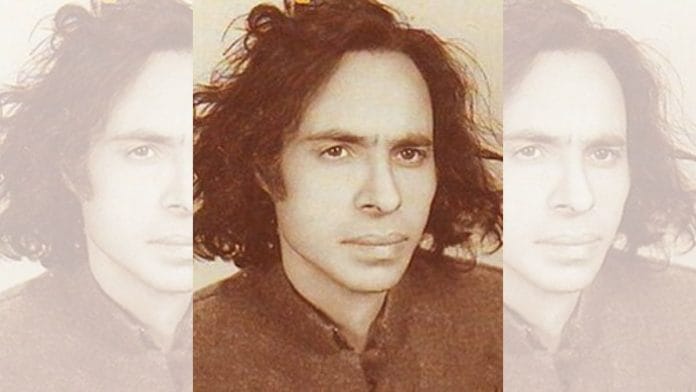

It took Jaun Elia’s death on 8 November 2002 for the world to fall in love with his poetry. Today, he is one of the most Googled poets, but still remains an enigmatic figure in modern Urdu poetry—a Pakistani Marxist, an atheist, and most importantly, a man who questioned the status quo.

But for all the hype around his verse, Elia is often reduced to a tragic poet. Love and loss are central themes in his work; his verse is intense and raw. But they represent only one facet of a complex, multi-dimensional poet whose life was marked by intellectual rebellion and political activism.

“Jaun Elia, in my view, is one of the most misunderstood writers in the subcontinent. He is often portrayed as a ‘heartbroken poet’ who went insane after separation from his wife,” Indian historian Saquib Salim told ThePrint. He admitted that YouTube videos showing Elia reciting poetry at mushairas (poetic symposiums) in a distinct style further cemented this stereotype. “But it’s important that we reassess Jaun Elia as a thinker, philosopher, political commentator, and socialist.”

This one-dimensional characterisation, Salim argued, is a distortion of Elia’s true identity as a committed Marxist who was deeply involved in politics and social issues. His lakhs of followers online and young poets who see themselves as the next Elia often fail to grasp one key fact.

“His writings (poetry as well as prose) are full of communist messages,” said Salim.

The rebel poet

Many critics and poetry enthusiasts see Elia as someone who challenged the notions of traditional Urdu poetry.

“I grew up with Elia’s poetry. It taught me to embrace vulnerability and the raw, unfiltered aspects of human emotion from a young age,” said poet and Elia’s official English translator in Pakistan, Ammar Aziz.

“His themes of alienation and what I call existential otherness have significantly shaped my approach to writing English ghazals.”

Jaun Elia’s first poetry collection, Shayad (perhaps), was published only in 1991. Despite the delay in its release, the collection catapulted him to popularity, especially in mushairas, both in Pakistan and abroad. This late recognition may explain why he came to be seen primarily as a poet of mushairas, a label that overshadowed his literary contributions.

Even literary critics, for a long time, failed to give his work the attention it deserved, Pakistani translator Raza Naeem wrote in his tribute for Elia. Yet his presence at mushairas, where he often performed with theatrical flourish, captivated audiences. His recitations were known for their intensity, with Elia sometimes turning his back to the audience as an act of contempt.

His cultural impact has only grown with time, and it’s not uncommon for people on both sides of the border to quote Elia’s work. In August this year, members of the People’s Democratic Party in Jammu and Kashmir expressed their frustration through Elia’s poetry after they were denied tickets for the Assembly elections.

“Waffa, ikhlas, kurbani, Mohbat, ab in lafzou ka peecha kyu karay hum (loyalty, sincerity, sacrifice, love, why should anyone chase these words now?),” Aijaz Ahmad Mir, former PDP MLA, wrote on X, quoting from one of Elia’s poems.

Also read: Mir Taqi Mir wasn’t a poet of longing like Ghalib. He lived in the resistance space

Turbulent life

Before Jaun Elia became a ‘through and through Karachiite’, his home was Amroha in Uttar Pradesh. Born Syed Sibt-e-Asghar Naqvi in 1931, Elia later adopted his father’s surname and moved to Pakistan after Partition. Both his brothers, Rais Amrohvi and Syed Muhammad Taqi, were well-known scholars in literary circles.

Elia was initially opposed to Partition but eventually relocated to Karachi in 1957, where he spent the remainder of his life working as a journalist and translator.

While many of his contemporaries embraced Pakistan’s identity as an Islamic state, Elia’s Marxist leanings made him disillusioned with the country’s ideological foundations. “If Pakistan was formed in the name of Islam, then at least the Communist Party would never have supported its demand,” he wrote in Shayad.

In one of his poems, Sarzameen-e-khwab-o-khayal (Land of Dreams and Imagination), Elia envisions a revolution that would reshape Pakistan through communist ideals. “Khush badan! Perahan ho surkh tera, Dilbara! Baankpan ho surkh tera.” (O beauty! Here’s hoping your apparel is coloured red, beloved! Here’s hoping your adolescence is coloured red).

Elia’s poetic voice, however, was not one of surrender. Instead, his poems convey a relentless search for new meanings, even in despair. This was perhaps why many viewed him as ‘the defeatist who won us over’.

Despite his intellectual rigour and political activism, Elia’s personal life was marked by turmoil. His marriage to the renowned feminist, Zahida Hina, ended in divorce in 1992, deepening the themes of loss and alienation that permeated his work.

In 2021, his daughter Fainaana Farnaam wrote an open letter in The Express Tribune about her turbulent childhood and her father’s alcoholism.

“I don’t understand how people never understood that while Jaun Elia is their favourite poet, he is my father. I could not search for life in his verses, He was my life. We needed our father Jaun Elia, not the poet, and our father was lost somewhere,” she wrote.

(Edited by Aamaan Alam Khan)

Pakistani and atheist and marxist. He is an idol for every woke Indian. Angst ridden with a destroyed family life who made his children unhappy. Even better. Muslim roots and atheism is best of both. And he can drink because he is Marxist. Yet claim Islam is better

What is with this pakistan fixation of fake news peddler couptaji ?

No one cares for a failed poetry of a failed country.

Hve you done any articles on poets of south india ? How is pakistan more imortant to you than india ?

Shame on you . It is indians who pay for yur news. Not some jihadis from pakistan