New Delhi: Upset over the debilitating economic situation in Turkey, hordes of people took to the streets in Istanbul and Ankara this Tuesday, calling on President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and his AKP Party-led government to resign.

“AKP, this is our country, go away,” protesters chanted in Istanbul in response to high inflation rates and yet another crash of the lira, Turkey’s currency.

The latest developments in the Turkish economy are a result of the unorthodox approach to inflation taken by the country’s leadership.

ThePrint explores how Erdogan’s politics behind keeping low interest rates has triggered problems for Turkey’s economy.

Economy in trouble

Last week, the Türkiye Cumhuriyet Merkez Bankası’ (TCMB) or Turkey’s Central Bank announced a cut in its key policy rate, impacting the borrowing rates of ordinary Turks. It was the third cut in three consecutive months.

While the reasoning behind such a rate cut was a promise “to deliver growth”, it has on the contrary been driving the country’s economic problems, primarily through inflation.

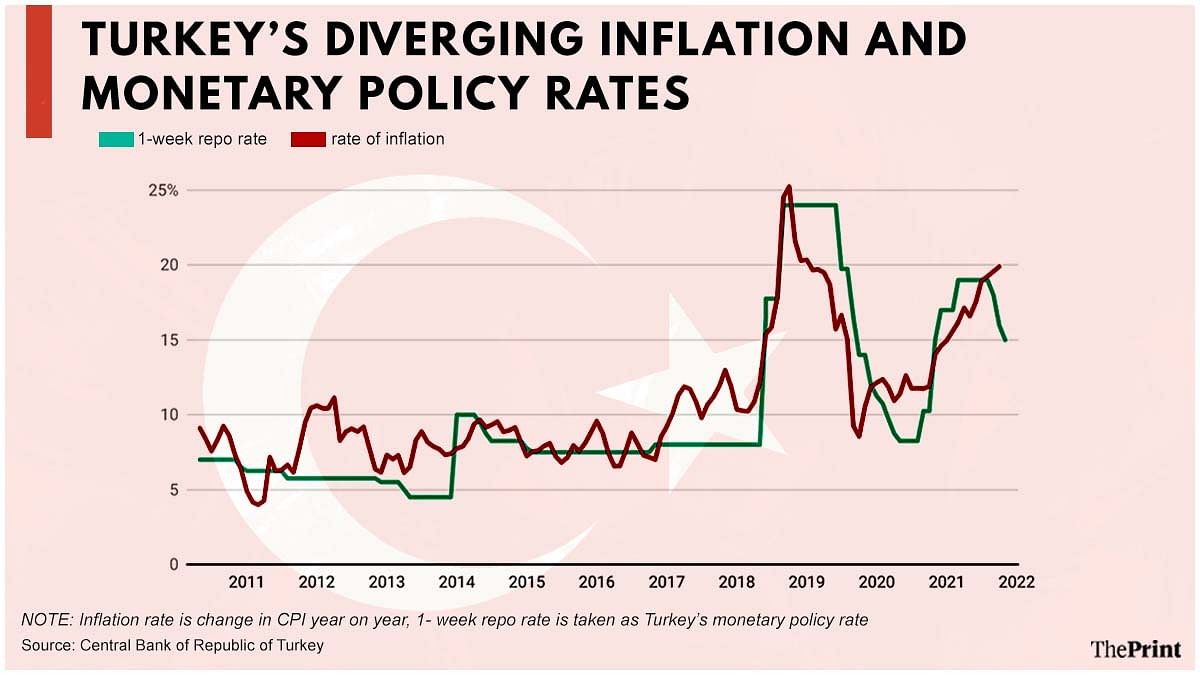

Since March 2021, Turkey’s key policy rate or what the country calls the ‘1-week repo rate’ has been slashed by 400 basis points (from 19 per cent in March to 15 per cent in November 2021). At the same time, inflation has jumped up by 370 basis points (16.19 per cent to 19.89 per cent), according to statistics shared by the central bank.

