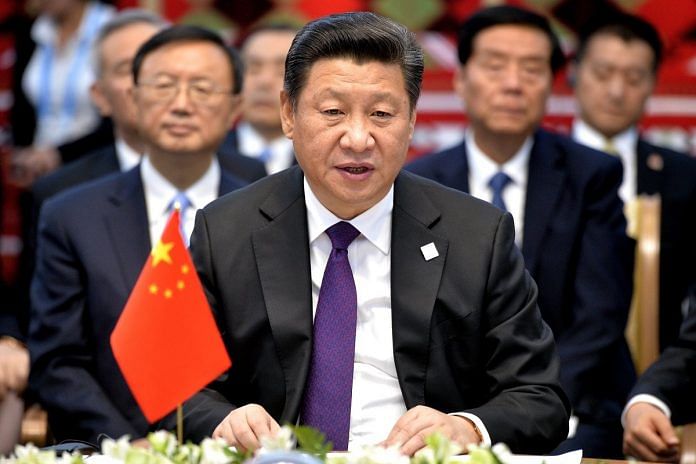

As Xi Jinping’s BRI becomes China’s pet project, there is a dramatic escalation in the country’s persecution of the Uyghurs.

China’s Muslim Uyghur population is said to be languishing in “re-education camps” in its Xinjiang province, where they are stripped off their rights to practice Islam and forced to assimilate Chinese Communist culture.

But why the Muslim-speaking world, otherwise so hawkish about the state of the “ummah” worldwide, refrains from speaking out about the persecution of China’s million-strong Uyghurs, has baffled analysts for a long time.

In comparison, the plight of Myanmar’s Rohingya Muslim minority, which has been forced to flee its home country to neighbouring Bangladesh, spawned such severe international criticism that there were calls to revoke the Nobel Peace Prize given to Aung San Suu Kyi, accusing her of being complicit in the ethnic cleansing of the Rohingya by her Buddhist-majority government.

Also read: Modi govt beats China in high-stakes battle over dam in Nepal

And less than a couple of months ago, the UN Human Rights Council not only dared bring out a report severely critical of human rights violations in Jammu & Kashmir, several UN rapporteurs castigated India for the industrial dispute in Thoothukudi in Tamil Nadu.

But despite UN bodies like the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, powerful pro-US organisations like the World Uyghur Congress as well as bleeding heart NGOs scattered all over the world, China’s Uyghurs are a mostly forgotten lot.

Sometimes the international press pays attention, but there’s little follow-up.

Certainly the Arab world, with enormous reserves of oil which the Chinese want, has hardly ever said a word.

“China is a powerful country. The Arab world has deep economic linkages with China as well as growing military ties,” Jabin Jacob, associate editor of ‘China Report’, a publication of the New Delhi-based Institute of Chinese Studies told ThePrint, explaining why no one wants to offend Beijing.

Reasons for the silence

There are two other major reasons for the silence.

The first is that China is a permanent member of the UN Security Council, and in that capacity, has the power to veto any potential criticism. Second, with president Xi Jinping’s favourite geostrategic project, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), properly underway, the Chinese are doing everything they can in keeping Xinjiang – the main port for all of China’s interactions with Europe – calm and quiescent.

“China’s permanent seat on the UN Security Council, its economic weight and its extremely nimble diplomacy combine to keep the Uyghur issue off the radar in most countries,” Jacob added.

Also read: The militaries of nuclear-armed India, Pakistan, China are suddenly friendly. Why?

He pointed out that the Chinese government had unveiled a massive propaganda exercise inside Xinjiang province as well as internationally to demonstrate that the Silk Road Economic Belt, BRI’s most visible leg which passes through Xinjiang to and from Europe, is a peaceful and stable route.

“The main thing is the need to ensure that Xinjiang remains stable and does not result in problems that embarrass the Chinese central government,” Jacob said.

But Srikant Kondapalli, professor of international affairs at Jawaharlal Nehru University and expert on China, pointed out that the Muslim world’s silence on China’s not-small Muslim population was also because “the narrative surrounding the Uyghur itself follows a double-trap approach”.

