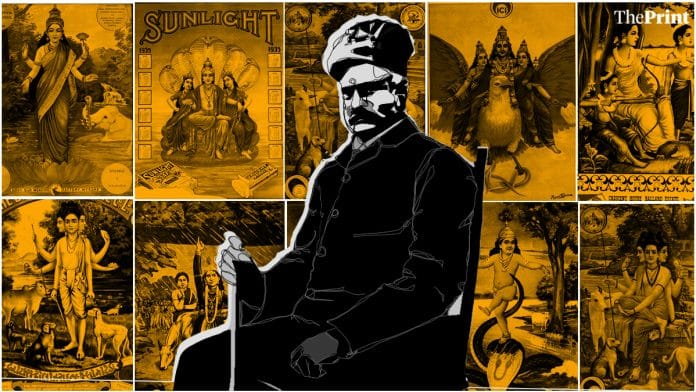

New Delhi: From the second half of the 19th century, Indian temples, streets, shops and homes were slowly inundated with colourful prints of deities and mythological figures — many of which could be traced back to the paintings of Raja Ravi Varma. Encouraged by the British to use western artistic techniques to reinterpret Indian mythology, Varma set in motion the creation of an Indian aesthetic that exists till date.

On his 113th death anniversary, ThePrint takes a look at his life, artistic practice and his unending legacy.

Traditionalist and modernist

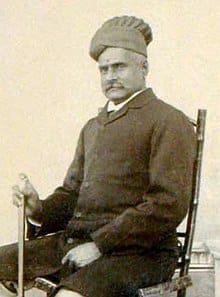

Varma was born on 29 April 1848, in the village of Kilimanoor in Kerala to a family of chieftains known as the Koil Thampurans. His community was close to the royals of Travancore as bridegrooms for the princesses were always taken from the Thampuran family.

Varma was eager to paint from a young age, and his uncle encouraged this artistic inclination, persuading the Maharaja of Travancore to let him stay in the palace and learn from famous artists who visited the court. One Englishman, Theodore Jensen, was commissioned by the Maharaja to paint a series of royal portraits in 1863. Varma took this opportunity to observe and absorb all that he could from Jensen and thus began his foray into oil painting and European realism.

Art historian Geeta Kapur describes Varma as both a traditionalist and modernist. He grew up studying Sanskrit and orthodox scriptures, but took pleasure in experimenting with European drawing styles, exploring realism and using his scientific knowledge of perspective in landscapes and portraits.

He adapted western styles to an Indian context and developed a potent Indian visual aesthetic. In her book of essays When Was Modernism (2000), Kapur writes that it would be incorrect to reduce Varma’s work as cheap imitation of European techniques since he was a self-taught “gentleman artist in the Victorian mould” who was also “a nationalist charged with the ambition to devise a pan-Indian vision for his people”.

His work in realism began as a portrait artist of mostly aristocratic women. He then delved into mythological paintings inspired by Puranic texts, and later narrative paintings after being influenced by Parsi and Marathi theatre in Bombay.

Regarded as a part of India’s nation-building project, Kapur recalls how Indian economist Asok Mitra had once said that Varma’s work helped in “recounting the ancient Indian ideal of healthy beauty and enjoyment of life”.

Thus, Varma came to be known as the “father of modern Indian art”.

Also read: Charminar — the ‘rugged’ cigarettes that promoted toxic masculinity

From a royal painter to an accessible and affordable artist

As Varma became successful, his patrons included members of aristocratic families and royals of both Indian and foreign descent. He even befriended the likes of Congress leader Dadabhai Naoroji, writes Kapur.

