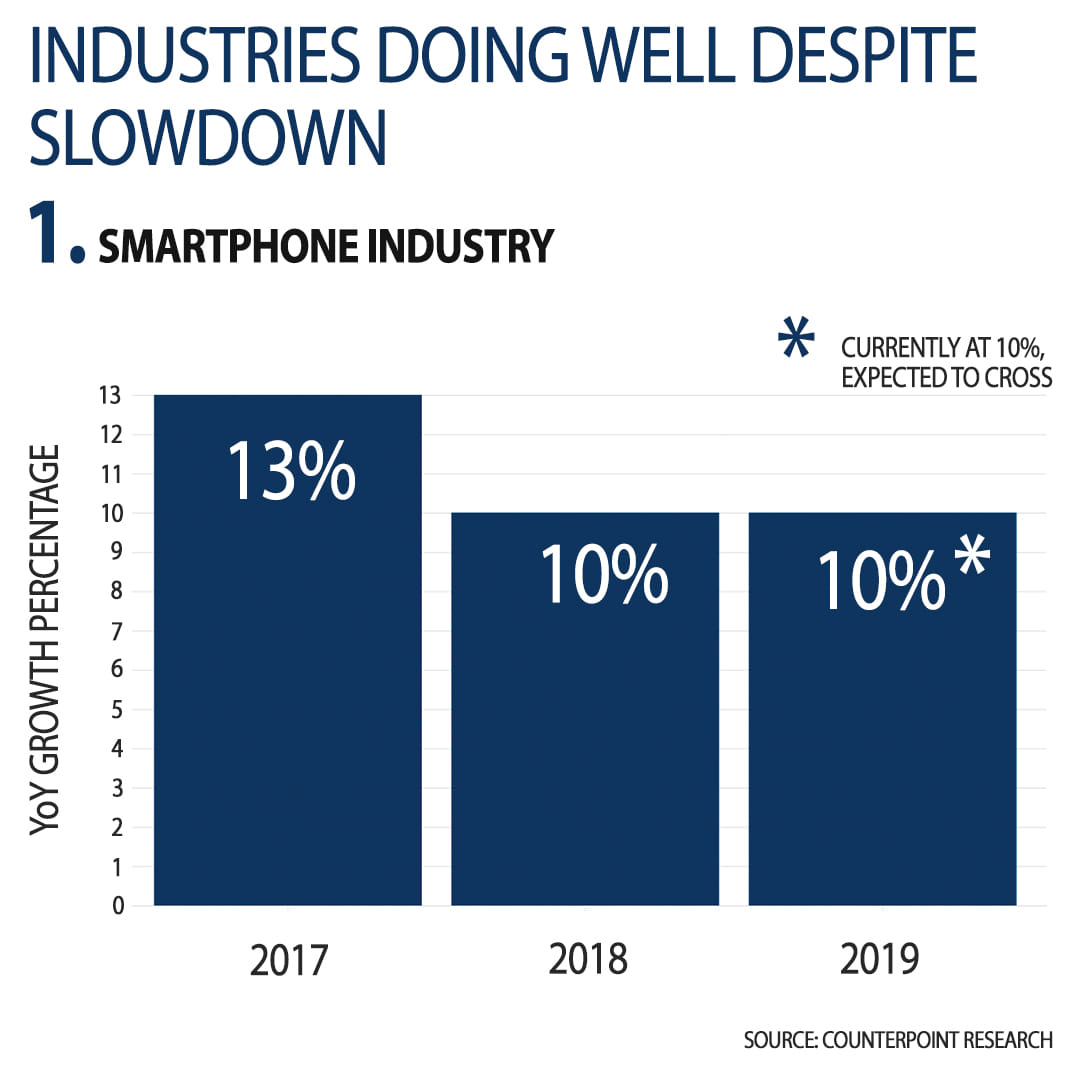

The smartphone industry, whose growth is expected to cross 10 per cent this year, has millennials to thank for its unwavering sales.

“Customers are not only buying phones for the first time, they also tend to replace them quickly. For low-budget phones, costing between Rs 5,000 and 7,000, we’re seeing a replacement rate of around 10 months,” said Karn Chauhan, research analyst at Counterpoint Research, which tracks smartphone sales in India. Expensive phones see a slower replacement rate of about 13-15 months, Chauhan added.

According to Counterpoint’s research, the smartphone market registered a 13 per cent year-on-year growth in 2017, and 10 per cent in 2018. As of October 2019, growth has equalled the 2018 figure, and is expected to cross it by the time the year ends.

“Mobile manufacturing companies are constantly changing their internal memory and speed to cater to the demand, which hasn’t seen a dent,” Chauhan said. “Most people buying phones at this rate are tech-savvy 18-30-year-olds.”

