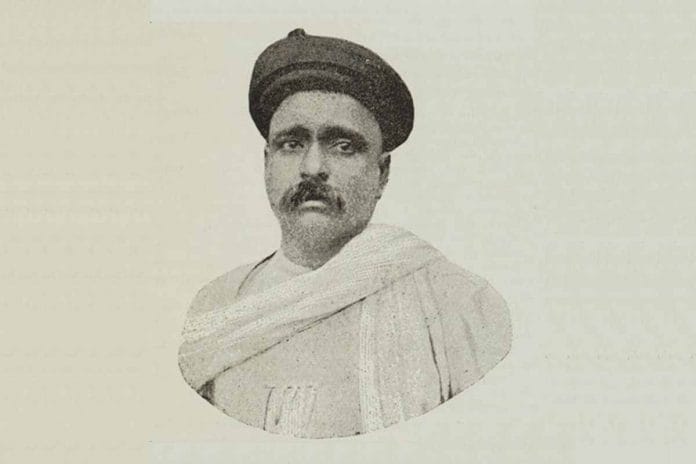

India is still debating sedition 150 years after its entry into the lawbook. But we have overlooked the peculiar trial of Bal Gangadhar Tilak. Let’s revisit the nationalist leader’s arguments against sedition.

Tilak has been called an ‘extremist’ — a class apart from the ‘liberal’ moderates whom the British empire found easy to liaise with. During the end of the 19th century, Tilak spearheaded a revolution when dissent against the British was picking up in its most direct form. The feisty Indian politician was instrumental in arousing a dormant nation to the nationalist cause and making it aware of its political plight under foreign rule. “Swaraj is my birthright and I shall have it” — Tilak boldly declared, marking the beginning of radical nationalism.

A strong proponent of Swaraj, Tilak wrote in his Marathi newspaper Kesari, “We will get nothing by appealing to or shouting hoarse in the ears of the British bureaucracy in India. It is like breaking our heads against a stone wall.” His articles drew a lot of flak from the colonial government, which arrested and tried him for sedition on three occasions. At the time, the concept of ‘seditious offence’ was relatively new for Indians, with explicit, full-scale defiance against the British yet to come.

Even after Independence, Parliament debated the validity and need for such a law, which was described by Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru as “highly objectionable and obnoxious”.

The crushing of dissent

Tilak’s 1897 sedition trial sent shockwaves in India. The law, enshrined in Section 124A of the Indian Penal Code, was introduced by the British in 1870 when it saw the first signs of dissent in India. Its catchword was ‘disaffection’, referring to inciting sentiments against the State.

The British government claimed that two of Tilak’s texts in Kesari — referring to Shivaji’s killing of Afzal Khan — incited seditious and anti-national feelings, and inspired the assassination of British civil service officer Walter Charles Rand and his military escort Lieutenant Ayerst. The trial marked the beginning of the criminalisation of dissent.

It’s important to note that sedition became a part of the IPC only when dissenting voices against the Raj grew — the British State realised it needed a ‘fix’. Tilak’s voice was the loudest.

1897 marked India’s descent into a nation that departed from the idea of free speech. It viewed even discursive violence as a criminal act. Tilak was sentenced to a year in prison. In 1908, he was once again tried for sedition when two European women were killed by Khudiram Bose and Prafulla Chaki. The British accused Tilak of conspiring with the ‘militants’ and trying to disgrace the imperial crown, triggering feelings of ‘disaffection’.

Also read: Gopal Ganesh Agarkar is Maharashtra’s forgotten ‘apostle of rationalism’. Look beyond Tilak

Demanding the ‘birthright’

Tilak was at the forefront of leading popular agitations against the British. One of them was the Swadeshi movement. Its suppression by the British led to a violent backlash from the masses. Tilak stressed that the demand for Swaraj was amplifying, and the government could no longer ignore it.

In its effort to nip the Swadeshi movement in the bud, the British passed the Prevention of Seditious Meetings Act in 1907. Public meetings and large gatherings were banned. The law was enforced in view of a larger movement unfolding in the United States, the Ghadar movement, which the British believed was encouraging violence. The following year, the Explosive Substances Act was passed. “These measures are unsustainable. The British have entered a new policy of repression,” Tilak wrote in Kesari.

In 1908, the British government also enacted the Newspapers (Incitement to Offences) Act, which enabled district magistrates to confiscate printing presses if they published ‘seditious’ material. “Liberty of speech and liberty of the press give birth to a nation and nourish it,” Tilak wrote.

‘Father of Indian unrest’

Throughout his prolific political career, Bal Gangadhar Tilak questioned sedition and challenged the very premise of the draconian law that is still used to incarcerate dissenters. In 1908, despite lawyer Muhammad Ali Jinnah’s strong defence, Tilak’s bail was rejected in court. So Tilak decided to fight the case on his own.

Tilak tackled the British jury by questioning its understanding of what Kesari published — after all, the British weren’t the magazine’s intended readers. Kesari was for Marathi speakers. As far as insinuation and intentions were concerned, Tilak argued that the issue arose from translation. In Marathi Kesari, there were no terms inciting violence or instigating citizens.

Tilak’s argument fell on deaf ears, and he was still convicted and sentenced to six years in prison. But that didn’t deter him from re-joining the national movement with gusto upon release. Before M.K. Gandhi gained prominence in the freedom struggle, Tilak had shaped the national movement and nourished the dream of Swaraj.

The National Crime Records Bureau data showed a 165 per cent jump in sedition cases between 2016 and 2019. Dissent is not a crime, and as George Orwell said, “If liberty means anything at all, it means the right to tell people what they don’t want to hear.”

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)