New Delhi: Historic peace talks between the Taliban and the Afghan government began in Doha, Qatar, Saturday, witnessed by some of the most powerful people in the world and aimed at the Taliban sharing power in Kabul, even as the US exits from its longest war abroad.

The Taliban delegation walked into the venue — without masks and without women. The Afghan delegation led by Abdullah Abdullah, head of its High Council for National Reconciliation, has three women.

As many as 20 world leaders were present in Doha, including US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, US special envoy to Afghanistan Zalmay Khalilzad, Russian special envoy to Afghanistan Zamir Kabulov, Qatar’s foreign minister Sheikh Mohammed bin Abdulrahman Al-Thani as the host and NATO commander in Afghanistan Scott Miller. As the negotiations pick up pace, Khalilzad, who is in Pakistan Monday, is scheduled to visit India Tuesday.

In his opening remarks, Abdullah Abdullah admitted that Afghanistan is joining the peace talks because “in war, there is no winner or loser… We are here to figure out a process that will close the door of war forever and open the door of coexistence and peaceful life for our citizens”.

Taliban deputy leader Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar, who was recently downgraded from his position as head of the negotiating team to the head of the Taliban office in Qatar, said the insurgents would participate in the talks with “full sincerity”.

India was represented by its joint secretary in the Afghanistan-Pakistan division, J.P. Singh, but External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar delivered an address over video, calling for an “Afghan-led, Afghan-owned and Afghan-controlled” peace process.

Talks between the Afghan delegation and the Taliban began immediately after the opening, in the backdrop of mounting Taliban attacks in 18 provinces inside Afghanistan — as many as 50 people have been dying every day in violence in recent weeks. The Taliban negotiating team is recast and far more hardline than before. It is led by Mawlawi Abdul Hakim Haqqani, a close aide of Taliban founder Mullah Omar, who has replaced the more moderate Mullah Baradar.

The Taliban delegation is packed with Mullah Omar aides as well as key members of the Haqqani Network, which has carried out terrorist attacks against India — Abdul Manan Omari is Mullah Omar’s brother; Noorullah Noori spent 12 years in Guantanamo; Mullah Shireen Akhund was responsible for security in Mullah Omar’s residence; Mullah Khairullah Khairkhaw was minister for interior during the Taliban regime and was also in Guantanamo; Shahabuddin Delawar was the ambassador to Pakistan during the Taliban regime and Anas Haqqani, only 26 years old and younger brother of Sirajuddin Haqqani, was released from prison last year in exchange for two kidnapped foreign professors at the American University in Kabul.

The Afghan government has already released 4,019 of the 5,000 prisoners it promised it would hand over when it signed the peace pact in February; the Taliban have released 737 prisoners so far. But with the US and France resisting the release of several hundred more demanded by the Taliban, a second list of 592 prisoners was handed over by the Taliban to Abdullah Abdullah’s team.

The US has also promised to withdraw 5,000 troops and shut down five bases within 135 days of the peace agreement. It’s not clear when the remaining 14,000 US troops will leave.

The peace talks were not without their fair share of irony. They took place one day after the 19th anniversary of the September 11 attacks that changed the world in 2001. Only three days earlier, on 9 September, a convoy of Afghanistan’s first vice-president and former intelligence chief Amrullah Saleh was attacked as it drove through Kabul. Saleh and his son, Ebadullah, who was also in the vehicle with him, escaped with minor burn injuries, but 10 bystanders were killed.

This was the second attack against Saleh, who has minced no words against the Pakistani state’s destabilisation of Afghanistan, in a year.

Last July, Saleh barely escaped with his life when terrorists stormed his four-storey office in Kabul with machine guns and explosives, killing security personnel and waiting visitors. The gun-battle that followed lasted more than 19 hours, an indication of the serious intent of the insurgents.

As Saleh’s security guards held them off, the vice-president raced to the roof and escaped via a ladder thrown across to the roof of the neighbouring building.

The attack against Saleh on 9 September is no coincidence. Exactly 19 years earlier in 2001, the great Afghan strategist and military genius Ahmad Shah Massoud was assassinated in his lair in the Panjshir mountains, a 100-odd km outside Kabul, by two Tunisian Al Qaeda fighters pretending to be journalists.