“For the West, they are projected by the Chinese as terrorists trying to split the country, while the Muslim world sees them as pork-eating, alcohol-drinking liberal Muslims who do not integrate well with the behavioural norms of their own conservative nations,” Kondapalli added.

The Uyghur problem

Certainly, the Uyghur have a problem. Because they have been part of Communist China for nearly 70 years, they have been forced to participate in the Communist Party’s atheist diktat. This means that all overt allegiance to any religion is banned (although in recent years, some relaxation has taken place, and mosques, like Buddhist temples and churches, are beginning to be allowed), and any religious practice, if at all, must be subject to the Party’s control.

Also read: China builds Gulag-like prisons for Muslims, calls them ‘political re-education centres’

Since the Chinese Communist Party in 1949 took a leaf out of the doctrine prescribed by the Soviet state (which had turned in 1917, after the Bolshevik Revolution), disavowal of religion especially meant a ban on all ritual relating to food, drink and personal habit.

Like Muslims in the former Soviet Union (who, for example, were forced to even Russify their names, with Mohammed becoming Mahomedov), Chinese Muslims were also forced to abandon their distaste for pork and alcohol – to the continued anathema and distaste of the rich, but conservative Arab world.

Saudi Arabia, for example, led the campaign for the re-Islamisation of the five Muslim-majority Central Asian republics when the Soviet Union disintegrated in 1991. But China, which learnt well the lessons from that disintegration, instead ramped up its economic strength while consolidating its territorial unity and integrity.

The control and consolidation of the Uyghur, Hui, Manchu, Zhuang, Tibetan, Mongol, Manchu and several others of the 55 minority groups recognised by the Chinese Communist Party led by Deng Xiaoping at the time, was well underway.

So despite the UN’s independent expert body, the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, which recently released a report saying it was “deeply concerned” about the detainment of Uyghurs as well as the close monitoring of their movements, there has been little reaction from either China or the rest of the world.

As for the Uyghur Human Rights Project (UHRP), based in Washington DC and funded by the US National Endowment of Democracy, its findings of rampant torture in detention and “re-education camps” in Xinjiang province – where Uyghurs were forced to eat pork, and “compelled to make pledges to consume alcohol, smoke tobacco, and tell other Uyghurs about the evils of Islam” – seem somewhat tainted because of the ongoing political tension between the US and China.

China itself has made no bones about its absolute priority, which is to keep the territory of the People’s Republic together. Beijing fears the western world is using the instrument of human rights to weaken it. So despite calls by the Dalai Lama of reconciliation and following the Middle Path, the Chinese deride him and call him “splittist”. Despite large bilateral trade with Taiwan, Beijing threatens other nations with varying degrees of isolation.

At least two decades ago, the Chinese launched its war against the “three evils,” extremism, terrorism and separatism. So when the Tibetans or the Uyghur occasionally revolted, Beijing never hesitated in implementing its “strike hard” policy. That is, any rebellion would be dealt with a heavy hand, including death.

The unequivocal message was that the Chinese state simply could not be challenged.

Ryan Barry, spokesperson for the World Uyghur Congress, told ThePrint that the US, before the attacks of 11 September 2001, refrained from describing the Uyghurs as “terrorists”, like the Chinese did.

Things changed after the 9/11 attacks. “In need of global partners in its own fight against terrorism at the time, the US accepted the Chinese narrative (on the Uyghurs), despite the fact it was not totally grounded in reality,” Barry said.

In 2009, in one of the worst bouts of violence in which at least 200 people were killed, the Uyghurs were systematically raided and targeted by Chinese authorities in a “strike hard” campaign.

As Xi Jinping’s BRI becomes China’s pet project today, there is a dramatic escalation in China’s persecution of the Uyghurs. “It seeks to establish complete control,” Barry added.

Divided Islamic world

One of the reasons for the striking silence by the Islamic world is that it is itself split down the middle. The Sunni Arab nations, led by Saudi Arabia and the UAE, have very bad relations with the leader of the Shia universe, Iran, which is happy to get even closer to its largest oil client, China, even as it is subject to serious sanctions by the western world.

