Beijing: On Jan. 15, it seemed like the U.S. and China had avoided a quick descent into a new Cold War.

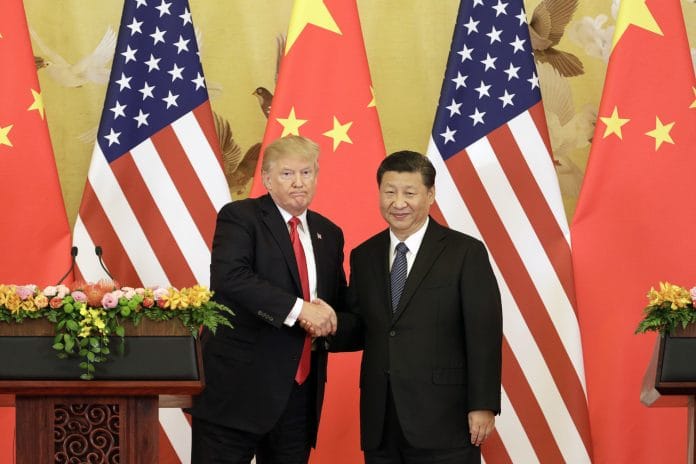

In Washington, U.S. President Donald Trump declared that “our relationship with China is the best it’s ever been” while signing a preliminary trade deal that “unifies the countries.” The pact between Trump and China’s Xi Jinping raised hopes that the world’s predominant superpower could peacefully resolve differences with a rising China.

That same day, health officials in the central Chinese city of Wuhan acknowledged that they couldn’t rule out human-to-human transmission of a mysterious new pneumonia that had already sickened 41 people. A man who had visited Wuhan also arrived home in Washington state carrying the deadly pathogen — the first confirmed U.S. case of the disease that would become known as Covid-19.

Four months later, the virus has prompted the worst global health crisis in at least a century, killing almost 300,000 people and plunging the global economy into a deep recession. The pandemic has also revived all the worst-case scenarios about U.S.-China ties, edging them closer to confrontation than at any point since the two sides established relations four decades ago.

From supply chains and visas to cyberspace and Taiwan, the world’s two largest economies are escalating disputes across several fronts that never really fell silent. Trump is even expressing frustration with the trade pact, one of few commitments preventing the rhetorical fights from spilling into the real world. On Thursday, Trump said he doesn’t want to speak with Xi and the U.S. would “save $500 billion” if it cut off ties with China.

The feud will likely get noisier before the U.S. election in November: Trump is increasingly blaming China for the virus turmoil as it undermines his chances at victory, while presumptive Democratic nominee Joe Biden, Congress and several states also join in. Meanwhile, Xi’s government has unleashed nationalist forces against the U.S. as slowing exports and rising joblessness push the country toward its worst downturn in generations.

“The Covid-19 attacks on both China and the U.S. seem to have pushed the deterioration of bilateral relations to the breaking point,” said Gao Zhikai, a onetime interpreter for late paramount leader Deng Xiaoping. “Never since the normalization of relations in 1979 have China-U.S. relations been as dangerous and as confrontational as today.”

While the trade pact for now lowers the risk of new tariffs, most other disputes between the two sides are the same or worse as during the depths of the conflict a year ago. Trump and his top aides have infuriated China with a daily barrage of criticism, including unsubstantiated claims that the virus escaped from a Wuhan lab, that Beijing is hording medical supplies and that the country’s hackers are probing U.S. organizations for vaccine research.

At the same time, Chinese diplomats and state media outlets have promoted conspiracy theories that U.S. Army athletes introduced the virus to Wuhan and accused “certain U.S. politicians” of trying to shift the blame for the world’s biggest coronavirus case tally. They’ve denounced Trump administration officials as liars, even calling Secretary of State Michael Pompeo “evil” on an evening news program.