By the time Massoud was airlifted and brought to the hospital in Farkhor run by India just inside the Tajikistan border, he had died. He was 48 years old.

Abdullah Abdullah, a close confidante of Massoud, remembered his hero in his opening remarks in Doha Saturday: “I vividly remember when the late national hero, Ahmad Shah Massoud, unarmed and with one guard, met with Taliban leaders in Maidan Shahr in 1995, to seek a peaceful political resolution,” Abdullah said. “Alas, we failed to reach a peaceful agreement because of circumstances beyond our control at that time.”

Also read: Here’s what China is doing in Bangladesh, Nepal, Afghanistan. It doesn’t look good for India

Massoud and the early attempt at reconciliation

What Abdullah did not mention was that Massoud, by early 1995, had initiated a national reconciliation process to bring all the warring parties on board, including the Pakistan-backed Gulbuddin Hekmatyar and his Hizb-e-Islami, so as to stop a civil war.

Massoud had even reached out to the Taliban and went to meet them in Maidan Shahr, a city less than two hours away from Kabul that they controlled — alone and unarmed.

But the Taliban turned down his offer and Massoud returned to Kabul. Shortly after, the Taliban leader who had hosted him was killed by his own colleagues for failing to make use of the opportunity to assassinate Massoud.

In fact, Massoud had been trying to unify all the Afghan factions, within weeks of the last Red Army soldier walking back over the Amu Darya bridge in early 1989.

He had been at the forefront of the anti-Soviet jihad, his guerrilla tactics against the mighty Soviet army the stuff of legend. The “lion of Panjshir”, it was said, would lure the “Soviet bear” into his redoubt; they would walk right into the ambushes laid by Massoud’s men; when the Soviets withdrew, Massoud and his men occupied those areas.

The Afghan leader admitted he had learnt these tactics from reading Mao and Che Guevara.

In 1983, the Soviets offered a truce, which Massoud accepted, using it to regroup his forces. It is how he created the Shura-e-Nazar, uniting 130 commanders from 12 provinces to fight the Soviets. While the other “Peshawar parties” spent their time on internecine rivalries in Pakistan next door, Massoud became the backbone of the mujahideen, putting the fear of Allah into the godless Communists.

When the Red Army finally left Afghanistan in 1989 after a full decade, beaten and bowed — the Soviet Union would break up only two years later, its general secretary Mikhail Gorbachev calling it a “bleeding wound” — Massoud once again tried to regroup the disparate commanders.

The Pakistan hand in Talibani rise

In April 1992, the UN agreed that a government should be formed in Kabul with elite consensus — only Hekmatyar, backed by the Pakistanis, stood outside the tent. But Hekmatyar refused Massoud’s invite to join, saying “We will march into Kabul with our naked sword…”

Around this time, according to Peter Bergen, writing in The Osama bin Laden I know, bin Laden told Hekmatyar to join ranks with his “Islamic brothers,” although he “hated Massoud”. But Hekmatyar refused, saying he was confident of gaining power in Afghanistan of his own accord.

But the Pakistanis soon dumped Hekmatyar and began to train, fund and support a new movement of young Pashtuns from southern Afghanistan. The Taliban would take Kabul on September 27, 1996, and establish the cruellest regime seen anywhere in contemporary times. Only three countries in the world supported the Taliban — Pakistan, the UAE and Saudi Arabia.

‘The Taliban File’ sourcebook at George Washington University later described the situation as follows: “Initially, the Pakistanis supported … Gulbuddin Hekmatyar … When Hekmatyar failed to deliver for Pakistan, the administration began to support a new movement of religious students known as the Taliban.”

According to Neamotullah Nojumi in The Rise of the Taliban in Afghanistan, Hekmatyar was receiving operational, financial and military support from neighbouring Pakistan. Amin Saikal of Australian Western National University said Pakistan wanted to establish a favourable government in Kabul because it wanted easy access to Central Asia’s rich resources.

Five years later, and two days before the 9/11 attacks, Massoud was dead. His opponents had finally got him — the Al Qaeda’s ‘Tunisian journalists’ only pulled the trigger.

Born a Tajik, Massoud had done more in his short lifetime to try and unite Afghanistan’s very diverse and tribal society riven across several traditional faultlines. Tajik vs Pashtun vs Hazara. Dari vs Pashto vs Farsi. Sunni vs Shia.

