New Delhi: The accuracy of the Union budget has been on the decline over the past five years, with the deviation in the government’s estimated revenues and actual figures reaching as much as 10 per cent in 2018-19 financial year, ThePrint has found.

Each year, the budget document that is presented by the finance minister in parliament comprises the estimated budget for the upcoming financial year, the revised estimates for the previous financial year and the actual figures for the year before that. For example, the 2023 budget presented by Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman Wednesday, contained the estimates for the 2023-24 financial year, the revised estimate for the 2022-23 year and the actual figures for 2021-22.

The estimates for the upcoming financial year typically give an idea of what the government thinks its expenditures, earnings and borrowings in that year may look like. These get revised the next year, based on an assessment of actuals, but the final tally comes in only the following year.

So a budget estimate goes through two financial years before the final and actual earnings, expenditures and borrowings are put on paper. The actual figures are a reflection of the accuracy of the budget estimates made two years ago.

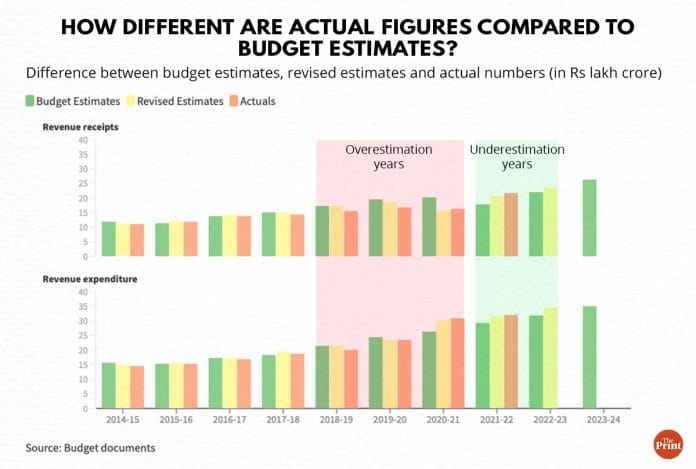

ThePrint looked at budget estimates since the Narendra Modi-led BJP government came to power in 2014 and found that the deviation in budgeted revenue earnings and actuals reached 10 per cent in the 2018-19 financial year and has remained high since. Before that the gap between budgeted estimates and actuals was in single digits or in decimal points, a scan of the yearly budget documents has shown.