Inflation rates are impacted by demand–supply mismatch. When people have the money to buy, they can demand goods and services, but during short supplies, prices move up.

The monetary authority of a country, usually the Central Bank, keeps a check on inflation by controlling demand through managing the borrowing rates.

So when the central banks increase the borrowing rate, the commercial loans become dearer, which contracts the purchasing power in the economy. During non-inflationary times, when producers have more supply, central banks ease these interest rates so people have money to buy these goods.

In Turkey, however, the exact opposite has been happening over the last six months.

Central bank echoes Erdogan’s tone

The Central Bank has been echoing what President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, a self-declared “enemy” of interest rates, has been saying. Erdogan believes that high interest rates slow economic growth and fuel inflation.

Even in the latest cabinet meeting, justifying the recent rate cuts, he had said, “We were either going to give up on investments, manufacturing, growth and jobs, or take on a historic challenge to meet our own priorities.”

That, however, has done little to help the economy.

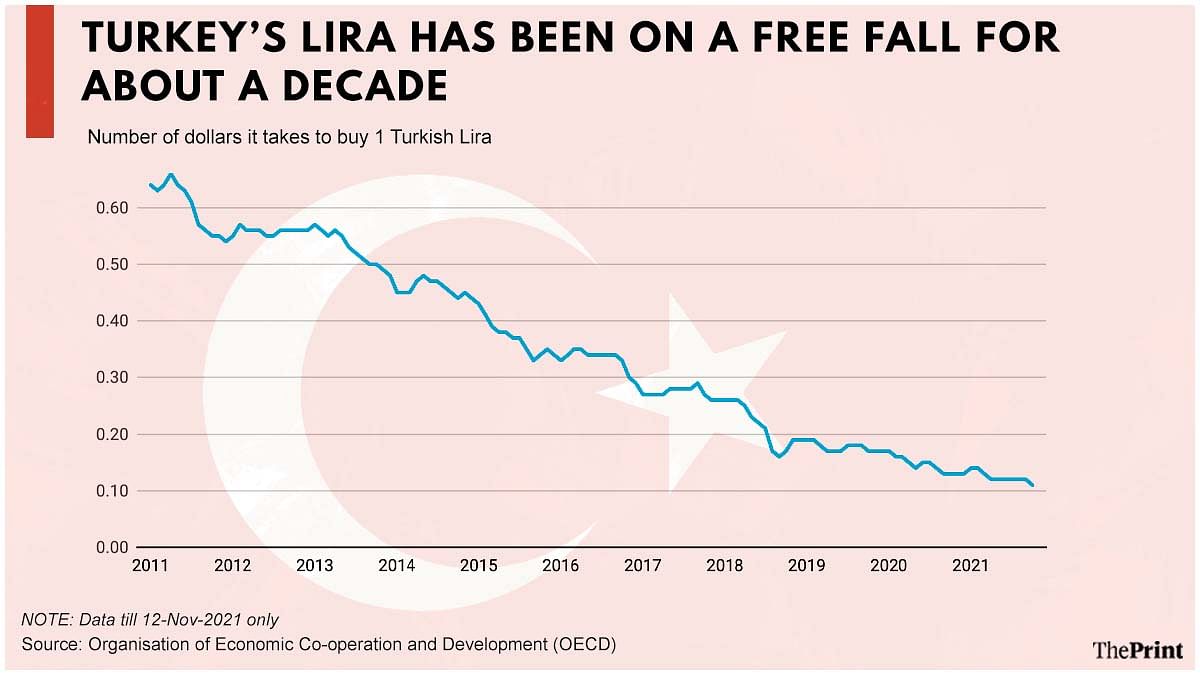

On Tuesday, Turkey’s lira fell to a new record low at 12.73 against the US dollar. The lira is the worst performing currency this year, having lost 40 per cent of its value so far and falling 17 per cent since the start of last week.