India’s economic slowdown comes on the heels of an internet revolution that is driven in large part by this demographic. In 2018, India’s internet usage registered a growth of 18 per cent, and the total number of internet users is expected to cross 672 million by the end of this year, from an estimated 566 million in December 2018.

Smartphone makers and data providers, well aware of the internet’s widening reach, are trying hard to keep up.

“There’s a phone to cater to every budget. Every week the market is seeing 10-15 new phones being launched, and every phone caters to different income-level groups,” said Chauhan.

The evolution of the smartphone places it at a unique position in a typical user’s hierarchy of needs — smartphones are now the primary screen Indians use to access the internet, watch videos and play games.

“This means smartphones are increasingly becoming a staple for Indians, and choices to replace phones are more need-based than anything else,” said Chauhan. “It’s not necessarily a style- or status-related buy.”

Also read: India is the new lab for US tech giants to test apps before global release

Streaming services such as Netflix, Gaana and Saavn

The age of the internet has also given rise to multiple over-the-top (OTT) media streaming platforms such as Hotstar, Netflix, AltBalaji, and their musical counterparts like Gaana and Saavn.

Most streaming services are only accessible through paid subscriptions, with some offering an alternative in content interspersed with advertisements. The sector appears to be making healthy progress, estimated to grow by 21.8 per cent every year and reach $1.7 billion by 2023.

“With the millennials driving the music streaming revolution in the country, our customer profile also reflects the same,” said Prashan Agarwal, CEO of Gaana.

