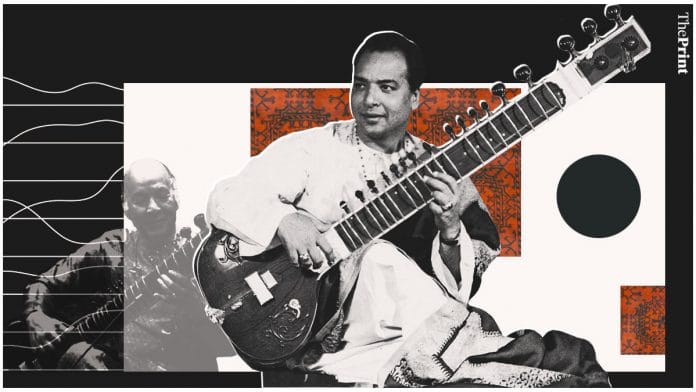

While watching a video of a joint concert with Ustad Bismillah Khan, one notices that sitarist Ustad Vilayat Khan has an unassuming aura while playing. The instrument seems like it is an extension of his body and Khan is so immersed in his performance that it is almost as though he is unaware of his own musical brilliance and captive audience.

If one didn’t know, one might not think that Ustad Vilayat Khan comes from a long lineage of sitarists. Born in Gouripur in East Bengal, now in Bangladesh, on 28 August 1928, Khan along with his father, grandfather and brother, are widely credited with developing the gayaki ang of sitar playing. His grandfather Imdad Khan was such a highly regarded sitarist that the Etawah gharana was renamed Imdadkhani gharana.

Vilayat Khan was just eight years old when he made his first recording for the Megaphone Company. Two years later his father (and his guru) passed away, an immense loss, he noted in an interview with Karan Thapar. After that it was his mother, Bashiran Begum, uncles Wahid Khan and Zindo Hussain Khan and grandfather Bande Hussain Khan who trained him in sitar. At this time, Khan said, that he used to train for anywhere between 8-14 hours a day.

His prowess was revolutionary within the music world as Khan introduced the left-hand technique of playing the sitar, which enabled the continuity of note for a longer duration and also introduced the highly intricate and difficult khayal ang murki-s, evolving a fluid music.

Aside from his own musical genius, he was a man with firm views and a clear idea of how he wanted to live life. In the same interview with Thapar, Khan said, “I don’t want to be a president or any pop star, I want to be in my own shell. Yet I want to know that in my own shell, I am the pearl. Whoever wants to know me will open the shell.”

On his 15th death anniversary, ThePrint speaks to his disciple Dharambir Singh to understand the life, legacy and motivations of this fascinating genius.

Lessons from Ustad

Dharambir Singh was only 16 years old when he made the move from Amritsar to Dehradun to learn how to play the sitar from Ustad Vilayat Khan. It was 1976 and Khan lived in Clement Town in Dehradun. Singh shifted his school and rented a room, all to learn the sitar from Khan, which he did until he was 21.

Singh tells ThePrint that in those five years, he learnt the world. He recalls that Khan’s voice was so powerful that when he went on to stage, he was king.

“The quality of music we heard was all part of our training. Even today, when we are practising, our brain is programmed to that noise and we know that we are nowhere close to that.”

However, a memory that stands out for Singh is one which highlighted Khan’s dedication and commitment to his riyaz.

“It was sometime either in 1976 or 1977 when Ustadji got a telephone call from the office of Indira Gandhi. His young daughter Zila picked up the phone and said that she could not give the phone to her father as he was doing his riyaz. I was astonished — it was after all the prime minister of the country. Later that day, I asked Ustadji why he did not take the call from such an important person, and he told me, ‘The sitar is my companion for life. Indira Gandhi will come and go but my relationship with the sitar is forever’.”

Also read: Pandit Ravi Shankar — the sitar maestro who introduced ragas to the West

Rivalry with Ravi Shankar

In her book, The Sixth String of Vilayat Khan, author Namita Devidayal writes, “Vilayat Khan did not merely play his sitar. He sang through it. It was this distinctive quality that made him, arguably, a finer player than his lifelong adversary — Pandit Ravi Shankar.” She says that despite coming from different worlds, the two things the musicians had in common was their mastery over their instrument and unabashed self-absorption.

There were two major streams of the sitar, the Maihar gharana, which Ravi Shankar represented, and the Etawah or Imdadkhani gharana, the lineage which Khan came from. But their approach to music and, in fact, life, was also different.

An oft-told story about their rivalry is related to a concert in 1952, called the Jhankar concert. According to Devidayal’s book, Khan “stormed in to play with Ravi Shankar, pushing their relationship to a point from which there was no going back. And it was there that he was declared the de facto victor in the battle of the sitars”.

Although he pretended not to care about awards and recognition, this wasn’t strictly true. Devidayal writes, “It’s not as if Khansahib did not care. He did. Sometimes he checked how much Ravi Shankar was getting from concert organisers and asked for just a little more. But the rivalry was dramatised by their students and the buzzing bees of the music world rather than the two artistes themselves. Both probably knew deep within that comparison and competition in music was as pointless as comparing two stars in the Milky Way.”

Singh echoes the sentiment by stating that it was their fans who created much of the drama and comparison between them. He recalls that Khan told him that he had deep respect and love for Ravi Shankar and remembered the time when he was invited to his (Shankar’s) house in Varanasi, and how well he was taken care of.

Devidayal also notes, “He (Khan) served as a reminder that there are spaces more intoxicating than fame. As Hans Utter wrote, compared to Ravi Shankar, Vilayat Khan made his life and art ‘a narrative of resistance’.”

Refusing awards

These days, returning awards is often viewed as a political act. But Khan, who was awarded a Padma Shri and Padma Bhushan in 1964 and 1968 respectively, refused to accept them for rather different reasons.

He declared that the committee was musically incompetent to judge him, and did not want to accept any award that another musician whom he considered inferior, had received before him.

He refused a Padma Vibhushan in 2000 as well as the Sangeet Natak Akademi.

Singh says Khan questioned the entire selection criteria when in one of the awards, Annapurna Devi (Ravi Shankar’s former wife) got an award before him, which upset him. “Therefore he did not take these awards seriously.”

The only titles he accepted were the special decorations of “Bharat Sitar Samrat” by the Artistes Association of India and “Aftab-e-Sitar” (Sun of the Sitar) from President Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed.

He also famously boycotted All India Radio. Singh explains how when the musicians union and radio union were paid very little, Khan organised a strike with them to protest against this. “He was a fighter and had a strong personality and therefore fought alongside them.”

However, when he met the then broadcasting minister — Morarji Desai — Khan was put down and not spoken to properly. It was also at that point that many musicians of the union defected. “Ustadji was very hurt and after that he took a vow that he would not play for radio.”

Ustaads parting words

Towards the end of his life, Singh visited Khan at his home in Kolkata. He tells ThePrint what the maestro said to him: “I want you to remember that the sitar is always in front of you and you are behind it.”

“It is such a beautiful thing to remember,” Singh notes. “In our world today, Ustadji‘s teachings are still relevant as he said that publicity and wealth is all a gift, but it is not the main aim. Music is.”

Also read: How as a young boy, Hariprasad Chaurasia came to choose music over wrestling, flute over sitar

Great article on Ustad ji. Thanks Revathi