Rajkot: A series of luxurious cars — from Mercedes to Porsche — zooms past on Rajkot’s Kalawadi road. Their destination, a factory for which lores have been sung in the city since National Geographic featured a documentary on it.

Welcome to Balaji Wafers, a homegrown Gujarati brand that is among the biggest in India’s salty-snacks market, holding its own against giants such as Haldiram’s and PepsiCo despite not having a nationwide presence.

In March, the company’s turnover hit Rs 5,000 crore, adding a new feather to the crown of the Virani family, whose journey began selling snacks at a cinema hall.

“The way a pebble makes ripples, our hard work created those short waves and we kept on growing,” said Chandubhai Virani, who founded the company with his brothers Bhika Bhai and Kanubhai in 1982.

“I never forced it to be any bigger,” he added, speaking to ThePrint at his office on the outskirts of Rajkot.

That Virani is an old-school businessman is evident from his office, which is bereft of a laptop or computer.

“If I get lost in my laptop all day, who will run my company?” he smiled.

Balaji Wafers is the most recognised wafers brand in Gujarat and has four factories across the country — in Rajkot, Valsad, Lucknow and Indore.

It employs 7,000 people and remains a family-run business, and its refusal to sell out to Pepsico in 2014 — the multinational’s offer was reportedly four times the company’s turnover then — is now cited as a defining moment for its commitment to its identity.

Currently, Balaji sells 50 different products. They’re currently present in 14 states, including Gujarat, Maharashtra, Goa, Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan.

The company also exports to the United Arab Emirates, Australia and the United States.

They have 2,000 suppliers, and Virani claims 80 percent of them are farmers.

It’s a matter of pride, Virani said, that local distributors have grown in wealth with him. “A business cannot thrive on its own,” he added. “It has to help all those around it.”

Also Read: Punjabi brands have cracked the next advertising war. Big agencies have to catch up

How the journey began

The roots of Balaji Wafers lie in a turbulent time, when a year of drought forced the Virani family to migrate from their village in Jamnagar to Rajkot.

That was 1974.

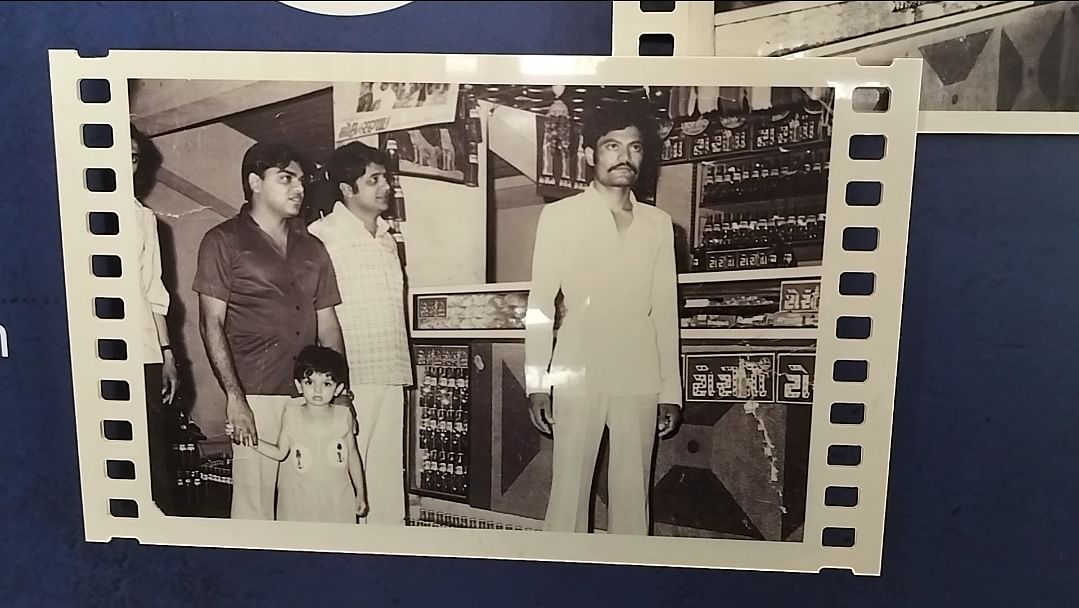

In the city, Virani, Bhika Bhai and Kanubhai, started working in the canteen of the erstwhile Astoria cinema. Within two years, they won a contract to run the canteen.