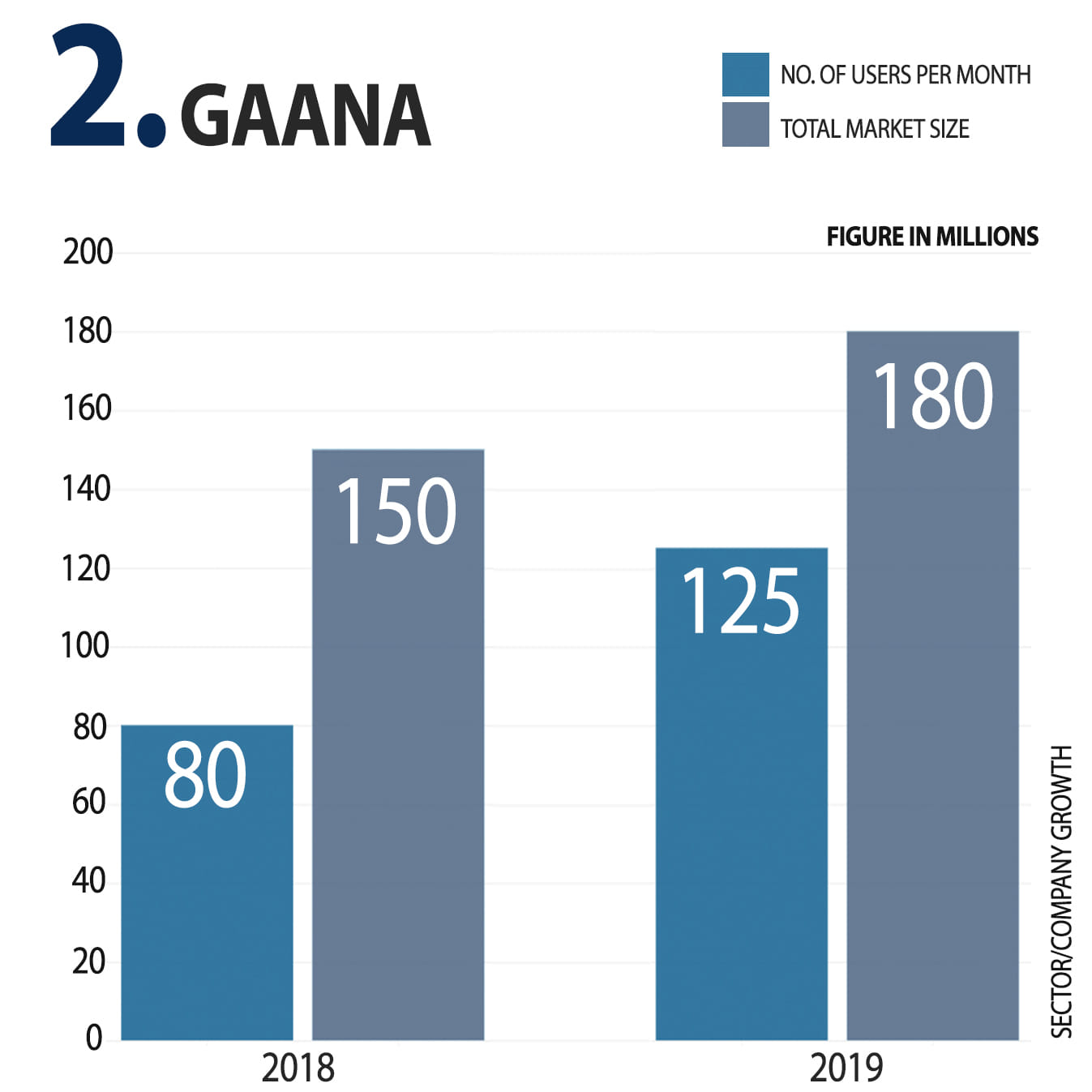

Gaana recently registered 125 million active users per month, out of a total music-app market of 180 million. The app had 80 million subscribers in 2018.

“The majority of our customers are in the age bracket of 15-25 years,” Agarwal added.

It was reported this April that Hotstar, a primarily ad-supported platform that offers premium ad-free content to paying customers, had totalled 300 million subscribers four years since launch.

The curious case of cinema

However, the convenience of streaming doesn’t seem to have dimmed the charm of catching movies at cinema halls.

Films like Kabir Singh and Uri made record-breaking box office collections this year, at Rs 276.34 crore and Rs 244.01 crore, respectively.

Other movies like Mission Mangal, Chhichhore, The Lion King and Dream Girl notched stunning openings too, with F&B sales achieving robust growth as well.

“Footfall has increased by 25 per cent over the last financial year largely because we have increased the number of screens, acquired a new chain in southern India,” said PVR Cinema’s chief financial officer Nitin Sood. “Around 6-7 per cent of the growth has come from existing outlets whereas the rest of the growth has come from the additions.

“We have not seen any change in the spending patterns of the consumer,” Sood said. “The spending on food and beverage has remained the same.”

Trade analysts in the entertainment business said cinema tends to do well during periods of recession.

“The boom could point towards depression in the economy as well as people watching more movies when under stress,” said Bollywood trade analyst Komal Nahta.

Also read: Apple enters Indian TV market with Rs 99-a-month streaming service

Demand for dairy on the rise

Even though growth in the Fast Moving Consumer Goods (FMCG) sector has slowed by 6.5 percentage points between July-September 2018 and April-June 2019, some segments have beaten the trend.

“Not all FMCGs have done badly. Colgate, Britannia have all shown positive growth rates, but they are muted,” said Arvind Sinhgal, chairman of management consultancy Technopak.

“On the other hand, you have brands like Khadi and Amul, which have done exceptionally well, showing growth of more than 20 per cent quarterly,” he added.

Amul and Mother Dairy told ThePrint that while they were aware of the current economic climate, it has left them largely unscathed.

“In the last six months, we have recorded a growth of 26 per cent,” Amul managing director R.S. Sodhi said. “Out of this, only 4-5 per cent is growth that has come due to price rise, rest is volume growth across categories.”

Thanks to small-packet-based marketing — which accounts for around 30 per cent of cream, cheese, ghee, butter and milk beverage sales — the slowdown doesn’t seem to have affected the consumption of dairy products. In fact, the revenue of Amul is at Rs 52,000 crore so far this year, up from Rs 45,000 crore last year.

State-run dairy giant Mother Dairy, which also sells fruits and vegetables, said, “There is no slowdown in demand for the categories that we operate in…”

