New Delhi: Communal riots broke out in Hyderabad’s Yakutpura in the early 1980s. Chaos gripped the streets as people ran in all directions. Amid the confusion, a tall man in a sherwani rode in on a motorcycle, cut through the mob, went first to the Muslim basti, and then straight into the Hindu basti.

People shouted, “Oh, Salar is here, Salar is here.”

He commanded the Muslims to return to their homes, and the Hindus, seeing him, went back into theirs. No guards, no police—only one man stood, that was Sultan Salahuddin Owaisi.

“Sultan Salahuddin Owaisi was a leader of the people. He always lived among them,” recalled Aktarul Wasey (74), Professor of Islamic Studies, Jamia Millia Islamia, and a close friend of Salahuddin Owaisi since 1969.

Born on 14 February 1931 in Hyderabad, Salahuddin Owaisi revived the All India Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen (AIMIM) and firmly established it as a major force in India’s electoral politics. Although AIMIM itself could not expand outside Hyderabad’s old city, Salahuddin Owaisi emerged as a leader of the Muslim community in India. By the 1970s, he had redefined MIM as a strong political organisation by balancing advocacy for minority rights with pragmatic compromises. During times of communal tension, his leadership stabilised the Majlis and established it as a family-based party that would influence politics for decades.

Salahuddin Owaisi received the title Salar-e-Millat (commander of the community), an honour bestowed by the public. People of Hyderabad fondly call him Salar.

Syed Ahmed Pasha Quadri (70), AIMIM general secretary and a party member since the age of 20, is undergoing dialysis today. But that doesn’t stop him from remembering his old friend Salar.

“People used to record his speech and play it. He (Salahuddin) had a lot of love for the public. I have never seen such a person in my life,” he said.

Yusuf Pathan, a PhD scholar from Toronto, explained that Salahuddin’s early connection with people fueled his rise. His growing network of supporters and sympathizers helped him tackle challenges.

“His connection with the people from the initial stages greatly helped his rise. He had a continuously expanding network of supporters and sympathisers, which helped him in the face of challenges from rebel party members,” Pathan added.

‘Darling of Muslims’

India’s official history shows a trend of neglecting Dalit, Muslim, and Adivasi leaders. Leaders from marginalised communities often lack archives or documented data, leaving only oral memories and stories. Salahuddin is no exception. Very little has been written about him in newspapers, books, or research, and online searches show only a few videos.

People recount Salahuddin’s stories like an action film. For them, he was nothing less than a macho hero.

In 2007, a researcher from a Hyderabad local NGO, Shefali Jha, met Salahuddin for the first time at the ‘Darussalam’ headquarters of the AIMIM. She had gone there for research work. Salahuddin had no security around him.

“Ji amma kahiya,” he said to her. (Yes, mother, please say.)

Recalling this, Jha said, laughing, “No one had ever called me ‘amma’ before. Who calls whom ‘amma’ like this?”

Despite this being her first meeting with Salahuddin, he inspired her to pursue a PhD on MIM and minority politics.

“He had an aura about him. He was fearless and outspoken. He never hesitated to say what he felt,” Jha said.

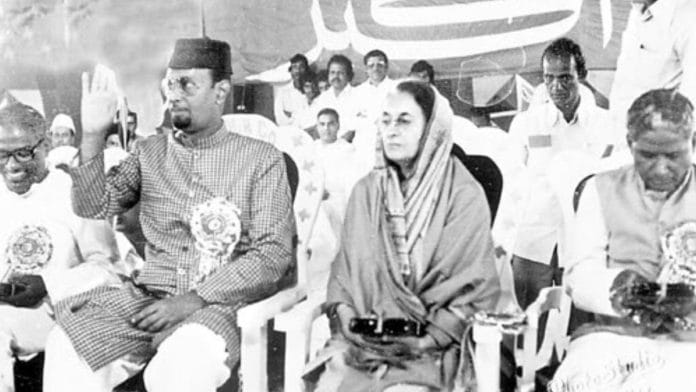

Political Scientist and author Munir Ahmad Khan wrote about Salahuddin in his thesis, which he submitted to Osmania University in 1975: “Basking in the glories of constant electoral victories, he has repeatedly defeated ministers and tough politicians. Tall, immaculately dressed, with a deep husky voice and undaunted posture, he has become the darling of the Muslim masses. Though he does not possess his father’s oratory skills, he can always arouse a crowd.”

Salahuddin Owaisi trained his three sons—Asaduddin Owaisi, Akbaruddin Owaisi, and Burhanuddin Owaisi—in politics from an early age, following the family tradition. Critics often target the party for being dominated by a single family.

Early AIMIM

Salahuddin began his political career at the age of 24 by winning the 1960 Hyderabad Corporation election from Mallepally. He later won Assembly elections from Pathergatti (1962), Yakutpura (1967), Pathergatti again (1972), and Charminar (1978 with 51.98 per cent vote share and 1983 with 64.05 per cent).

He entered Parliament in 1984, winning Hyderabad with 38.13 per cent of the votes. He retained the seat in 1989, 1991, 1996, 1998, and 1999, serving six consecutive terms until 2004.

According to Yusuf Pathan, Salahuddin quickly proved his mettle as Opposition Leader in the Municipal Corporation of Hyderabad. He faced immense challenges from both inside and outside the community for boldly entering the political arena.