As for Indonesia, the largest Islamic nation in the world, it is a neighbour of China and constantly grappling with other issues of sovereignty as well as trade with Beijing. The second largest Muslim country is Pakistan, whose “all-weather” friendship with China wholly prevents it from speaking out; in fact, Beijing has to sometimes castigate Islamabad for letting Xinjiang militancy escape into Pakistan.

But Kondapalli, the JNU professor, also pointed towards China’s nimble diplomacy on the Uyghur issue, by treating its Muslim minorities differently.

“For example, the Chinese are happy to doubly marginalise the Uyghur in comparison with the Hui group of Muslims, which eat pork. Unlike the Uyghur which don’t, the Hui Muslims are seen to be more moderate,” Kondapalli said.

Still, as the Chinese transition to a wealthy nation and challenge America’s ‘most powerful nation’ status, the Uyghurs will likely become another casualty in the games nations play. As global confrontations sharpen and the Arab world, like everybody else, looks to protect its economic interests, it is unlikely to risk offending Beijing.

For the moment at least, the Uyghur will have to learn to live on their own.

read western press all muslims turned blind because of money loan of several billions fro china!!!

THAT IS WHY!

AND NOT BECAUSE AS YOU WROTE!!!

that is why i always preffered west journalism and its media

Even in Central Asia Uighurs, Uzbeks,Tajik we were all adherent to Islam,never ever eat pork, this Kazakh and kirgis did-they are not so religious! So how these three Hidu, who is siting in India make such a statement.

you simply do not know us as a people, you do not know our values and culture.I remember as a child we were not allowed even to eat at Russians classmates(parents were scared at we will get pork)

in our culture we do not drink, some does but just like in Turkey or other muslim country!

to write such an artical to be sure you have whole context

How these 2 journalists and Srikant Kondapalli can discredit Uighurs in Islam?

even if we were under CCP as you wrote:

“Certainly, the Uyghur have a problem. Because they have been part of Communist China for nearly 70 years, they have been forced to participate in the Communist Party’s atheist diktat. This means that all overt allegiance to any religion is banned”

We uighurs alaways stayed adherant to islam!Uighurs are strong in tradition and values!! We always keep and kept respect and love to our culutre and religion!How you can write such a bull shit if you three never ever see or been in Xinjinag!

And who this is incompetent “professor- Srikant Kondapalli ?

“professor of international affairs at Jawaharlal Nehru University and expert on China, pointed out that the Muslim world’s silence on China’s not-small Muslim population was also because “the narrative surrounding the Uyghur itself follows a double-trap approach”.”

what narratives Uighur have?A?How you can write such a lie ?

I have only one thing in my mind-chinese paid you!

“For the West, they are projected by the Chinese as terrorists trying to split the country, while the Muslim world sees them as pork-eating, alcohol-drinking liberal Muslims who do not integrate well with the behavioural norms of their own conservative nations,” Kondapalli added.

China as a nation lacks transparency n prefers to work in darkness & behind the scenes. Their strength is their economic power. They have a plan b plan c etc. They have colonized Africa with their economic strength and will make all such weak nations indebted for long long time. China has minimal respect for world order and respect for rule of law in international business. China is probably the biggest threat for the world order, if they go unchecked for next decades

Although OIC members do not openly criticise China’s treatment of its Uyghur minority, because of economic and geopolitical considerations, they would share the pain of their coreligionists. Today’s China cannot behave like Stalin’s Soviet Union, locking up a million people, right where BRI brings the world into its territory. It comes across as a brittle, insecure nation, for all its wealth and power, in its treatment of its minorities. It should be possible to strike a better, more humane balance between the cultural religious, linguistic aspirations of its minorities and the protection of its territorial integrity. It is unable to abide by its solemn promise of One country, two systems in Hong Kong, which no one is planning to snatch away from it. By stubbornly refusing to open up internally, as many had hoped it would, as it became a more prosperous country, China is failing to become a global role model, which others would wish to follow. In that sense, it will never draw level with the United States in terms of global power, reach, influence.