Loud music greeted Aditya as he walked into my sister’s house where Amrita and I had been staying since moving back from Kuala Lumpur. Our home was getting ready and I used to spend almost the entire day overseeing the work, cleaning up and setting the house in order. My sister’s house was not only conveniently located, but also a place of great comfort, as we adjusted to the ways of the city and a new life.

Aditya walked in to see Amrita grooving to the hit song of the year ‘Tu cheez badi hai mast mast’ (from the film Mohra that had just been released with Bollywood stars Raveena Tandon and Akshay Kumar). He had been really apprehensive about the move and we had spent hours discussing the impact on Amrita whose life was going to be turned upside down—from making new friends and going to a new school, she would also have to give up many of the luxuries that we had got used to in Kuala Lumpur. As for Amit, he was already in India, studying at the Mayo College in Ajmer and for him, it would have been less of an upheaval. That day, when Aditya saw Amrita jiving and dancing and singing with such abandon, he grinned and said, “She’ll be all right.”

Soon Aditya packed his bags and joined us in Mumbai and Concord, tucked away in a quiet corner in Bandra, became our home. He officially took charge in September 1994, joining the HDFC office at Sandoz House. It was a far cry from the swanky Citibank workspaces that he was used to. Broken chairs, half-done furniture, makeshift partitions—that is what his office looked like—not just for Aditya, but for all the people from Bank of America, Merrill Lynch, Reserve Bank of India that he was trying to get on board. Everyone was coming into an office that was nothing like the places they had worked in earlier. Everyone knew that they were all buying into a dream that could take off or fail. And fortunately, everyone was united by a common vision. But it was a hard battle every day.

Also read: Yes Bank’s Rana Kapoor preferred Black Label, could drink half a bottle without getting…

On the family front, I could see the toll it was taking on Aditya. Every day was a new challenge. There was this time he met some potential investors who could not even pronounce the name of the bank. Another time he went to meet a senior industrialist who kept him waiting for over half a day. After being considered among the top performers at Citibank, he was being dismissed as a flash-in-the-pan. That hurt, as did the huge adjustments that we had to make on the home front—be it the tiny living space after the sprawling home we had in Kuala Lumpur or some of the basic comforts that we had taken for granted at Citibank.

There was also a lot of self-doubt. Would he be able to deliver or would it all come crashing down like a house on fire? Would he be able to convince the best people to join and then stay with the bank? And the one question that he asked me repeatedly: “Smiley, have we made a mistake?” But we could not show any of this to the world outside.

The worst days would be when one of his ex-colleagues from Citibank would call him. Their conversation would invariably turn to all the things that he had given up to come to Mumbai. And my task would become a hundred times more difficult. Years later, I asked him about the early years that took such a toll on all of us. Was it that he had underestimated the challenge of setting up a bank in India? Or was his confidence shaken by the number of hurdles that came his way?

Also read: Much before Punjab & Maharashtra Bank, there was the BCCI – Bank of Crooks…

“Neither,” he said. There was never any doubt in his mind about the opportunity or the expertise of the team. “The implementation was going to be tough but if we did it right, we could create history,” Aditya said. No country can move ahead with just public sector banks and foreign banks. You needed large private sector banks. All the indecision, anxiety, and gloom—it was not about the opportunity or his capability and that of the people around him, but whether he was right to leave a cushy job and come to India.

Those were the doubts weighing heavy on his mind as he went to work, met clients, and worked out a way to keep our family life stable and comfortable. Every day, when he came back from work, I sat with him for an hour or more, just talking to him and boosting his confidence. I found my own little ways to keep myself sane and happy too. It was not as if his work was the only thing that we had to deal with at the time. His parents were ill. And Amrita was having a tough time at school, so my hands were full.

But it was also an exciting time. Just as Aditya was getting to know the new system and the new norms of banking, the bank and its team were also getting to know him. Very soon, word went around that if you were going out with the boss, you had to carry a wallet, because he never carried one. Even now, I keep the money when we go out.

Another practice that soon became an Aditya trademark was his fixation with punctuality—he never wears a watch but he is never late. His team knew that the worst start to a morning was when the boss saw you slip in late. He would make life miserable for those who missed their meeting schedules or didn’t clock in on time, even if it were just a few minutes.

Also read: Front companies, corrupt govts, banks that vanish overnight — how global kleptocrats unite

Aditya also never carries a phone. It used to irritate me no end, because I was never able to get a hold of him when I wanted to. But nothing I did would convince him to carry one, until one day, I bought him a phone. Do it for me, I told him.

He took the phone without a murmur and regularly carried it to office too. But what did he do with it? At some point in the day, he would dial my number and if, for any reason, I didn’t pick up, he would switch it off and stuff it into the safe in his room. After that, the only time the phone came back into his hand was when he left for home. Neither could I return his calls, nor could I call him when I wanted to.

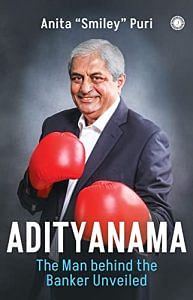

This excerpt from ‘Adityanama’ by Anita Puri has been published with permission from Jaico Publishing House.

This excerpt from ‘Adityanama’ by Anita Puri has been published with permission from Jaico Publishing House.