The central bank had maintained at the beginning of the financial year that it would go for a “full-fledged inflation targeting strategy”, in which it would put efforts to gradually converge the inflation rate close to five per cent.

Despite keeping a tight control on the policy rate, however, the economic situation in Turkey seems far from ‘price stability’ — the TCMB’s motto.

In the October issue of its quarterly inflation report, the TCMB has justified these rate cuts, saying Turkey’s inflation rate is majorly being driven by supply-side factors and are transitory in nature.

“Monetary tightening continued to have a decelerating impact on credit and domestic demand, and emphasized that the tightness in the monetary stance had started to have a higher than envisaged contractionary effect on commercial loans,” the report had said. “Accordingly, judging that a revision in monetary policy stance was needed, the committee decided to cut the policy rate by 100 basis points.”

Experts on the matter do not agree.

Selva Demiralp, who teaches Economics at Koc University in Turkey’s Istanbul, expressed her concerns with TCMB’s latest communications in an op-ed published by the BBC.

“Let’s not forget that as the TCMB moves away from economic fundamentals and tries to explain the mistakes made with even more faulty reasons, panic increases and heavy prices are paid in the economy that cannot be compensated,” she wrote in her opinion piece.

Turkey’s inflation has also been in double digits for most of the last four years because excessive current account deficit has caused the lira to consistently depreciate —currency depreciation makes imports more expensive, fuelling inflation. This, along with the post-pandemic burst of demand, has driven the recent surge.

Also read: What is the Cyprus-Turkey issue Jaishankar referred to after Erdogan’s Kashmir remark at UNGA

Turkey’s rising inflation

The pressure to lower interest rates has not come with envisaged economic consequences especially with respect to inflation.

The country reported a 19.89 per cent annual growth in its consumer price index, which is the highest among the key emerging markets where only Turkey and Brazil report a double-digit inflation (see chart).

Turkey, however, has prolonged high inflation rates throughout the Erdogan regime — since February 2017, the CPI has largely remained in two-digits.

“They (Turkish government) say inflation is around 17-20 per cent but I think it’s about 30-40 per cent. The prices of common items are climbing every week. I’m very anxious about our economy and I think we’re heading for a crisis similar to the one in 2018, if not worse,” a professor at a public university in Istanbul told ThePrint on condition of anonymity fearing government action.

Ground reports by international publications show that soaring prices are in fact hurting the citizens of Turkey, who are struggling to buy food at stable prices. To put in context, the average retail prices have risen by 20 per cent in Turkey — almost four times more than the 4.48 per cent increase in India.

Erdogan’s authoritarianism

Turkey faced a similar situation in 2018, when inflation rates skyrocketed as high as 25.24 per cent in October that year. The Central Bank had back then exercised its authority to increase the interest rate and it pushed up the one-week repo rate to 24 per cent, going against President Erdogan’s will.

The tight monetary policy resulted in the reduction of inflation rates from 25.24 per cent in October 2018 to 8.55 per cent in October 2019.

So why not do the same thing now?

In Turkey, not agreeing with the President’s stance comes with a cost. Though the TCMB is an independent institution, Erdogan has removed four of its governors in the last two-and-a-half years for not agreeing to his demands.

He even called some former governors “traitors” for not lowering interest rates enough.

Following his re-election in June 2018, Erdogan claimed the exclusive power to appoint central bank rate-setters and named his son-in-law Berat Albayrak as finance minister.

Last month, after a meeting with the president, the TCMB sacked three key policy makers who opposed Erdogan’s demand for a further rate cut.

In fact, the President is already losing confidence in the latest governor — Sahap Kavcioglu — who was appointed just seven months ago, Reuters had reported.

In Erdogan’s tenures, the country has also been slipping into an increasingly authoritarian one. Turkey has seen a major decline from an “electoral democracy” in 2010 to an “electoral autocracy” in 2020, according to Sweden-based independent research institute V-Dem and this has raised credibility issues with its institutions, including the TCMB.