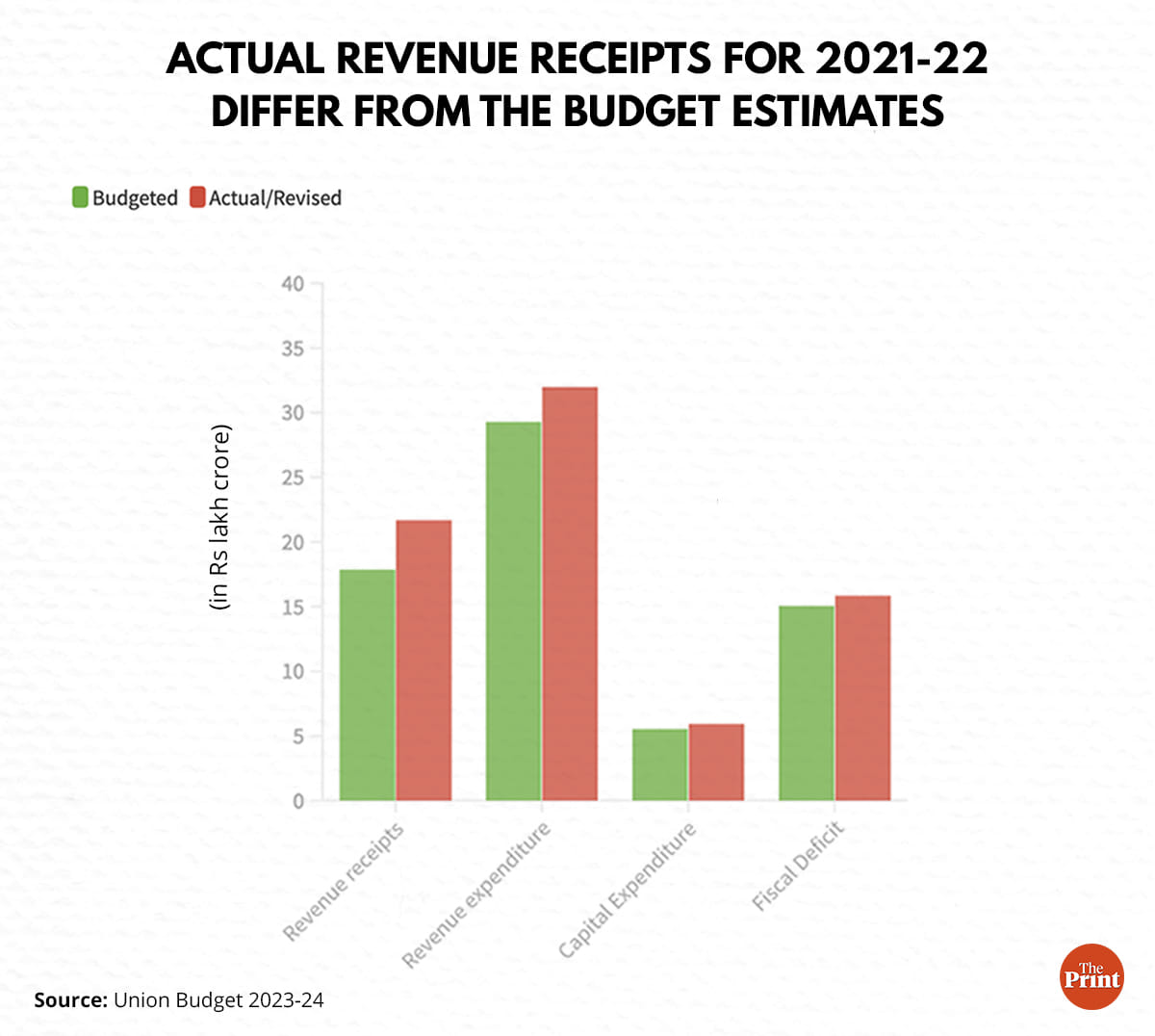

According to data available in budget documents, for the 2021-22 financial year, the government underestimated its revenue receipts by 21 per cent, its revenue expenditure by 9.3 per cent, its capital expenditure by 7 per cent and its borrowings by 5.2 per cent

This means the budget estimates presented in the 2021 Union Budget two years ago were less than actuals.

Though experts point at economic uncertainty as one of the reasons for the deviation — for example, economic slowdown before the Covid pandemic and the pandemic itself may have contributed to the gap in the past one or two years — there was a 10 per cent gap between the Union government’s estimates and actuals of revenue receipts as far back as the 2018-19 financial year.

Also read: Budget 2023: Fiscal deficit to meet 6.4% target in FY23, aim for 5.9% in FY24, says Sitharaman

What’s happening to revenue receipts

Revenue receipts refer to the government’s earnings from taxes (income tax, corporation tax, GST, custom excise and duties, wealth tax etc), as well as from non-tax revenues like profits and dividends, interest receipts etc.

According to the Union budget for the 2018-19 financial year, the government had expected to earn revenue receipts worth Rs 17.26 lakh crore, but the actual earnings were only Rs 15.53 lakh crore — a deviation of about Rs. 1.73 lakh crore, or about 10 per cent.

In the 2019-20 financial year, preceding the pandemic years which set in from February-March 2020 in India, there was a 14.2 per cent gap between the government’s revenue receipt estimates and actuals. The government had expected to earn about Rs. 19.63 lakh crores (in revenue receipts), but ended up earning only Rs. 16.84 lakh crore — almost Rs 2.78 lakh crore less than expected.

The following year, in 2020-21, it expected to earn Rs 20.2 lakh crore in revenue receipts, but ended up earning 16.38 lakh crores, an overestimation of almost 19 per cent.

In comparison, in the 2021-22 financial year — which saw the second and third Covid wave and actual figures for which were released Wednesday — the government underestimated its revenue receipts by more than 21 per cent.

The union government had expected revenue earnings of Rs. 17.88 lakh crore in 2021-22, but the actual receipts were Rs. 21.7 lakh crore — an excess of Rs. 3.8 lakh crore or about 21% — the biggest deviation the Modi government has seen in its revenue receipts so far.

In comparison, between 2014-15 and 2017-18, the government’s actual revenue receipts were always below 10 per cent. In the 2016-17 financial year for example, the actual numbers were just 0.2 per cent short of the budget estimates. It was the highest (during the 2014-15 to 2017-18 period) in the 2014-15 financial year, when it had touched 7.4 per cent.

What explains this

As the name suggests, revenue receipts depend largely on the functioning of the economy, more people or businesses earn more incomes, provide for more tax revenues. Similarly more public consumption entails more consumption taxes like GST, union excise, duties.

According to Manish Gupta, associate professor at the Delhi-based National Institute of Public Finance and Policy (NIPFP), the deviations of actual numbers from budget estimates could probably be explained by uncertainty.

“Deviation could be explained by slowdown in economic growth during 2018-19 and 2019-20, may be the reason for deviation in actual revenues from budget estimates. This was further aggravated by the pandemic in the next two financial years,” Gupta told ThePrint.

Deviations between revenue earning estimates and actuals may also impact state funds. About 41 per cent of the Central government’s earned taxes go to states, according to the recommendation of the 15th Finance Commission.

If there is a mismatch in the tax collection data, it may also impact the money states are likely to get from the Union.