Over the next five years, the brothers decided to sell homemade wafers to the movie audiences.

“We weren’t getting a good supply of wafers, so we decided to make potato chips on our own,” said Virani. “We bought a machine that would peel the potatoes, and then the sliced pieces would be soaked in water, and the wafers made in our kitchen.”

Then something happened that, for the brothers, injected their work with a new sense of purpose.

Their father Popatbhai, Virani told ThePrint, sold his land and distributed the proceeds among his sons. “The fact that my father sold everything gave us a sense of responsibility,” he said. “To make something of the trust our father had put in us.”

The name ‘Balaji’ is an ode to their modest roots — the family chose the name because there was a Balaji temple just outside the cinema where they started their wafers business.

The brothers grew the business one loan at a time.

Their first loan was to sell the chips outside the cinema hall — in tempos and rickshaws. Once that loan was over, they took a loan of Rs 1.5 lakh to open their first factory, followed by a loan of Rs 1 crore for a factory in Valsad.

Their debt increased to hundreds of crores, and their annual turnover to thousands of crores.

According to Virani’s philosophy, for a business to thrive, profit maximisation should be secondary to value maximisation. “I was very clear, as we grew our business, that communities around us should also grow,” he said.

As an example, Virani explained how he found a way to help farmers by procuring small potatoes from them.

“We can make wafers only with big potatoes. But to ensure that small potatoes of farmers don’t go to waste, we make flakes from them and use it as an addition to various namkeen mixtures of ours,” he added. “Small potato from all over the country gets processed here.”

Learning on the job

Although the middle child, Virani — a lanky man in his 60s — holds the reins to Balaji Wafers.

His brothers, at some point, left to try their hands at other businesses, like ice cream. Virani, however, didn’t specify when they left.

In 2014, when the turnover of Balaji was Rs 1,000 crore, Pepsico made an offer.

This was around the time when two Indian snack giants had sold stakes to foreign companies — Delhi-based DFM Group (the makers of Crax) sold a 25 percent stake to the investment firm WestBridge Capital Partners, while private equity fund Lighthouse bought a 12 percent stake in Rajasthan-based Bikaji namkeens.

The Pepsico offer never made it to its logical conclusion, however, because Balaji Wafers dug its heels in on the nature of the deal.

“If they (Pepsi) had offered us a partnership, we’d have taken it. A 5-10 percent stake was fine but not more than that,” Virani said. As his company was ballooning, Virani had thought that a company like Pepsi could be a great partner to learn governance and policy and expand comfortably. “We’ve learnt all of that on our own now,” he added.

While their professional ways may have grown apart, the Virani family very much remains a united unit.

At 1 pm every day, the family members sit in the kitchen, around a huge dining table, and eat home-cooked meals with freshly cooked rotis.

In this family-run business, however, the women are conspicuous by their absence. A question as to why, didn’t elicit a better answer than “they wanted to get married and start families of their own”.

The way forward

Shyam Bhai Virani, a young director in the company, said the value of Balaji lies in the fact that a small company that blossomed from the grassroots recognises and relates with the society it’s located in, not bigger companies.

“My parents’ generation led a better part of their lives working as farmers. They (Balaji) know how to build a relationship with them, convince them, ensure they don’t go into losses,” he said. “Farmers can’t be convinced through papers or contracts. You just have to fulfil your commitment. If anything goes wrong, and prices fluctuate, you have to stand with them,” he added.

Shyam is among a new crop of leaders at the company who are breathing fresh life into it, through diversification and advertising.

The company recently launched ‘nachos’ as a product, and Virani said he’s not averse to venturing into the healthy snack sector, given he finds the right demand for it.

So far, Balaji Wafers have cut costs on marketing, which leads to cheaper production, the benefit of which they’ve transferred to the consumer — their packets have more chips, and less air.

“I didn’t market, I didn’t have sales targets. I cut costs from all these things and offered more at the same price as my competitor,” Chandubhai Virani said.

Now with digital media allowing more targeted, less expensive campaigns than television, Balaji has started making ads. “Now we’re building an image,” Virani added.

The veteran stressed upon the need to strengthen the foundation of one’s business before obsessing over growth. “Your foundation has to be strong,” he said. “Strengthen the business. Growth will follow.”

(Edited by Sunanda Ranjan)

Also Read: Dust tea to turmeric latte — how 104-year-old tea giant Wagh Bakri is juggling growth with legacy