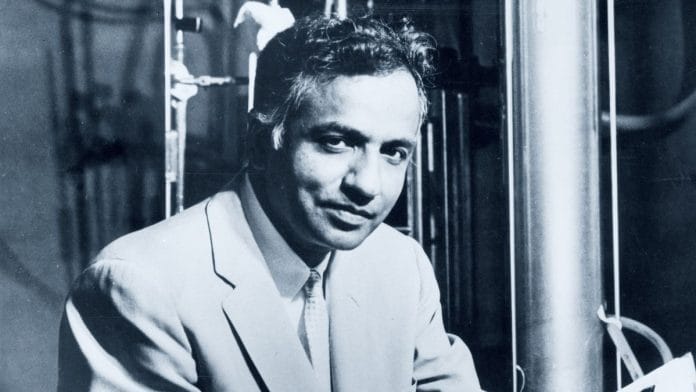

In the early 1980s in Chicago, Nobel Prize-winning theoretical physicist Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar, fondly known as Chandra, received many copies of the gold-plated Bible when he told the world that he was an atheist.

Chandrasekhar may not have been religious, but he followed his own code of rituals and values.

“He was very disciplined. [For years] he would go to Salonika restaurant in Chicago and he would sit exactly at the same window seat for lunch,” recalled astrophysicist Sandip Kumar Chakrabarti, who was his research assistant at the University of Chicago. He is currently director, Indian Centre for Space Physics (ICSP), West Bengal.

To Chakrabarti, Chandrasekhar was more of a mathematician than a physicist. As a “mathematical wizard,” his greatest asset was that he could transform any equation into whichever coordinate system he wanted.

Chandrasekhar was best known for discovering “Chandrasekhar Limit,” the maximum mass beyond which a white dwarf star collapses into a neutron star or a black hole. This breakthrough helped scientists to study the fate of massive stars, and his work later advanced in understanding black holes and stellar dynamics. He was the editor of The Astrophysical Journal from 1952 to 1971, where he made sure top-notch research papers appeared in the journal.

His dedication to astrophysics got him the 1983 Nobel Prize in Physics, and later, NASA named one of its observatories after him.

“His earlier work pertained to the period when there were no calculating machines. He was a good mathematician and expected the same from his students,” said Professor Amar Nath Maheshwari, former Chairperson of the National Council for Teacher Education (NCTE), India, in an email conversation.

Maheshwari, who was doing his doctoral research at the University of Chicago in 1964, first found Chandrasekhar “unapproachable,” but changed his opinion as he got to know him and began working with him more closely.

Chandrasekhar’s manuscripts were a work of calligraphy.

“The derivations are so neat. There’s no cancellation. It’s just the long, huge equations going one after another. It was all inspiring to see somebody who could just derive that kind of stuff from the most complex equations by hand,” said Radhika Ramnath, Chandrasekhar’s niece and the joint secretary of Delhi Council of Child Welfare.

Pushing the limits

In many ways, Chandrasekhar was a reluctant physicist. Mathematics was his first love.

Born in 1910 in Lahore in undivided India, he was deeply driven by his zeal for research. He never wanted to take up physics, but did so on his father’s instruction. He enrolled for a physics programme in Presidency College, Madras in 1930. One month into his bachelor’s programme, he was awarded the government of India scholarship for graduate studies in Cambridge, England.

It was during this long journey by sea that the 19-year-old prodigy started calculating the maximum mass a white dwarf star could theoretically hold—using Einstein’s relativity and the fundamentals of quantum mechanics. The result was named after him, as the now-famous Chandrasekhar Limit.

For the next 10 years, Chandrasekhar studied how stars grow and interact in the vast universe. After his stint at Cambridge, in 1933, Chandrasekhar moved to Trinity College, where he met Arthur Eddington, an English astronomer and physicist, a rival in Chandrasekhar’s life.

Eddington called Chandrasekhar’s work a “stellar buffoonery” and went on to discredit the idea of his stellar limit. “There should be a law of nature to prevent a star from behaving in this absurd way,” Eddington said of Chandrasekhar’s work.

It’s little wonder, then, that the physicist from India felt left out, an interloper among other astronomers.

“He told me that in retrospect, he felt that it was a good thing that happened. If you get fame at such an early age, you don’t know how you deal with it,” said Ramnath.

Chandrasekhar had his own way to move on from academic arguments and fights. “He was told that (his theory) is absurd. But he just wrote a book on it, finished the chapter, and moved on to the next phase,” Ramnath added.

Until now, there have been no direct observations of any star that would exceed the Chandrasekhar Limit. His calculations have helped so far to understand supernovas, neutron stars, and black holes, and extended his knowledge to comprehend a mathematical theory of black holes.

Man beyond the science

Chandrasekhar never held back on his criticism of the Indian government.

“…he felt that a good person in India was not given his due…,” wrote R Nityananda in Current Science Journal published in September 1995. Chandrasekhar was also upset with the growth of hierarchy and bureaucracy in the Indian scientific community.

Despite his disagreement with the government and the Indian scientific establishment, he had his fair share of engagements with the Indian National Science Academy, the Indian Institute of Science (IISc), and Kodaikanal Observatory. In his visits to Bengaluru, he was found eagerly engaging with students and talking to young researchers.

“He loved being asked questions, whether it was scientific or not,” said Ramnath, who had accompanied Chandrasekhar along with other family members to his lectures.

The fact that no one asked him questions bothered Chandrasekhar. “He asked me once why don’t you ask me (any questions)? I said I wouldn’t even know where to start because I don’t know the basic term itself. He said that itself is a question,” Ramnath recalled.

Chandrasekhar did not buy the idea that scientists are driven by a “holy passion” to unlock nature’s secrets. “What actually does give substance and reality to the efforts of a scientist is his desire to participate actively in the progress of his science to the best of his ability,” writes Chandrasekhar in his book Truth and Beauty: Aesthetics and Motivations in Science.

His way of contributing to the progress of science was through research. And lots of reading. “He had books up to the roof and had this little ladder which he used to climb to take up whatever he wanted,” Ramnath recalled from her visit to Chandrasekhar’s place in Chicago.

On 21 August 1995, Chandrasekhar felt unwell and drove himself to the University of Chicago Hospital, where another cardiac arrest took his life.

Chandrasekhar did not fear death. His only worry was that the knowledge in his head would die with him, said Ramnath.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)