Also read: How second Covid waves are hurting recovery in China, South Korea and Hong Kong

‘Act of War’

The crisis has prompted hawks on both sides to throw around threats that would’ve rarely been taken seriously during the decades when most in Washington advocated engagement with Beijing. Key Republican lawmakers have proposed canceling more than $1 trillion in U.S. debt held by China — a move Gao compared to an “act of war” — while the chief editor of a Communist Party newspaper suggested more than tripling the country’s relatively small stockpile of about 300 nuclear warheads.

The pandemic has also sparked tensions in old disputes, such as the status of democratically run Taiwan, which China has blocked from participating in World Health Organization events. Last month, the top U.S. health official held a rare phone call with his Taiwanese counterpart, and this week the U.S. Senate passed legislation seeking the island’s inclusion in WHO meetings while an American destroyer sailed through the Taiwan Strait.

The flow of information between the two countries has perhaps suffered the most immediate impact, with dozens of journalists expelled from both countries in recent months. Beijing warned of further retaliation this week after the U.S. reduced visas for Chinese media staff to 90 days.

Biden Detente?

The conflict has led some Chinese insiders to play down the prospects of another deal with Trump, who many in Beijing once viewed with relief as a pragmatist who wouldn’t be too concerned about human rights. Shi Yinhong, an adviser to China’s cabinet and an international relations professor at Renmin University in Beijing, argued in a recent speech that the country should tone down the rhetoric in the hopes of preserving a post-election relationship with the Democrats, who are emphasizing Trump’s responsibility for the outbreak.

“A Biden presidency will be less ideological and more practical,” said Susan Shirk, the chair of the University of California San Diego’s 21st Century China Center and author of “China: Fragile Superpower.” “Instead of confronting China across the board with the goal being unclear, a Biden administration will impose pressure in some areas, and remain tough in others — like national security and technology — with the goal being to negotiate changes in Chinese policies.”

Much depends on whether Trump’s “phase one” trade deal with Xi holds through Election Day. The president has shown increasing impatience with China, with S&P Global Ratings predicting that the country was unlikely to meet pledges to buy an additional $200 billion of American products this year and next year.

Trump and Xi probably have less appetite for a tariff war as the pandemic pushes their economies into historic crises. Among the biggest threat to both leaders is a sustained rise in joblessness that could prompt political unrest. More than 84,000 people have died from the coronavirus in the U.S., making it the worst-hit country in the world.

James Green, a senior adviser for geopolitical consulting firm McLarty Associates, pointed to a phone call earlier this month between top American and Chinese trade negotiators as evidence that both sides want to preserve the deal. China on Friday started allowing imports of U.S. farm products from barley to blueberries under the phase-one deal.

“You will see increased volatility in U.S.-China relations, with both sides playing to domestic audiences,” said Green, who was previously a U.S. trade official in Beijing. “That said, in my view there are signs that a working relationship can be maintained.”

‘Worst State in Decades’

Still, each new battle only deepens the suspicion between the two powers. The U.S. has used the supply chain disruptions caused by the virus to accelerate the push to move American production out for the country. In Washington, calls are rising to rescind Hong Kong’s special trading status as Beijing seeks to suppress calls for greater democracy.

On Thursday morning, Trump said he is “looking at” Chinese companies that trade on the NYSE and Nasdaq exchanges but do not follow U.S. accounting rules. The Federal Retirement Thrift Investment Board, which oversees a retirement-savings plan for federal workers, delayed a move that would’ve allocated billions of dollars to invest in Chinese companies. Later on Thursday, the Senate gave unanimous consent to legislation that would impose sanctions on Chinese officials over human rights abuses against Muslim minorities.

Shi, the Renmin University professor, said that efforts to decouple the world’s two largest economies appeared “much broader and much less selective” than before, with both sides “prioritizing their domestic issues.”

“China-U.S. relations have descended to the worst state in decades and will only get more tense,” he told Bloomberg News. “So the strategic confrontation will retrench, but the political and ideological tensions are being deliberately heated up.”-Bloomberg

Also read: Trump says he doesn’t want to talk to Xi as coronavirus tensions with China rise