“Majlis’ entry into electoral politics was viewed with distrust by both the Congress and Jan Sangh. The then-existing Muslim political and intellectual class also discouraged the emergence of a party openly advocating the rights of the Muslim community,” Pathan told ThePrint.

According to Salahuddin, electoral politics is where the Indian Muslims can demonstrate their demands strategically. Parties with even a few seats can play a major role in the era of alliances. They were successful in it in the erstwhile Andhra Pradesh and Telangana as they navigated successive governments of Congress and Telugu Desam Party (TDP).

‘Sole representative party of Muslims’

In a video, Salahuddin, wearing a grey sherwani and a black skull cap, is seen addressing a gathering. Beside him sat his eldest son, young Asaduddin Owaisi. Salahuddin fixed the mic and, in his firm tone, said: “AIMIM buchchon ka khel nahi hai.” (AIMIM is not a child’s play.)

Sultan Salahuddin Owaisi asserted that Muslims should not remain shackled to any party but should carve out their own path in alliance with Dalits and other communities who have been left behind. He called it an alliance of the oppressed.

“Salahuddin Owaisi demonstrated that Indian Muslims have a space within the democratic setup to voice their concerns and gain their fair share. He was convinced that they were shortchanged by the established parties and therefore the need for AIMIM,” said Pathan.

In his speeches, Salahuddin clearly expressed concern over rising communalism. He said that Muslims were being systematically marginalised.

“Riots are instigated in places where Muslims are somewhat financially stable. By creating riots there, your finances and businesses are destroyed,” he claimed in a speech in 1990.

Salahuddin criticised the Atal Bihari Vajpayee government, saying its policies sought power by pushing a uniform civil code and revoking Article 370.

In Parliament, he added that after the government came to power, statements from groups like the Vishwa Hindu Parishad and Bajrang Dal surged, while the government struggled to maintain control. He accused it of creating unrest for minorities, depriving them of rights, exploiting their money and labour, and neglecting education and welfare.

According to Jha, Salahuddin’s first big achievement was control of Darussalam for the party, re-establishing the MIM’s claim as ‘Musalmano ki waḥid numainda jamaat’ (the sole representative party of Muslims).

His second was recognising the limits of a political system that demanded Muslims be model secular citizens while branding them as a threatening, ‘anti-national’ minority.

During a protest against ‘miscreant activities’ near a mosque in the early 1970s, Salahuddin and Syed Ahmed Pasha Quadri, general secretary of AIMIM, were arrested and sent to jail.

“We spent a lot of time together in jail. It was a good time. He faced many cases,” Quadri told ThePrint.

He claimed that the Congress government at the time often tried to weaken the Majlis by using ministers and chief ministers against it. Congress leader Dr. Chinna Reddy even declared in the assembly that he had come to finish the Majlis.

“They used to compete with him (Salar). Salar would make their (opposition) speeches (promises or statements) fail. We have defeated them (opposition) every time.”

Politics changes with time

In times of distrust, people test a leader’s loyalty to his promises. This is a story every child in the city knows. In the 1960s, Salahuddin was in the middle of his wedding rituals in old Hyderabad when he heard of a communal riot nearby. Leaving the ceremonies, he mounted his bike and rushed to the scene. A group of young men, who had spread false news to see if he would intervene on his wedding day, were stunned to see him.

Salahuddin kept his politics focused on local and civic issues.

After the Emergency, the Majlis had a reputation for street violence and was widely seen as a party of goons. Salahuddin understood this clearly and acted accordingly. He became “notorious” for his street politics, according to Jha.

“As a leader of a minority, he recognised in a very clear way the challenges that Muslims would face in India. Because he had seen the experiences of 1947 and after that. It was always a thing that he kept in mind. How to represent and fight for the Muslim interest,” Jha added.

In the new neoliberal post-1989 system, which emphasised a business-friendly environment and curbed violence, Majlis under Salahuddin actively raised civic issues—roads, water, and city infrastructure—while also positioning itself as a party of the city.

Salahuddin worked for the economic and educational uplift of minorities by establishing engineering, medical, pharmacy, management, and nursing colleges, an ITI, two hospitals, a co-operative bank, and the Urdu newspaper Etemaad, while promoting the Urdu language, literature, and culture.

Also read: Babri to n-bomb, Atal Bihari Vajpayee was a man of twists and turns

Limited to Hyderabad

Jha said that North India and Hyderabad had different histories and political idioms. This became Majlis’s strength—it survived by staying rooted locally and maintaining working ties with state governments, a strategy that wouldn’t have worked at the Centre.

“Salahuddin chose to stay local,” she added.

The absence of the internet and social media was also a reason. But after Akbaruddin Owaisi’s controversial speech— “If the police were removed for 15 minutes, India’s 25 crore Muslims (officially 13.8 crore) would teach a lesson to 100 crore ‘Hindustanis’”— went viral, AIMIM got a chance to expand. Asaduddin Owaisi strengthened the party’s roots across the country by boldly raising contemporary minority issues.

According to Fazil Hussain Parvez, editor of Gawah Magazine, Muslims across India connect with Asaduddin Owaisi and the issues he raises. But he still hasn’t matched the aura and stature of his father.

He added that people may have disagreed with Salahuddin, but despite their opposition, they still voted for him. That is why, even after his passing on 29 September 2008, thousands flock to Salahuddin’s dargah in Aghapura to pay respects and offer chadars.

“Hyderabad and its politics still deeply feel the absence of Salar-e-Millat,” Parvez said.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)