The professor ThePrint spoke to also explained how faculty in various state-run universities are afraid to teach basic monetary policy theory to students, fearing some may be stooges who will report them to the government. “About 10 or 15 years ago, it was much easier to talk about the economy in Turkey. Now, we are afraid,” the professor said. “I know what Erdogan says about high interest rates causing inflation is totally wrong but when my students come to ask me if it is true, I am scared to answer. I always end up telling them the truth but I have been warned that some could end up reporting me to the government and I could face action.”

Erdogan endorsing ‘Islamic economics’?

Though Turkey is a secular country, Erdogan’s politics thrives on promoting Islam. His support to the infamous and now banned Egypt-based Islamist organisation, Muslim Brotherhood in (which he withdrew later), the reversion of the Church Hagia Sophia to a mosque, are some of the evidence to this.

Some experts now believe that it is his religious beliefs that are driving Erdogan’s economic policies.

For instance, in Islam, Riba prohibits usury, a practice of charging exorbitant interest rates is severely prohibited.

In his book, Why as a Muslim, I defend liberty, Mustafa Akyol writes, “In mid-2010, after a decade of economic success thanks to pursuing conventional economics and institutional reforms outlined by global markets and the European Union, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan reverted to his old Islamist ideology. That included a conspiratorial rhetoric about the ‘interest system’, or ‘the mother and father of all evil’”.

Akyol is a senior fellow on Islam and Modernity at the Cato Institute, an American think-tank based in Washington DC.

Speaking to ThePrint, Akyol explained how Erdogan has changed his stance on interest rates. “President Erdogan’s dogmatic insistence on his peculiar theory about interest rates, which comes from the Islamist ideology that he had claimed to have abandoned in the early 2000’s, when he was embracing the European Union path, which, at time, worked for him”, he said.

Even in the present day, Erdogan hasn’t let go of Islamic values. In January, Turkey’s state-controlled top religious authority, the Directorate of Religious Affairs, passed a fatwa (ruling) stating that interest-based home loans were exempted from the ban on usury, so long as they were for the purchase of real estate in a government housing project.

The Istanbul professor believes that Riba is just one of the factors impacting Erdogan’s distaste for interest rates. .

“Riba is important for the president’s voter base — they are mainly conservative and fundamentalist. But I don’t think this is the main reason,” the professor said. “For quite some time, Erdogan tried to keep the lira afloat but now I think he is taking drastic measures because there is not enough foreign currency in the central bank. So now they are trying to focus on export-led economic growth to get as much money as they can.”

In April, the Turkish central bank’s net international reserves fell to its lowest level since 2003 at $10.68 billion.

According to Mustafa Metin Basbay, teaching fellow at SOAS University of London, Erdogan wants to end Turkey’s need for foreign financing even at the cost of the lira.

“Turkey ran a huge current account deficit for a very long time, financed via excessive foreign borrowing. Now, neither global liquidity conditions nor Turkey’s geopolitical position (especially vis-a-vis the US) allows the country to continue borrowing at similar rates,” Basbay said. “So, the choice Turkey is facing is either to hike interest rates dramatically to continue attracting capital inflows or to end its need for foreign financing by closing its account deficit at the cost of depreciating the Turkish Lira and declining purchasing power of Turkish citizens. Erdogan seems to be choosing the latter.”

Asked what this spells for the future of the Turkish economy, he told ThePrint in an email: “Turkey has been running a current account surplus for the last three months. However, given the already high external debt volume, the country’s surplus is far from enough for servicing debt obligations.”

“If the account surplus, along with a high investment rate, can be maintained until spring, combined with rising tourism revenues, sentiment for Turkey in international financial markets can dramatically change,” he added. “This is an optimistic and but not impossible scenario.”

(Edited by Arun Prashanth)

Also read: What press freedom crackdowns from US to China to Turkey mean for investors