Thank you dear subscribers, we are overwhelmed with your response.

Your Turn is a unique section from ThePrint featuring points of view from its subscribers. If you are a subscriber, have a point of view, please send it to us. If not, do subscribe here: https://theprint.in/subscribe/

Just back from Ladakh, I just need to shut my eyes to see the barren, awe-inspiring mountains. The otherworldly Pangong lake and its surreal blue calm will stay in my mind space for a long time. The transcendence that I experienced in the rugged Ladakh can only be matched by the story of this man who drove us to far flung places each day for 7 days.

I feel thankful to have met a man called Karma Tenzing. After two days of driving us in Ladakh, it took a road scuffle to get us talking. He got off the driver’s seat, at a point where a cavalcade of motor cyclist had blocked the road and were yelling about something that I did not care to comprehend. Karma took on a burly young man and stood his ground even when other motorists raised their voice in what seems like a heated argument. He finally got the road cleared. As he took the driver’s seat again, he swore under his breath, and in his delightful Ladakhi accent proclaimed that these young boys with expensive bikes think that they own the road. “What if they had physically harmed you?” I asked him….” They wouldn’t …I have served in Siachen…I can kick the hell out of them if I want to.”

This sounded interesting. The conversation ensued. Karma Tensing spoke in short sentences. No frill, no fluff only condensed, bare, rugged nuggets of wisdom. The kind of wisdom that comes from life that has been a heroic struggle. The only child of a Tibetan refugee couple, his father died on the way as they made an escape from Tibet. Raised by his mother who had to work as a coolie and a labourer to make ends meet. As a kid he would often wonder where would he get firewood from lest something happened to his mother? He lived on gruel made of rice and sometimes ate Yak meat. He pronounced Yak from the epiglottis. With no education he started doing odd jobs very early and brought home food or some money. It was striking that Karma did not speak of his past with any sadness. It was as if the events in his past were weeds which he trampled and found a way amidst the wilderness of poverty. Chaltey raho …he would trail off.

His recruitment as an Army Jawan changed his life. He took up paratrooping to get extra allowance and drove trucks to make some extra money when he came home for holiday.

Karma Tenzing’s stories riveted us, and the big brown mountains and clear streams provided inspirational visuals. The narration of his struggles was with joy and confidence and with absolutely no bitterness. Never even once, did he use a preachy tone and spoiled his joyful discourse. “When the water of Shayok River got turbid, we would drink it in a glass with some sugar and pretend it was tea” he reminisced as we crossed the Shayok River.

“Keep walking…and you’ll surely reach somewhere” he said rather plainly. The best part of his narration was when he told us about his sons. He had managed to educate all three of them in some of the good colleges of the country. He wanted a life of dignity and respect for them for which he did all that he could. His army anecdotes and experiences were mesmerising. As a member of Ghatak Dal, he described the raids on enemy artillery position with relish.

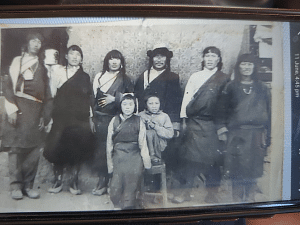

Well into his sixties, lean and athletic he lives by the credo- “keep walking”. What makes people like him so resolute? I guess faith helps. Karma’s belief in doing what his duty requires comes from being a practising Buddhist. May be being in such trying circumstances and having a mother who refused to give up etched that never say die attitude in him. He showed me pictures of his relatives in Tibet whose whereabouts he did not know. The colourful Buddhist prayer flags fly atop the terrace of his concrete house sending prayers for all sentient beings to the skies. “I want to be reborn in Ladakh and be an army officer” he added softly.

There needs to be a word for the tiredness and subtle changes you feel in yourself at the end of a holiday.

These pieces are being published as they have been received – they have not been edited/fact-checked by ThePrint.