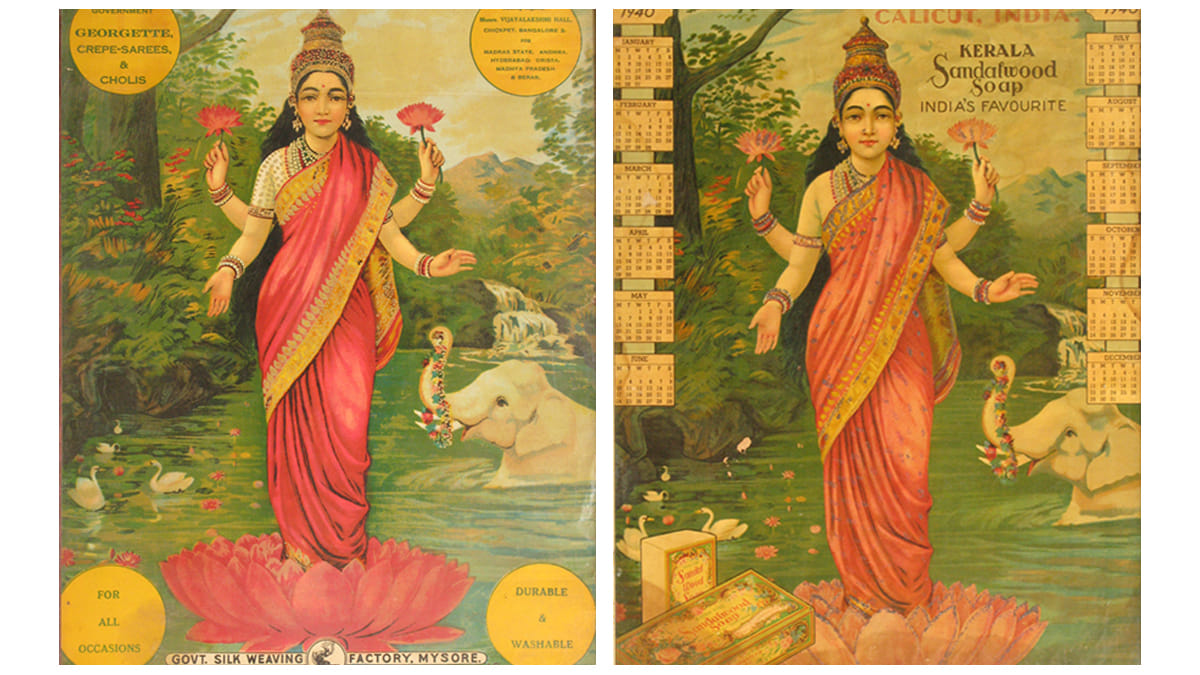

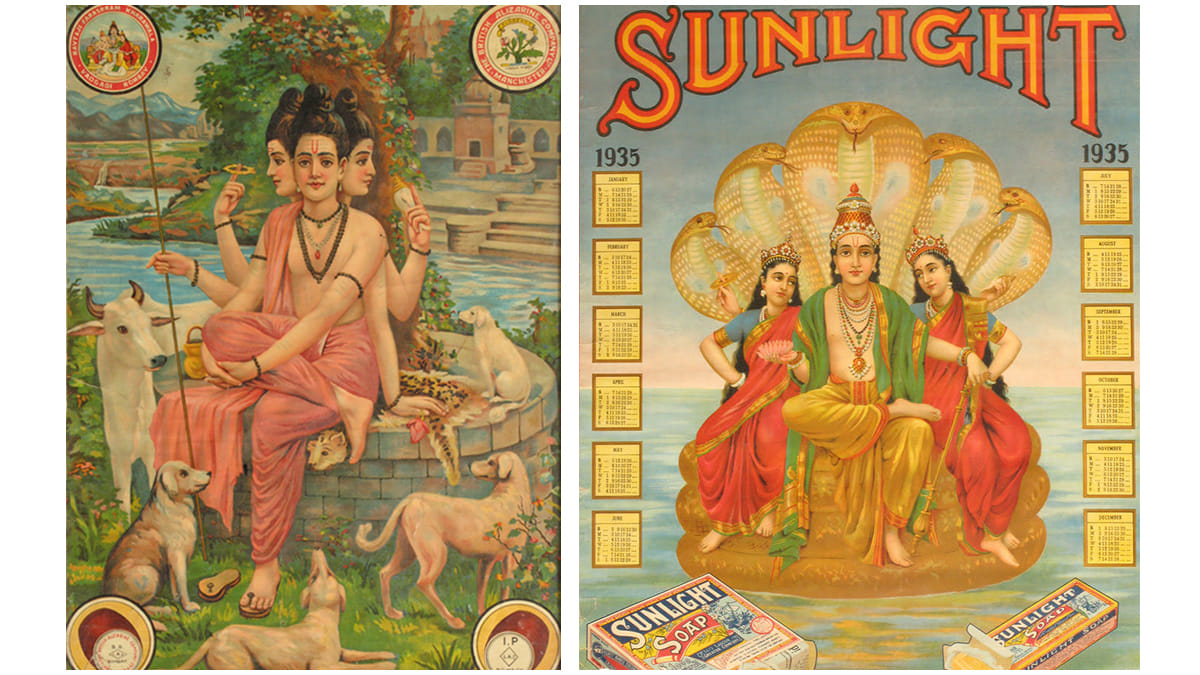

The ubiquity of Varma’s work, however, came to light only after it started getting mass-produced and became more accessible to the middle class in the form of oleographs — prints textured to resemble oil paintings.

As author Kajri Jain points out in her essay India Bazaar, paintings were earlier sent to Germany and Austria to be lithographed (a print technique that uses metal plates along with water and oil). But on the advice of his brother C. Raja Raja Varma and Sir Madhava Rao, the diwan of Travancore, Varma set up his own printing press in Maharashtra — first in Ghatkopar and eventually in Lonavala in 1894.

The lithographic press was set-up with the help of a German technician, and soon after, presses in other parts of the country like Poona (now Pune) and Calcutta (now Kolkata), and the famous Sivakasi press in South India started to emerge. The mythological, religious and secular images supplied by these presses to the entire country led to, what Jain calls, a ‘bazaar economy’ — an informal network that ran parallel to state-led corporate economy of English-speaking elite which persisted even after Independence in 1947.

By mass-producing oleographs, of which the most popular were images of Hindu gods and goddesses, Varma’s printing press challenged narrow ideas of the ownership of art. Caste hierarchies in Hinduism had dictated who could own images of gods, and where and how these images must be displayed.

Completely shattering the idea of ‘high and low art’, the ‘royal’ artist became a champion of making art accessible to all. His images inhabited all sorts of spaces and were transposed to all sorts of forms including in calendars, packaging, street signs, book covers and movie posters.

Michelle Cheripka, in her essay The Lives of the Hindu Gods in Popular Prints: The Ownership of Imagery, notes that by providing equal access to these images, Varma was challenging caste and class hierarchies as the circulation of these images broke down the idea that they were meant to rest solely within temples or in private collections.

Varma, hence, gave birth to secular-sacred images that can even today can be found in puja rooms, calendar advertisements, tiles in public spaces, flex banners and all kinds of packaging for products ranging from soap to incense. As JNU professor Shukla Sawant explained to Michelle Cheripka, “The images are the same, but they have different lives.”

Varma’s legacy as one of India’s most revered artists lives on through academic discourse, cinema dedicated to his life and Kilimanoor Palace — an estate in his birthplace that now houses many of his works and is a famous tourist spot in Kerala.

But his most tangible contribution to our everyday visual culture is his contribution to bazaar art, which more modern printing presses like New Delhi’s Brijabasi Art Press continue to keep alive.

Also read: What unfolded when Gandhi met a playwright, a fascist, a comic legend, a Nobel laureate