“Massoud was the greatest Afghan patriot. He emerged from the Soviet jihad to continue the resistance against the Taliban. He was briefly in Pakistan in the mid-1970s for some training, but unlike other Afghan resistance leaders he never lived there. He understood the nature of the Pakistani state,” Vivek Katju, a key diplomat on the Afghanistan-Pakistan desk in the Ministry of External Affairs, told ThePrint.

Katju had met Massoud several times.

“Mere months before his own death and the 9/11 attacks, he went to a conference in Brussels to tell the West that they had to be involved in Afghanistan beyond their interest in curbing Osama bin Laden,” Katju told ThePrint.

Also read: India took the high moral ground by not talking to Taliban and lost influence in Afghanistan

The Massoud shadow on a peace deal

As they dig into their negotiations with Abdullah Abdullah and his team, less than a fortnight from now, the Taliban will celebrate the day they took Kabul, on September 27, 1996.

They have bided their time these past 24 years, melting into the hills in the aftermath of the US invasion in November 2001, returning to the frontlines as the US began to get distracted by the Iraq war and started bleeding heavily in both theatres.

As a Taliban commander famously told former Canadian chief of defence staff Rick Hillier, soon after US & NATO forces began to gather in Afghanistan following 9/11, “You may have the watches, but we have the time.”

The toll in the 19-year-long war, longer even than the war the US fought in Vietnam, has been severe on all sides. The US lost more than 2,440 soldiers and has spent about $975 billion. More than 100,000 Afghans have been killed or wounded since 2009, when the UN Assistance Mission for Afghanistan started counting casualties.

The Taliban, meanwhile, are stronger than never before. They have 60,000 full-time fighters and are in control of one-fifth of the country. Another half is contested. The Ashraf Ghani-led government controls what’s left.

Certainly, the elimination of Ahmad Shah Massoud in 2001 was a critical step in the Taliban’s journey back to Kabul in 2020. Massoud’s death splintered the Afghan opposition. There was no one person who could take charge and advise the Americans how to best use their resources.

Rakesh Sood, a former ambassador to Afghanistan, points out, “9/11 would have still taken place, but when the Americans moved in, given his stature and standing, they would have had to listen to Ahmad Shah Massoud. He would have led the fight against the Taliban. The history of Afghanistan would have been different.”

From 1996-2001, the US’ primary agenda was to support the Taliban in power so as to pave the way for economic development, for example the Unocal gas pipeline that several interested parties, including then US diplomat for South Asia Robin Raphel, was pushing for.

The Americans gave Massoud very little, just some satellite phones and other communication equipment so that he could help them find Osama bin Laden.

But by 2001, as noted US journalist Steve Coll said in his book, Ghost Wars, a shift in US policy was in the offing: “The CIA officers admired Massoud greatly. They saw him as a Che Guevara figure, a great actor on history’s stage. Massoud was a poet, a military genius, a religious man, and a leader of enormous courage who defied death and accepted its inevitability, they thought. … In his house there were thousands of books: Persian poetry, histories of the Afghan war in multiple languages, biographies of other military and guerilla leaders.

“In their meetings Massoud wove sophisticated, measured references to Afghan history and global politics into his arguments,” Coll wrote. “He was quiet, forceful, reserved, and full of dignity, but also light in spirit. The CIA team had gone into the Panjshir as unabashed admirers of Massoud. Now their convictions deepened.”