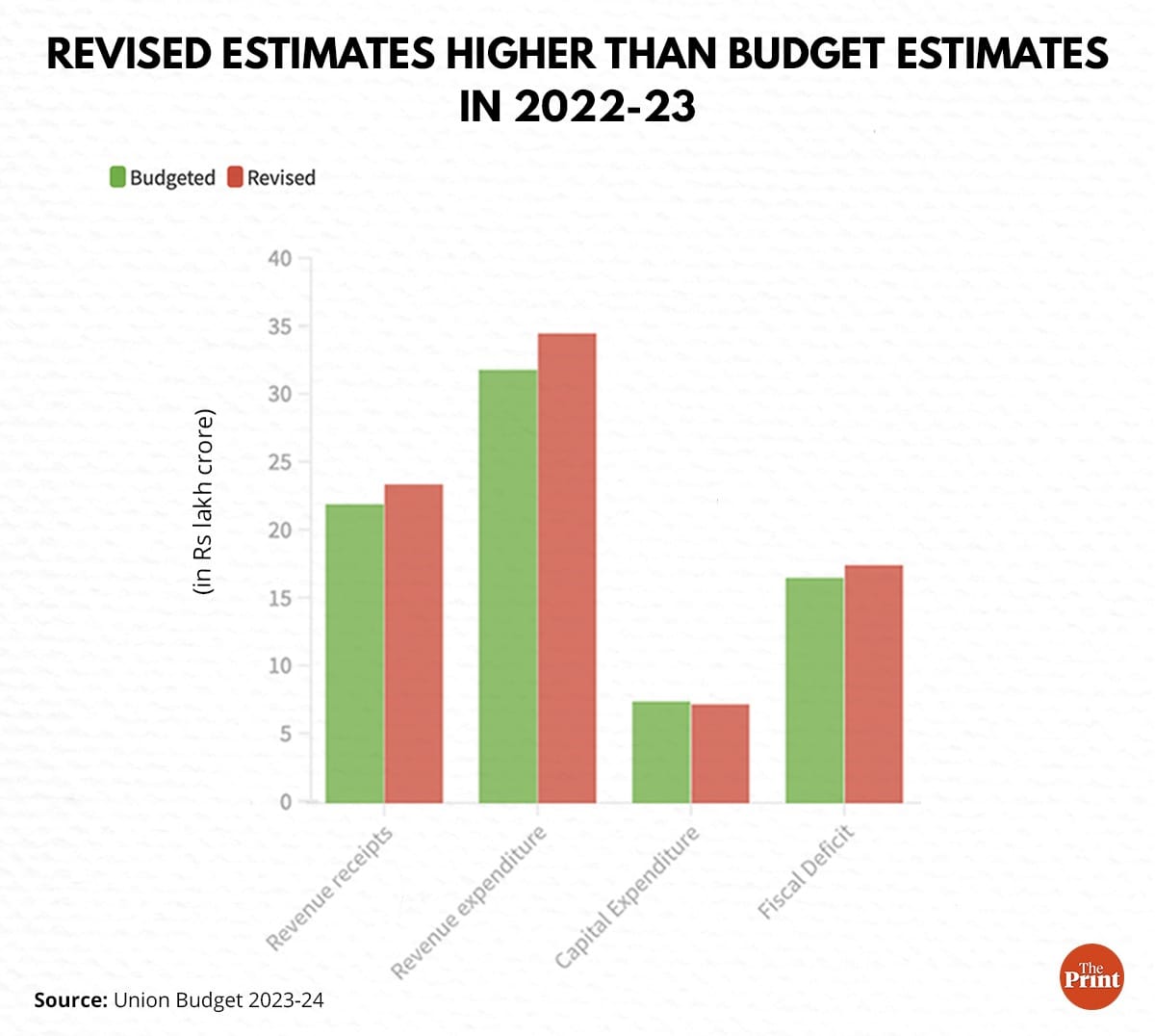

Revised estimates for the 2022-23 financial year show that the government has underestimated its tax revenue by 8 per cent. Revised figures for corporate and income taxes show that the budget figures were underestimated by more than 16 per cent. In the 2022-23 financial year therefore, states are likely get more money than was expected in the budget estimates.

A study by ICRA Limited, Moody’s investor services firm, had shown last November that the Gross Tax Revenues would surpass the budget estimates by Rs. 3.1 trillion (or Rs. 3.1 lakh crore).

This means that the states would get additional amounts of devolution funds, which could impact the states’ borrowings, the ICRA had said in a release.

“The Central tax devolution for FY2023 in the revised estimates is in line with our expectation, in addition to which Rs. 334 billion is being provided as an adjustment for prior years. We estimate the amount of tax remaining to be devolved to the states in Q4 FY2023 at a substantial Rs. 3.4 trillion, based on which we believe the state government security issuance in this quarter will trail the indicative amount”, Aditi Nayar, chief economist, ICRA, said in a press statement Wednesday.

(Edited by Poulomi Banerjee)

Also read: Budget 2023: An election-year bonus for the super-rich. No, Modi govt hasn’t lost it