On 18 April 1859, the day of his execution, Tatya Tope wanted to wear a white kurta pyjama and meet his fellow freedom fighters. The authorities refused his request. But finally, they relented on one point and allowed one of the key leaders of the 1857 revolt to choose his clothes for his hanging.

He climbed the scaffold erected on a field in Sipri (now Shivpuri), and walked toward the gallows. “Bharat Mata ki Jai,” he shouted, after the hangman placed the noose around his neck and before the trap door opened.

At least, that was the popular narrative.

Until his descendant, Parag Tope, a software engineer in the United States, questioned it in his book, Tatya Tope’s Operation Red Lotus.

The many theories around Tatya Tope

More than 150 years after the execution of Tope, Parag claimed that the man who was handed over to the British and hanged in his stead was Raja Man Singh of Narwar. History remembers Man Singh as the man who betrayed Tatya Tope.

In his book, Parag cites letters exchanged by British officers, which suggest that Tope was still active under different names, such as Ram Singh, Jeel Singh, and Rao Singh, long after his supposed hanging.

Another theory is that the leader of the 1857 revolt had been killed on 1 January 1859 in a battle near Guna in Madhya Pradesh. This has reportedly been backed by the RSS-affiliated Akhil Bharatiya Itihas Sankalan Yojana (ABISY), which incidentally launched an ambitious project last year to bring out a “comprehensive history of the country” in eight volumes.

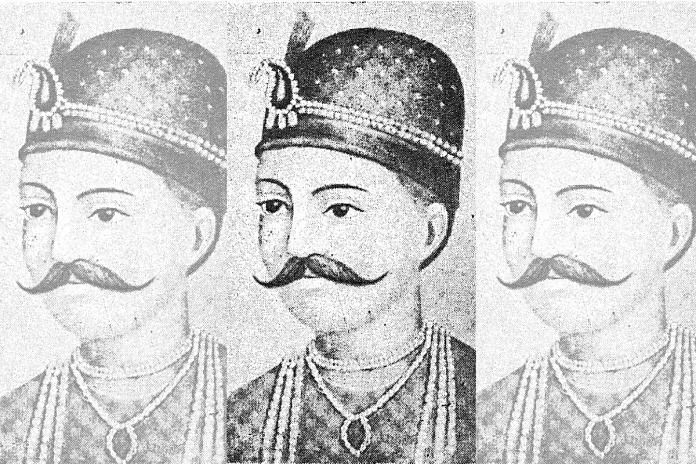

Against this backdrop, Tope’s story is incomplete. The fate of the commander-in-chief of Nana Saheb Peshwa II’s army and one of the key leaders behind the fall of Kanpur (then Cawnpore) in 1857, who later joined forces with Rani Lakshmibai of Jhansi to capture the Fort of Gwalior, is still being debated.

Also read:

Bound to Nana Saheb, guerilla master

Tatya Tope was born Ramachandra Panduranga into a Deshastha Brahmin family in Maharashtra’s Nashik. In 2020, the Indian government announced that a museum dedicated to Tope would be built in his hometown of Yewla.

He was bound to Nana Saheb Peshwa II by ties of loyalty and gratitude, wrote Sayed Jafar Mahmud in his book Pillars of Modern India, 1757-1947, and rose the ranks to become Tatya Tope.

By 27 June 1857, the revolt or First War of Independence had reached Kanpur, a garrison town for the East India Company armies. Then British General Hugh Wheeler, who was fluent in Hindi, had adopted local customs and married an Indian woman, was confident that the sepoys under him would not join the fight. Nana Sahib, too, had arrived a month earlier with 300 of his soldiers to support the British. So confident was Wheeler that he even sent two British companies to Lucknow.

But violence erupted in the tinderbox situation within the garrison, and in early June, the sepoys joined the fight. After a nearly three-week-long siege, the outnumbered Europeans surrendered to Nana Sahib and secured a safe passage to Allahabad. But while they were boarding boats at Satichaura Ghat, they were ambushed. The boats were set afire, and those who survived were shot dead on the banks of the Ganges or taken prisoner.

By November 1857, Tope had taken command of the rebel forces. He was known for his very effective guerrilla tactics, which he used to disrupt British supply lines and communications. After the British recaptured Kanpur, Tope went on to lead the rebellion in central India and fought several battles against the British forces.

By March 1858, he moved to Jhansi to aid Lakshmi Bai, who was besieged by British forces.

Also read: Maharaja Bhupinder Singh, patron saint of Patiala peg who used Sikh identity to his advantage

Chase and capture

When Tatya Tope fled Gwalior on 20 June 1858, his army was reduced to a handful of followers. He had no equipment or guns. The British army hounded him from all sides, and kings closed their city gates to him, but whenever he encountered Indian soldiers, he managed to get them on his side.

Pandit Sunderlal gives a vivid account of Tope and his men eluding the British as they crossed the Chambal valley and the Narmada River in his book, British Rule in India. “The first English attempt to check Tatya was made at Jaora Alapur on June 22, 1858,” he wrote. But Tope escaped toward Bharatpur, and immediately, another armed contingent was on his trail. He turned toward Jaipur, where he had supporters, but the British arrived first.

He moved to Tonk, but the Nawab closed the city’s gates and dispatched a troop with four guns. “But the detachment, as soon as it came face to face with Tatya, went over to him with the guns,” wrote Sunderlal. With troops and ammunition, he marched toward Indragarh.

“It was raining heavily. [Colonel] Holmes was rapidly advancing on Tatya’s rear, and General Roberts was leading a force from the Rajputana side to attack him. The river Chambal facing Tatya was in high flood,” writes Sunderlal.

Tope eluded them, and the chase continued until the battle of Kotra, where he was defeated. He had to abandon his guns to escape and crossed the Chambal. This cat-and-mouse chase went on for months, until he crossed the Narmada. Some records claim that he was betrayed by Man Singh, the Raja of Narwar, but Parag Tope writes otherwise.

“The descendants of Man Singh have incorrectly carried on the guilt of his alleged betrayal on their patriotic shoulders for the past 150 years,” he said.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)