New Delhi: “Running this puts Black @NYTimes staff in danger.”

On 4 June, dozens of current and former New York Times (NYT) employees posted this to their Twitter timelines as they carried out a co-ordinated protest against a now infamous op-ed that had been published by the media house.

What eventually became a mini movement on social media and resulted in the resignation of NYT‘s opinion editor James Bennet four days later reportedly started as a 15-minute conversation on Slack.

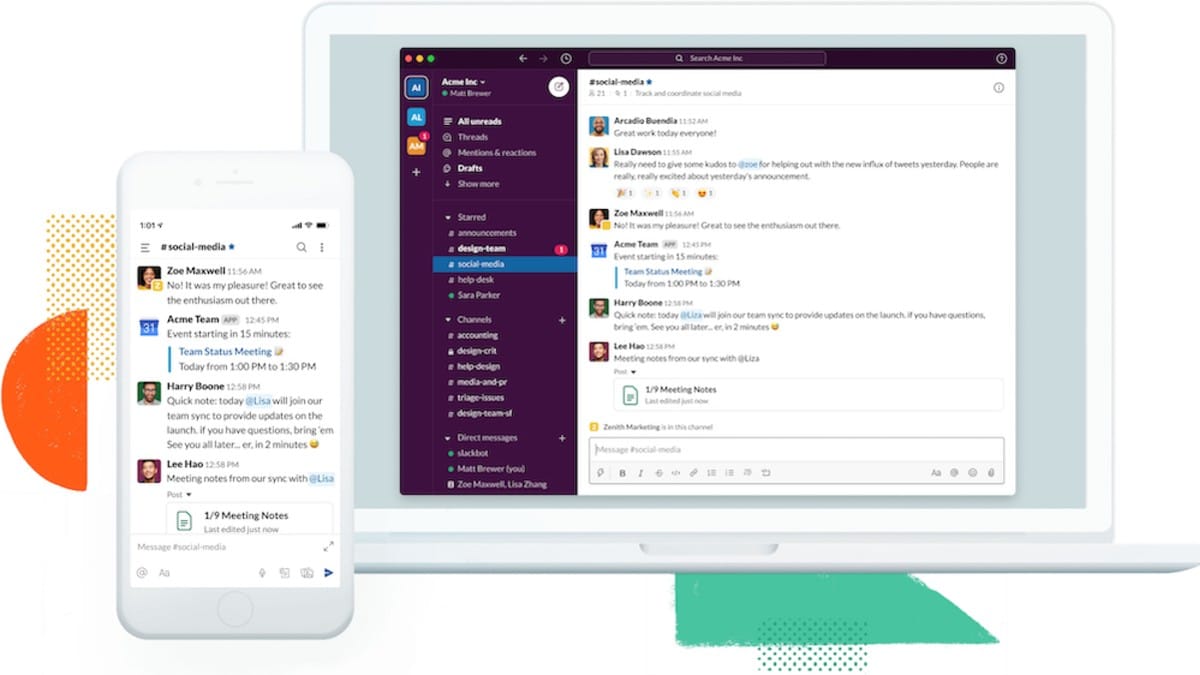

An office management tool, different people will probably describe Slack a little differently, depending on what they primarily use it for. Slack itself simply describes its functionality as: ‘Where work happens’.

It is an integrated tool that allows one to chat, share files and notes, create virtual office spaces, set up work processes, different channels for different processes/departments/functions, and, as NYT employees showed, band together as a union to press companies for demand.

Although it has been around since 2013, it has only in recent years been gaining a certain notoriety — as a tool that has empowered lower-level employees at media houses to call out editorial decisions of senior employees. In an extreme case, such as the NYT‘s, it’s with drastic effect.

An article by Digiday noted how “black employees organised a response to the op-ed in Slack”, and pointed out that the chorus of “Running this puts Black @NYTimes staff in danger” began as a chat among 35 employees on a Slack group.

Bosses seem to listen when employees speak on Slack.

According to the Digiday report, on 6 June, NYT‘s Executive Editor Dean Baquet said, “While I don’t run Opinion, I’m the senior leader of the newsroom … I also believe that some of the points being raised in this channel do point to things the news side can do better. So I’m reading. Thank you.”

He was responding to criticism from employees on how the publication was covering matters of race. The comments had been posted on the company’s Slack channel. And so Baquet chose the same platform to respond.

