The doctor stared aghast at the condition of the girl lying on the hospital bed. She had delivered a child a week ago, and had just been brought in as she could control neither urination nor defecation. On examining her, the doctor discovered a large hole in the anterior wall of the bladder, a torn rectum, a broken pelvic joint, and separated pelvic bones. His urgent questions to her relatives revealed a horrifying story.

The ordeal started when the girl went into labour and the baby was found to be in a transverse position with the arm prolapsed. The midwife made her sit on two stools and fomented the area with red hot charcoals placed beneath. Then she tried to deliver the baby by pulling with all her might at the prolapsed arm. Eventually, the baby was delivered dead and the mother was left with horrific injuries.

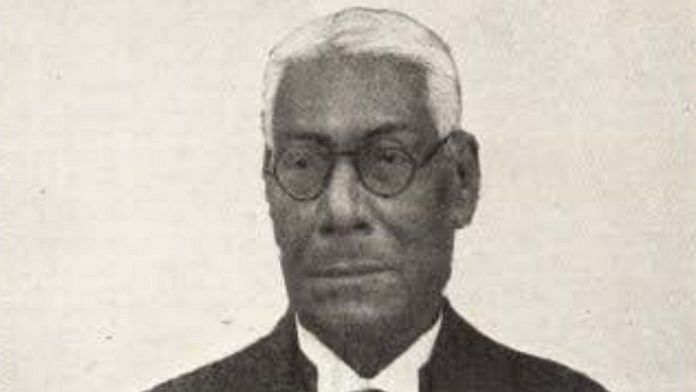

The year was 1912 and such appalling scenes were by no means unusual. It was this grim reality that spurred Dr Kedarnath Das, a leading obstetrician and gynaecologist in Calcutta (now Kolkata), to create specially designed forceps for Indian women in 1913. These instruments, called ‘Das forceps’ after him and still in use today, made deliveries safer and less painful, while also helping prevent many infant and maternal deaths. Dr Das’ contributions to his field, from the forceps to the books he authored, earned him acclaim not just in India but abroad as well.

Innovator & author with an Indian focus

Born on 20 February 1867 into an educated family of modest means, Das was a stellar student who won many medals and scholarships through school and college. He distinguished himself at Calcutta’s Medical College, emerging as the ‘best student of the year’ in 1892. After topping the University of Calcutta examinations the same year, he went on to obtain an MD in Gynaecology and Obstetrics from Madras University in 1895.

Das’ reputation as an outstanding gynaecologist and obstetrician stemmed from his long practice at Campbell Medical School (now Nil Ratan Sircar Medical College and Hospital, Kolkata). In 1919, he took charge of the Department of Gynaecology and Obstetrics at Carmichael Medical College (now RG Kar Medical College and Hospital, Kolkata), going on to serve as its principal from 1922 until his death in 1936.

But Das’ most significant contribution to the medical field was the forceps that he designed. These were shorter, more delicately made, and better suited to young Indian mothers of the time. Child marriage, the norm in India back then, meant that expectant mothers were often teenagers, some as young as 12 or 13, with the pelvis yet to develop fully. Additionally, newborns tended to be of lower birth weight. The ordinary forceps then in use had been designed for the adult Western woman. These were far too big for the narrow pelvis of the young Indian mother and caused distress and damage to both mother and infant.

In 1928, Das achieved another milestone by becoming the first Indian to publish a book on Obstetrics for students and interns, titled Obstetric Forceps: Its History and Evolution.

This was a vital contribution as it was written with the Indian context in mind, incorporating facts and perspectives either ignored or cursorily mentioned in Western textbooks. For this work, Das invested 12 years in collecting and distilling knowledge from books published in multiple languages around the world. He also delved deep into ancient Indian medical knowledge, tracing the use of forceps back to Indiain 1500 BCE, through Hippocrates in 5th century BCE Greece, and Avicenna or Ibn Sina in 10th century CE Southern Central Asia, up to modern times.

Forcefully repudiating the assumption that surgery originated in the West, he wrote: “One may reasonably observe that Indian medicine was in possession of an imposing treasure of empirical knowledge and technical achievement… surgery constituted the summit of attainment of Indian medicine and Hindu practitioners were accustomed to perform difficult operations with boldness and skill.”

The book was an instant success and was reviewed by every significant journal in the field. Moreover, it made experts sit up and take note that a scholarly medical text from India could rival the best of the West.

As one Western reviewer reportedly wrote in the Journal of Surgery, Obstetrics and Gynaecology: “Only the title page with its dedication to the use of students in the medical schools and colleges in India denotes the exotic character of the book… We would do well to relegate Rudyard Kipling’s phrase of ‘the white man’s burden’ to the realm of jingoistic propaganda.”

Also Read: Child bride to doctor—Bengal’s Haimabati Sen traded her gold medals for a monthly stipend

A voice for Indian medicos

Das was a vocal opponent of any discrimination meted out to Indian medical practitioners. In 1913, the Islington Commission invited responses to a questionnaire on recruitment for public services. To this, several British members of the Indian Medical Service gave statements opposing simultaneous examinations being held in England and India— which would have benefitted Indian medical aspirants. They argued that training in midwifery was not up to the mark in India.

Das reacted immediately with a strongly worded memorandum detailing the high standards adhered to in Indian universities, particularly in the medical colleges affiliated with the University of Calcutta, effectively silencing those who had raised this apprehension.

The greatest irony here was that most Indian medical colleges were headed by European members of the Indian Medical Service — hence the fault, if any, rested with them.

Making a difference in women’s lives

While Dr Kedarnath Das’s achievements are impressive, we must not overlook the bedrock of his contributions—the compassionate care he provided at the bedsides of women during labour and childbirth.

Traditional ideas of purity and pollution meant that the room allotted for delivery was one of the worst in the house—dark, damp, and often infested with vermin. The men of the house rarely concerned themselves with the event or the risks it entailed. The expectant mother, often just a teenager, was usually left at the mercy of the dai (midwife). In the absence of modern hygiene practices, septicemia (blood poisoning) resulting in an agonising death, was frighteningly common. Because of rigid social norms, most families strongly resisted the idea of a hospital delivery in the presence of a male obstetrician.

Battling persistently against these obstacles, Dr Das persuaded many families to revise their views and seek medical help in hospitals. He was known to sit for hours by the bedside of the woman in labour, waiting patiently for nature to take its course. He would not leave until he was certain that both mother and child were doing well. This, of course, entailed substantial sacrifices where rest, leisure, and social engagements were concerned.

Dr Kedarnath Das’ work received ample recognition in India and abroad. He was named an Honorary Fellow of the American Gynecological Society and the American Association of Obstetricians, Gynecologists and Abdominal Surgeons. When the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists was founded in Britain in 1930, he was elected as a Foundation Fellow. He received the Companion of the Order of the Indian Empire in 1918 and was knighted in 1933. However, it is from the women of Bengal that he received the highest respect and gratitude. While his pioneering work may have faded from public memory, its positive impact endures.

Dr Krishnokoli Hazra teaches History at the undergraduate level in Kolkata.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)