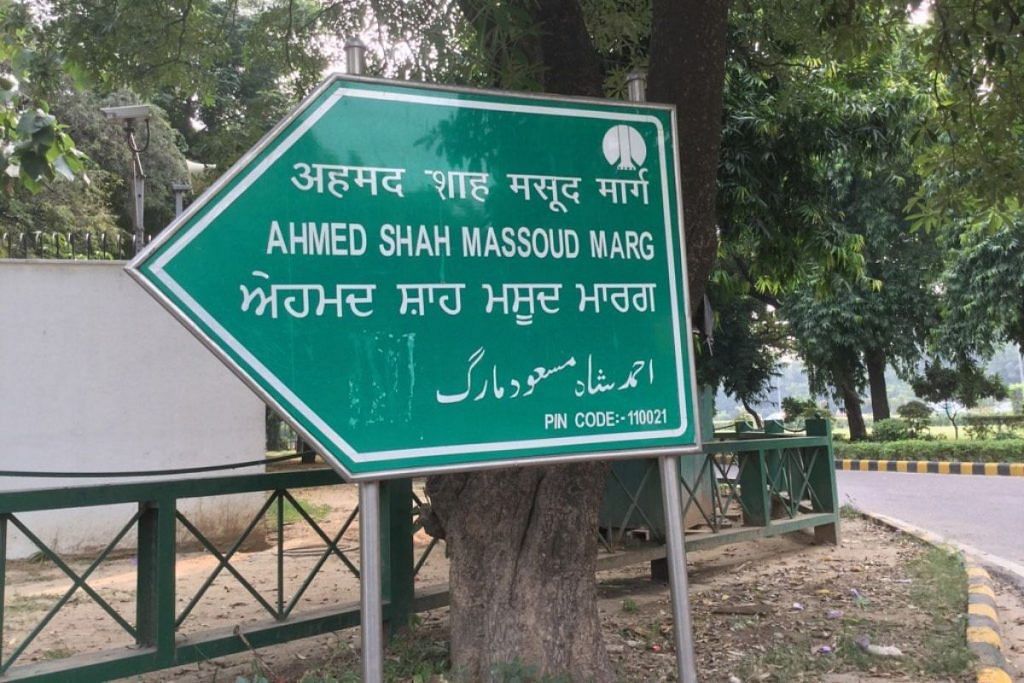

The 9/11 attacks all but consumed Massoud’s legacy, but in a small corner of Delhi, India mourned his death and remembered the doughty Afghan fighter.

A street in the capital’s Chanakyapuri was named after him, in silent recognition of a not insignificant chapter in India’s diplomatic history when India, along with Iran and Russia, sent Massoud some military hardware, weaponry and two or three fighter jets. According to one estimate, the aid amounted to a mere $70 million — but at least someone was helping.

The Indian operation began sometime in the spring of 1996, just before the Taliban took Kabul, forcing Massoud to flee to the Panjshir Valley. For the next five years, a variety of Indian diplomats would be in touch with the Northern Alliance leader, as they made the difficult journey from Delhi to the Tajik capital, Dushanbe, then took a rickety plane from the border to the Panjshir valley.

Vivek Katju, later India’s ambassador to Afghanistan, was on that plane more often than not. He met Massoud scores of times. India’s ambassador to Tajikistan, B.R. Muthu Kumar, ran the operation for some time from Dushanbe. Jayant Prasad, who happened to travel to Dushanbe once to check out the logistics needed to set up the Farkhor hospital, tells the story of the pilot who would test the quality of petrol in the plane he was to fly to the Panjshir by swirling it in his mouth.

“Massoud was a truly modern leader who never let a foreign power dictate to him even when he was taking their help. But look at the way the cookie has crumbled,” Katju said. “The day the Americans refused to clean up the Taliban sanctuaries in Afghanistan – understandably so, because Pakistan is a nuclear weapons power – Kabul ceased to be fully coherent.

“Today, the Taliban are so powerful that they are negotiating a return to power-sharing in Kabul,” Katju added.

Certainly, India is keeping an eye on the progress of the intra-Afghan negotiations, expected to last several weeks. But back in Afghanistan, the question on the mind of every Afghan is whether Taliban 2.0 will be a reincarnation of its earlier avatar — and whether women will once again be subject to oppression and exclusion or retain their place in the frontlines.

Taliban officials say that some of the old rigidities need reforming, but are not prepared to say which ones. In Helmand, a middle-aged woman told the well-known journalist Farahnaz Forohtan recently that she wants a peace that lasts. “I was once whipped in public (during the Taliban regime) for taking my sick child to the doctor,” she said, adding, “I don’t want a five-day peace.”

Activist and former parliamentarian Fawzia Koofi, who survived an assassination attempt barely two weeks ago, is part of the Afghan delegation in Doha. “Historic day for Afghanistan. No war can end with war…” she tweeted.

Historic day for Afg.

No war can end with war.People who lost lives during +40yrs are not just figures.Many opportunities,talents and dreams for a better life were buried with them.We continue to suffer.Time to act as responsible citizens and put a dignified end to this bloodshed pic.twitter.com/0uXnHB7Dwp

— Fawzia Koofi (@FawziaKoofi77) September 12, 2020