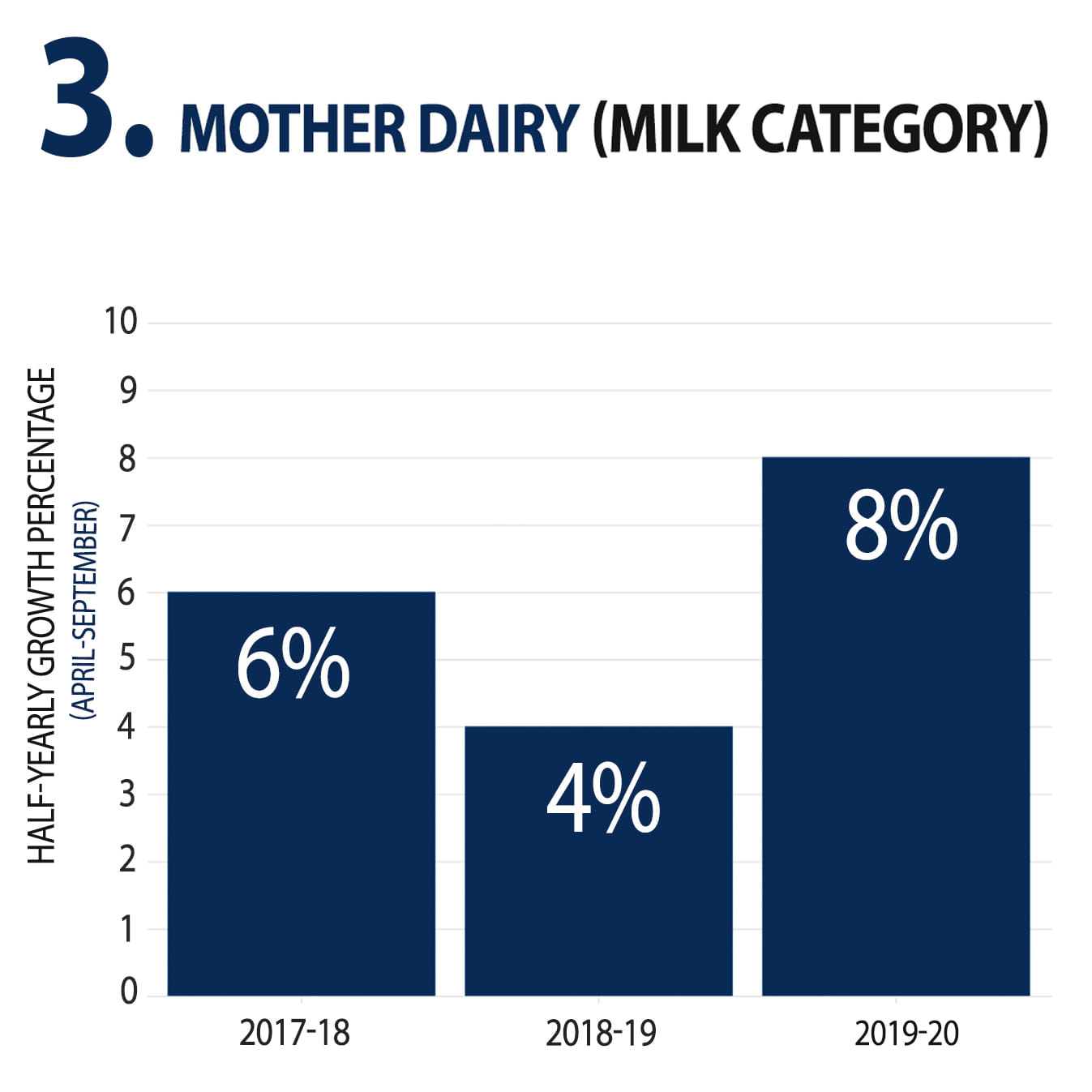

“In fact, our half-yearly volume numbers for this fiscal have seen a surge in demand, wherein milk recorded a volume growth of 8 per cent, categories such as fresh dairy beverages and curd have had a healthy volume growth of 22 per cent and 23 per cent, respectively,” it added.

In the financial year 2018-19, half-yearly volume growth in the milk category was 4 per cent between April and September. This financial year, 2019-20, the growth has doubled to 8 per cent. The category posted a growth of 6 per cent for the corresponding period in financial year 2017-18.

‘Consumers spending where they find value’

Experts and analysts studying consumer behaviour say consumer spending is still high, and primarily comes from people “not rich enough to buy cars”.

“Annual private consumption in India is nearly Rs 100 lakh crore right now, and even taking away 60 per cent for food and necessities, that’s a lot,” said market strategist and management consultant Rama Bijapurkar.

“Most of this comes from people who are not rich enough to buy cars. Even if consumption is not as robust as some would hope, it’s fair to say that it’s large — and that’s still a good thing,” she added.

“People are willing to spend, but a lot of that expenditure is discretionary,” she said. “Where the customer chooses to spend depends on what the consumer considers to be valued (benefit minus cost) at any given point in time, based on his/her priorities and what the sector is doing.”

But what’s driving certain sectors to do better than others?

“It has to do with the underlying trend of consumers investing more in services than merchandise goods,” said Arvind Singhal, chairman of management consultancy Technopak Advisors.

“Consumers are being price-sensitive because of the perceived slowdown in the economy, but also because aspirations and needs to spend are increasing,” he added. “If you want to spend a bit more on a service, like education or health, you will automatically to cut down on merchandise.

“While it’s true that the 5 per cent GDP growth rate is a disaster and we need more jobs, private consumption isn’t facing a crisis as of now,” he said. “People are still buying, and industries are still growing, even if at a slower rate than before.”

Also read: India’s dairy exports up 126% in FY19, courtesy a ‘boost’ from Modi govt scheme

yes, ghana doing well. Are you not ashamed to even count this? Another ullu.

Thankfully the authors did not claim that people are still eating inspite of slow down of Economy