New Delhi: This day, sixty years ago, was the start of a three-week lull during the 1962 India-China War. From 24 October to 14 November that year, fighting between both sides along the Line of Actual Control (LAC) ceased, much to India’s relief. The Army had faced multiple setbacks leading up to this period, such as the fall of Tsang Dar on 22 October, the fall of Bum La on 23 October and finally Tawang, on 24 October.

This period is important because it underscored the wide discrepancies between how India and China saw the McMahon Line — a frontier negotiated between Tibet and Britain in 1914. While New Delhi upheld the boundary line, Beijing viewed it as “illegal” and then Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai contemptuously referred to it as the “so-called” McMahon Line.

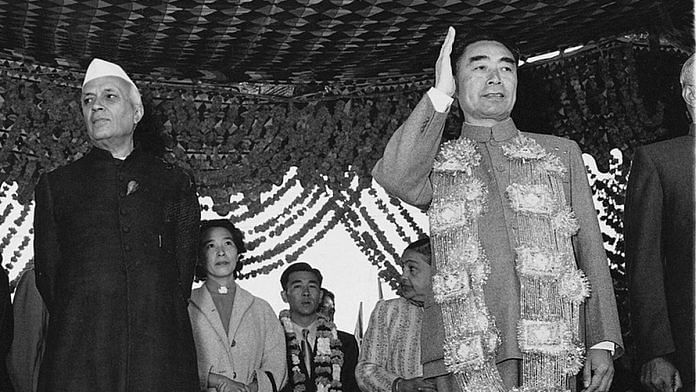

It was largely due to fundamental differences of opinion over the boundary line that led then Indian prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru to reject Zhou’s proposal for peace talks in mid-November 1962. Fighting recommenced on 14 November, the same day Nehru issued a categorical statement in Parliament rejecting Zhou’s three-point proposal for peace talks.

Letters exchanged between Nehru and Zhou during the lull period provide insights into this facet of the Sino-Indian war.

Experts have noted that Nehru’s dismissal of Zhou’s proposed peace talks, and his outreach to the US and the UK for military aid in late November 1962, hurt India’s image vis-à-vis Afro-Asian countries who were keen to see India and China come to the negotiating table.

The Soviet Union, at that time embroiled in the Cuban crisis, had also urged Nehru to accept Zhou’s offer, noted British activist and journalist Dorothy Woodman in her 1969 book Himalayan Frontiers.

Therefore, it can be argued that though no fighting occurred in the lull between 24 October to 14 November, the war continued in diplomatic forums with real consequences on the international stage.

The final rout lasted until 21 November, when Beijing declared a unilateral ceasefire.

Also Read: ‘Great mistake’ or not? Why India decided against deploying Air Force in 1962 war with China

Zhou’s offer

On 24 October, Zhou wrote to Nehru offering a three-point proposal for peace. Apart from the disengagement and withdrawal of both sides 20 km from the lines of actual control, the proposal mentioned a Chinese withdrawal in the eastern sector of the border to the north of the LAC and a guarantee that neither side would cross the line of present control in Aksai Chin. The third point was a proposal for talks between the premiers of both countries.

Even before Zhou wrote to Nehru, the Chinese government issued a press statement publicising its peace proposal to India.

On 27 October, Nehru retorted with a sternly-worded letter. “There have been repeated declarations by the Government of the People’s Republic of China that they want to settle the differences on the border question with India by peaceful means, though what is happening today is in violent contradiction with these declarations,” he wrote, insisting on reverting to the boundary as it was prior to 8 September, 1962.

Zhou turned this down, and instead suggested a return to the McMahon Line in the east and the Chinese claim line in Aksai Chin.

A ‘deceptive’ lull

Some experts suggest the Chinese offer of peace was insincere and just another form of “cartographic aggression”. Nehru himself called the lull period a “deceptive” one in reference to the way the proposal was publicised and accompanied by Chinese propaganda.

In a letter to then US President John F. Kennedy on 19 November 1962, Nehru wrote: “There was a deceptive lull after the first Chinese offensive during which the Chinese mounted a serious propaganda offensive in the name of peace to get us to accept their so-called three-point proposals which, shorn of their wrappings, actually constituted a demand for surrender on their terms.”

“The Chinese tried, despite our rejection of those proposals, to get various Afro-Asian countries to intercede with varying offers of mediation,” he added.

India, China, Japan, Pakistan, the Philippines, Cambodia, among others, were then seen as Afro-Asian countries.

Noting how Nehru’s rejection of the proposal was followed by an immediate Chinese offensive, Woodman called the lull period “misleading” because while Nehru pondered the possibility of peace with sincerity, “Chou (Zhou) Enlai, with fewer philosophical inhibitions, merely talked until the Chinese army was ready for an extensive campaign.”

Nehru’s decisions during this lull period, however, did little to enhance India’s image among other developing countries.

In a 2012 research paper for Eurasia Border Review, historian Lorenz Lüthi explained: “Nehru did not help his own country’s image within the Afro-Asian world when he sought military aid from the United States and the United Kingdom during the conflict and then refused to agree to China’s ceasefire offer.”

Final rout

Soon after Nehru issued a categorical statement in Parliament on 14 November rejecting Zhou’s proposal, intense fighting resumed on 17 and 18 November with the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) in the east pushing Indian units down to the Brahmaputra plain.

Chinese forces entered deep into Arunachal Pradesh along multiple areas like Tawang-Bomdila-Rupa, Taksing-Limeking, Mechuka/Manigong-Tato, Gelling-Tuting and Kibithoo-Walong in late November 1962.

On 19 November, Zhou declared a unilateral ceasefire to begin two days later. The PLA withdrew to the lines held before 20 October and the question over Aksai Chin was left unanswered, and remains so till date.

(Edited by Amrtansh Arora)

Also Read: Bayonets, Gorkha Khukris & hands: How Indian soldiers tried to defend Chushul during 1962 war