While making workplaces more efficient is Slack’s primary USP, it has begun serving a more fundamental purpose — tilting the power balance in favour of employees, to the point that it’s helping them usher in systemic cultural changes apart from reorganising workflows.

Also read: Black Lives Matter isn’t just challenging racism, but also the ‘both side-ism’ of journalism

One platform to rule them all

A team led by Stewart Butterfield, currently serving as Slack’s CEO, designed Slack as a communication and collaboration tool for the workplace. Before this, Butterfield had co-founded Flickr, a popular photo sharing site.

Slack was listed on the New York Stock Exchange in 2019. Financial results for the company in the quarter ending April 2020 showed revenue of around $201.7 million and a net loss over $74 million.

When it arrived, Slack was a pioneer in the workplace collaboration tool sector — in the global market for “team collaborative applications”, it was worth $3.5 billion.

Today, it competes with products such as Microsoft’s Teams and Google’s G Suite.

About 12 million daily active users (DAU) login on to Slack as compared to Microsoft Team’s 13 million DAU, according to the Business Insider report.

But Brian Elliott, VP and general manager of Slack, dismisses the emphasis on DAUs. “…What, really, is their significance? In our book, the ‘U’ is what matters: Use! Engagement is what makes Slack work,” he reportedly said.

Elliott said users spend over nine hours per workday connected to Slack. A Business Insider report added that at least 70 per cent of Slack’s top 50 customers have access to Microsoft Teams but still pay extra to use Slack.

Part of the platform’s success is it’s easy-to-use interface. It also incorporated the emojis feature to make communicating more interesting. Teams on Slack can share files, set up private groups to discuss confidential projects, and create open ‘channels’ on which employees can communicate, making emails redundant. Other communication apps like Twitter can be integrated with the platform, so it cuts down the need for someone to navigate away from Slack.

Also read: The economics of news media and why it’s in deep crisis because of Covid-19

Slack brings more than one kind of office revolution

News companies were among the “early adopters” of Slack, said Digiday.

The application made it easier for media companies to churn out stories, manage workflows and communicate internally without emails, the report added.

Like NYT, other American news companies adopted Slack, such as Conde Nast and 21st Century Fox, BuzzFeed and Vox.

Similarly, NYT‘s employees unionising on the Slack wasn’t the only such instance.

Wall Street Journal‘s reporters and editors sent a letter to the publication’s Editor-in-chief Matt Murray asking for “more muscular reporting about race and social inequities” after a discussion that took place on Slack in June.

At HuffPost, employee union representatives reached out to workers through Slack while negotiating with management for a new contract, Digiday reported.

In 2019, managers at Thrilist, a unit of the digital media startup Group Nine Media, locked writers out of a Slack channel during a stand off between managers and unionised employees.

The year before, Vox Media employees stopped using Slack to show they were serious about wanting management to recognise the editorial union.

Slack also encouraged some internal political activism when in 2017, Comcast employees used it to organise a protest against US President Donald Trump’s executive order temporarily banning immigrants from seven Muslim majority countries and his call to build a US-Mexico border wall.

According to Lowell Peterson, executive director of the Writers Guild of America East, bosses can’t do much when employees unionise themselves to seek demands because the conversation is taking place on the company’s Slack channel itself.

The conversation is openly taking place on a platform where the bosses are present, making any kind of retaliation for organising obvious, and so giving employees protection from any negative blowback, said Peterson according to Digiday.

Also read: WFH is giving the world economy a sneak peek at our digital, virtual future

Not all dandy

Within Slack itself, there are problems too. In June 2020, Vice reported how the company deleted a blog post on how Slack was working with police and had shared information. The post was deleted as protests against the killing of black American George Floyd by white policemen spread. However, black employees at the company said they had flagged the issue “years ago”.

In 2018, Slack’s updated privacy policy allowed administrators of a channel, which was typically your boss/higher up, to access private messages sent between employees without notifying them.

Other issues that have cropped up are how the platform has been extending work hours and reducing productivity. A 2017 nymag.com article cited Ali Rayl, Slack’s customer experience director, as saying that the platform had heard from “frustrated” upper management of firms about the number of Giphys employees were sending back and forth.

The same article further indicated that the platform also enabled office gossip. For “anyone who knew where to look”, gossip became searchable on Slack.

Also read: Why the era of free news for Facebook and Google may soon be over

The NYTimes revolution story could have been made better with Bari Weiss’ mention of her being harassed on Slack channels with an Ax in front of her name.. Good article otherwise